Somewhere Over the Rainbow......

Yggdrasil and the Nine Worlds

[Introduction][Main Menu][Home]

[Poetic Edda][Snorri's Edda][Scholarly View][World-Mill][Symbolism]

at the Bottom of the Sea

The Meginwerk of the Ancient Germanic Cosmos

The Grotto-songr and The Tale of Froði's Mill

EVIDENCE FOR THE EXISTENCE

OF A COSMIC MILL IN GERMANIC MYTHOLOGY

An Excerpt from

THE MILL IN NORSE AND FINNISH MYTHOLOGY

BY CLIVE TOLLEY

Saga-Book for the Viking Society of Northern Research, no. 24, 1995

|

THE MILK ocean is churned, in

Indian myth, with an outlier of the world mountain to

produce the soma of immortality, as well as a host of other

guarantors of the world’s fertility and well-being, such as

the sun and moon, along with destructive forces such as the

poison Kal– aku–ta˘ and the goddess of misfortune. No myth

relating anything precisely comparable to this striking

event appears to exist in Norse, yet the image of a cosmic

mill, ambivalently churning out well-being or disaster, may

be recognised in certain fragmentary myths.

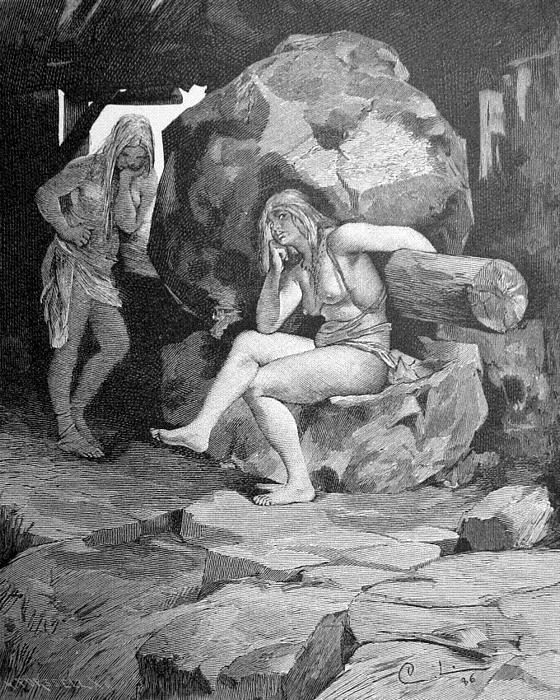

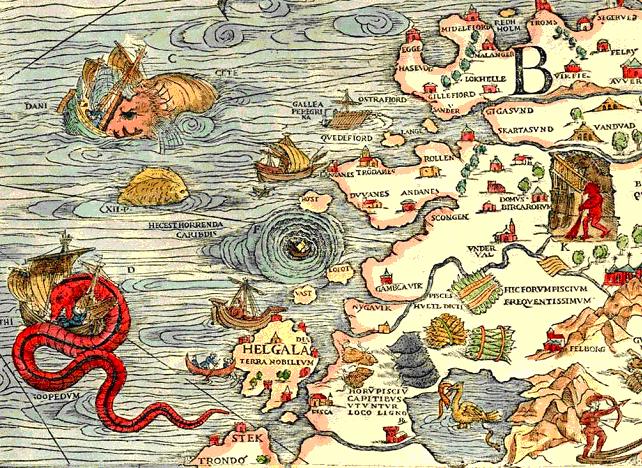

Grotti in Grottasøngr and Snorri’s Edda The myth of the mill Grotti is told by Snorri in Skáldskaparmál (SnE 135–38) and in the poem Grottasøngr, which he quotes. The elements of the myth may be summarised thus: The Mill of Wealth King Fróði of Denmark is renowned for his peace and his wealth (SnE). He buys two strong slave girls Fenja and Menja (Grs) from Sweden (SnE). The quernstones that are to form Grotti are found in Denmark and are given to Fróði by a man with a giant’s name (Hengikjøptr) (SnE). In Grs 10–12 Fenja and Menja claim to have discovered these millstones long ago. They caused earthquakes when they dislodged the stones from the earth. Grotti would produce whatever the grinder bade. No one but Fenja and Menja was strong enough to turn it. Fróði made the giantesses grind gold, peace and prosperity. He granted them almost no rest. They sang Grottasøngr as they worked. Furious at Fróði’s cruelty to them they ground out an army, and a sea-king Mýsingr came and slew Fróði (SnE); in Grs there is merely a foretelling of Fróði’s overthrow. The quern breaks, and the milling must stop (Grs). The end of Fróði’s reign is marked by thunderings and lightnings, earthquakes, the disappearance of the sun, and the upsetting of prognostications (Skjöldunga saga only, see Danakonunga søgur 1982, 39–40). Thus Fróði’s peace came to an end. The Salt Mill Mýsingr takes Grotti, Fenja and Menja. He bids them grind salt. They grind until the excess of salt sinks the ship. This causes the sea’s saltiness. The Whirlpool Mill There is now a whirlpool where the sea fell into the eye of the quern. Comparable are traditions about the Mælström, which was regarded as a ‘grinder of ships’, if not a mill (see below). Of the three motifs, the poem contains only the first; the salt mill and the whirlpool mill may be later additions of common folk tales to the myth. However, the poem focuses on the demise of Fróði after the cracking of the stone, and may have excluded these elements deliberately. The Mælström Purportedly factual reports of the Mælström, the whirlpool off Lofoten in northern Norway, lie very close to the more imaginative concept of a mill in the depths, grinding everything in its stones, and causing a whirlpool with its circular motion, such as is found in the myth of Grotti. Traditions about this real whirlpool may reflect beliefs about Grotti; it is difficult to ascertain whether the myth of Grotti has influenced the picture of the Mælström, or conversely whether the traditions about the Mælström have influenced the depiction of Grotti. The Mælström is first mentioned in the eighth century by Paulus Diaconus (1878, 55–56); he sites the ‘navel of the ocean’ near the Scritobini (northern Lapps), i. e. ‘on the edge of the world’, like Grotti in Snæbjörn (see below), and says that the whirlpool sucks in and regurgitates the currents twice in a day, and ships are pulled down as fast as arrows, then cast back out again just as fast. A similar description is given by Olaus Magnus (1555, 67), who notes that any ships returned from the eddy were whittled down by rocks. The cause of the phenomenon is assigned to a spirit bursting forth capriciously. Schönneböl (Storm 1895, 191) gives a similar report in 1591:17 But I am told by reliable people that there must be some sharp rocks concealed out in that same current, since it flows so terribly strongly, and everything that enters that current must go entirely under and to the bottom.  Snæbjörn’s Verse on Grotti A lausavísa attributed to a certain Snæbjörn, perhaps, as Gollancz (1898, xvii) suggests, to be identified with Snæbjörn Hólmsteinsson, an Arctic adventurer of the late tenth century mentioned in Landnámabók (1968, 190–95), alludes to a mighty water-mill turned by nine women (Skj B I 201):

‘The nine brides of the island quern-frame’ are the waves of the ocean (the daughters of Ægir); lúðr is the frame of a hand-mill; —that which frames islands is the sea (cf. eyja hringr, ‘ring of [i. e. around] islands’, in the same sense) (Meissner 1921, 94); the same sense is found in jarðar skaut, ‘rim of the earth’, i. e. the sea, but in this case there is the additional implication of the action taking place ‘out at the edge of the world’ where, it is to be surmised, the mythological ocean mill was to be encountered. Alternatively or additionally, lúðr could stand for the whole mill; that which grinds up islands is, again, the sea. Snæbjörn makes his picture of the terrible (and supposedly real) whirlpool vivid by using the metaphor of the mill, identified by metonymy with the mythical Grotti. Grotta hergrimmastan skerja appears to identify Grotti as the grinder of the skerries: ‘The most army-cruel Grotti [= mill, grinder] of skerries’. Grotta skerja, ‘mill of skerries’, would then be parallel to eylúðr, ‘mill of islands’, if lúðr is taken as a synecdoche for ‘mill’. The ‘mill’ which grinds up skerries, or at least is sited there, is a whirlpool (cf. the Mælström). An allusion to the ‘grinding out’ by Grotti of the army which destroyed Fróði is also clear.

Líðmeldr Amlóða, ‘the meal of the liquor of Amlóði’. ‘The liquor of Amlóði’ (líð Amlóða) must refer to the sea, the meal of which is sand. The details of Amlóði’s connexion with the sea are now lost to us; that such a connexion existed however is witnessed by Saxo; Prince Amlethus, feigning madness, is walking with some companions along the beach (Saxo Grammaticus 1931, I 79 (III:vi:10)): Arenarum quoque præteritis clivis, sabulam perinde ac farra aspicere jussus, eadem albicantibus maris procellis permolita esse respondit. Also, as they pass the sand-dunes they bid him look at the meal, meaning the sand; he replies that it has been ground small by the white tempests of the ocean. Krause (1969, 94) proposes that Amlóði began as a personification of the irrational tossing sea, which is suggested by his etymology of the name.

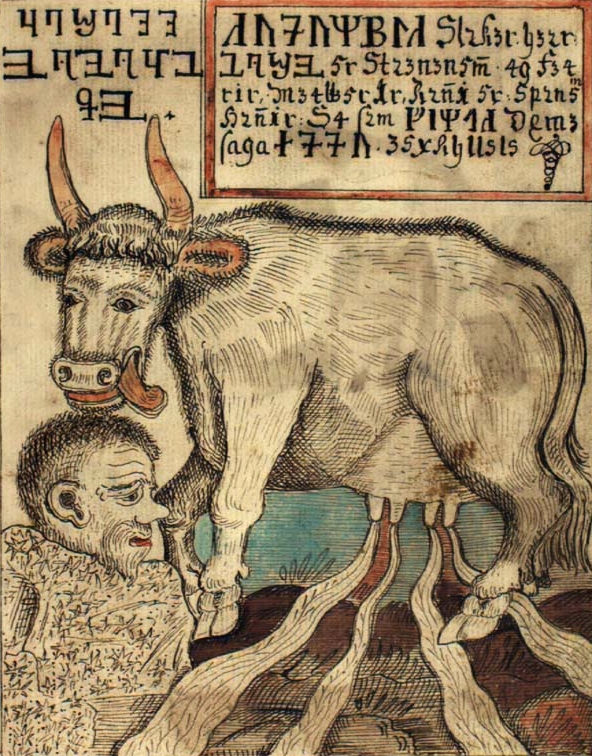

Bergelmir

In answer to Óðinn’s question, who was the oldest of the Æsir or of Ymir’s descendants, the giant Vafþrúðnir replies that before the world was made, Bergelmir was born, son of Þrúðgelmir and grandson of Aurgelmir (Vm 29). He repeats the first half of his reply in Vm 35 in answer to the question of what he first remembered, and continues with more information on Bergelmir:

The earliest interpretation of this myth is the one offered by Snorri (SnE 14):

From Snorri’s statements that the frost giants were drowned in Ymir’s blood, and that Bergelmir and his family were the only ones to escape to re-establish the frost giants, it is evident that he is identifying Bergelmir’s situation with that of Noah (Genesis 6–8), and probably relying on apocryphal accounts of the survival of the giants after the Flood (Og took refuge on the roof of Noah’s ark in Rabbinic tradition). Such tales were known in Anglo-Saxon England and early medieval Ireland (James 1920, 40–41; Carney 1955, 102–14). In accordance with his interpretation of Bergelmir’s situation, Snorri refers to the lúðr (‘mill frame’) as if it was already a possession of the giant (it is sinn, ‘his’), into which he and his family could step, as if into a sea vessel which could surmount the waves of blood. In following this tradition, Snorri has ignored the text of Vm 35, which states that Bergelmir ‘was laid on a lúðr’. Snorri’s tale of Bergelmir therefore does not go far towards explaining the myth of Vm. The word lúðr has, rather unnecessarily, given rise to a good many interpretations bearing at most a tenuous relation to the recorded meaning of the word in Old Norse, namely ‘mill-frame’. If Bergelmir was placed on a mill-frame, he was clearly ground up: Rydberg (1886, I 431–32) long ago suggested that after the world was formed from the body of the first giant Ymir the act of creation continued with the milling up of Bergelmir to produce the soil and sand of the beaches (cf. the sand described as ‘meal’ by the companions of Amlethus in the citation from Saxo above); equally, Bergelmir might represent an alternative mode of creation, syncretised genealogically by making him the grandson of Aurgelmir (who is produced from the primeval waters and then engenders the race of giants according to Vm 31). The name Bergelmir designates the third of a generation of giants with names formed with the element -gelmir (cf. gjalla, ‘roar’) mentioned in Vm 29. Aurgelmir is either ‘mud roarer’ or ‘ear [of corn] roarer’. Þrúðgelmir is ‘power roarer’. Bergelmir appears to be ‘barley roarer’; this would fit naturally with the theme of grinding (cf. Byggvir below). The element -gelmir connects these names with waters. In Rm 4 the underworld river Vaðgelmir, ‘ford roarer’, is mentioned; and the primeval source of all rivers, existing before the creation of the world, was Hvergelmir, ‘cauldron roarer’. Gelmir is linked etymologically with Gjöll, the river round the underworld (AR §577). A primordial oceanic connexion and an underworld river connexion are thus implied for the giants of Vm (as noted by de Vries, AR §577), which is in line with the chthonic powers later associated with giants; more strikingly the names betray their origin as names of roaring waters. A connexion with fertility is also apparent. In Aurgelmir, aur- is either the fertile mud with which the world tree is sprinkled in Vsp,31 or an ear of corn; in Þrúðgelmir, þrúðr, ‘power’, derives from þróa, ‘thrive’; in Bergelmir, ber- is probably ‘barley’, and the verse calls him specifically fróðr, which can mean ‘fertile’ as well as ‘wise’. If the term lúðr is accepted as ‘mill’, then Bergelmir may emerge as a being who furthers the fecundity of the earth through being ground up in a mill. Such a mythological motif is not unique; a tenth-century survey of Muslim culture tells us the following about the fertility god Tammu–z, worshipped among the pagans of Haran (Al-Nadim 1970, 758): Tammu–z (July). In the middle of the month there is the Feast of al-Bu–-qa–t, that is, of the weeping women. It is the Ta–-u–z, a feast celebrated for the god Ta–-u–z [i. e. Tammu–z]. The women weep for him because his master slew him by grinding his bones under a millstone and winnowing them in the wind. Presumably related to this is the much more ancient Ugaritic myth of the contest of Baal (a fertility god like Tammu–z) and Môt, in which Môt is ground up, apparently in an act of bestowing fertility on the land (Gordon 1949, 47: Môt cries out ‘Because of thee, O Baal, I have experienced . . .grinding in the mill-stones’). In Norse too there is found the idea of a divinity, and moreover a divinity of barley, being ground: in Ls 44 Loki says to Byggvir (a nomen agentis from bygg, ‘barley’): at eyrom Freys mundu æ vera ok und kvernom klaka, ‘you shall ever be at Freyr’s ears and twitter beneath the quern’. Since Byggvir is the god of barley,which is the basic ingredient of ale, the reference here is clearly to the grinding of the grain in the brewing process. Thus in the reference to Bergelmir being laid on the lúðr may possibly lie an allusion to a cosmic mill, associated with water. The Indian churning of the Milk Sea would present a parallel instance of the fertile ‘milling’ of water. Mundilfoeri The image of a cosmic mill may lie behind Vm 23:32:

The commonly accepted translation of hverfa as ‘traverse’ is unacceptable, since the use of hverfa without a preposition in this sense would be unparalleled; the meaning must be transitive ‘turn’. We may note that in Vsp 5:1–4 the sun moves her hand purposefully. The name Mundilfoeri occurs only here and in SnE 17–18 (based on this stanza). The majority reading of the manuscripts is -foeri. Related to foera, ‘move, carry’, -foeri could signify ‘mover, carrier’, or ‘device, instrument, equipment designed for a special purpose’ (see Fritzner 1886–96, s. v. foeri 3); or as a weak adjective, ‘effective, capable’. Mundil- may be related to mund, ‘hand’, or mund, ‘time’; there may even be a play on both senses, accounting for the uniqueness of the name. Cleasby and Vigfusson (1957, s. v. Mundil-föri ) suggest that the name is ‘akin to möndull [mill-handle], referring to the veering round or revolution of the heavens’. If Cleasby and Vigfusson are right, the name Mundilfoeri has been designed to signify the mill-like device that turns the heavens by means of a ‘handle’. Sun and Moon are, according to this genealogical fiction, his children who operate the device for him or by means of him. This turning of the cosmos, pictured as a mill, is the diurnal and yearly movement of the heavens. In the Indian myth of the Milk Sea, the sun and moon arise as a result of the churning of the milk ocean, just as in Norse they are the children of the turner of the cosmos. A very similar image to that suggested for the Mundilfoeri myth occurs in a Mordvin mythological poem (text and German translation in Ahlqvist 1861, 133–34). Here, the sun, moon and stars are said to be on the handle of a ladle which rests in a honey drink at the foot of the world tree; as the sun wends across the sky, the handle of the ladle turns likewise. The ladle clearly represents the firmament, turning with the sun. No one seems to be responsible for the turning here, a feature shared with the Finnish sampo, but differing from the Norse myths of Mundilfoeri and of Grotti. Comparison Although the Norse seem to have been familiar with the image of the pillar sustaining the world, the world support does not appear as the pivot of the cosmic mill, as it does in Finnish. If the myth of Mundilfoeri is correctly interpreted as the turning of the sky by a handle-like device, then this would represent an adaptation of the cosmic mill, in this case to express a concept of time. The ‘handle’ could be a version of the world support. The turning of the world like a mill is the subject of the (proposed interpretation of) the myth of Mundilfoeri, which is therefore comparable with the turning of the heavens about the sampo. This feature is not apparent in the other Norse myths. Grotti is supernaturally productive, but this productivity is not related by the sources to acts of cosmic creation, as in the Indian myth. Grotti produces both beneficent objects (gold) and maleficent (an army), as does the Indian churning (here may be seen the development of a concept of a ‘wheel of fortune’ out of the basic idea of the fertile mill); the Finnish sampo does not churn out maleficent produce. The myth of Bergelmir seems to involve creative activity (either as a continuation or as an alternative image of primal creation). The myth of Mundilfoeri is not concerned with creation, but with the determining of time, the seasons. The concept of a ‘Golden Age’ is more stressed in the myth of Grotti than in the Finnish and Indian analogues (it does not appear in the other Norse myths). The time of earthly paradise under Fróði also mirrors the early time of the gods recounted in Vsp. 36 Grotti is stolen, like the sampo and the soma; however, in Norse the millstone is not desired—its theft is presented as incidental to a viking attack, whereas in Finnish and Indian the possession of the sampo and soma respectively is the object of the attack. No theft is involved in the other Norse myths. Grotti breaks (but, in SnE, causes the sea’s saltiness); the sampo shatters (but its fragments endow earth and sea with fertility); no breaking of any ‘mill’ is indicated in the other Norse myths. According to SnE Grotti ends up in the sea, like the sampo; however, this is connected with the folk-tale motif of ‘why the sea is salt’ (Thompson A1115), not with fertility as in the Finnish and Indian analogues. By his name and family Bergelmir is closely connected with roaring waters and with fertility. The myth of Mundilfoeri shows no connexion with fertile waters. It is clear that the cosmic mill was not, in extant Norse sources, a widely developed mythologem. Nonetheless, the myth of Mundilfoeri connects the turning of the cosmos via a ‘mill-handle’ with the regulation of seasons, and the myth of Bergelmir suggests the concept of a creative milling of a giant’s body, associated in some way with the sea. Grotti was a legendary mill sunk in the depths, regarded as a one-time producer of a golden age: the myths about it allude to the concept of a milling on a supernatural scale, such as the Bergelmir myth may (in a different context) have exemplified. |

|

IMAGES of OLD NORSE COSMOLOGY The universe imagined as a Lúðr (mill) |

|

|

In 1886, the Swedish poet and scholar, Viktor

Rydberg first made the case for a cosmic mill grinding at the bottom of

the sea in Germanic mythology, based on passages in Eddic and skaldic

poetry. His findings were published in the first volume of his work

Undersökningar i Germanisk Mytologi, subsequently translated into

English in 1889, as Teutonic Mythology, reprinted again as a

three volume edition in 1906. Below is an abridged and edited form of

that argument. Remarkably, it closely mirrors the evidence and argument

in the Tolley article excerpted above. |

||

|

1991 Peter Robinson "Rydberg deserves credit as the first scholar to explain correctly the reference to lúðr in Gróugaldr 11 (p. 509); see pp. 368-9 below." |

||

|

Undersökningar i Germanisk Mythologi, chapters 79-81 by Viktor Rydberg edited and abridged by William P. Reaves

79. THE GREAT WORLD-MILL.

We have yet to mention a place in

the lower world which is of importance to the naive but, at the same

time, perspicuous and imaginative cosmology of Germanic heathendom. The

myth in regard to the place in question is lost, but it has left

scattered traces and marks, with the aid of which it is possible to

restore its chief outlines.

Poems, from the heathen time,

speak of two wonderful mills, a larger and a smaller "Grotti"-mill.

The larger one is simply immense.

The storms and showers which lash the sides of the mountains and cause

their disintegration; the breakers of the sea which attack the rocks on

the strands, make them hollow, and cast the substance thus scooped out

along the coast in the form of sand-banks; the whirlpools and currents

of the ocean, and the still more powerful forces that were fancied by

antiquity, and which smouldered the more brittle layers of the earth's

solid crust, and scattered them as sand and mould over "the stones of

the hall," in order that the ground might "be overgrown with green

herbs" - all this was symbolized by the larger Grotti-mill. And as all

symbols, in the same manner as the lightning which becomes Thor's

hammer, in the mythology become epic-pragmatic realities, so this symbol

becomes to the imagination a real mill, which operates deep down in the

sea and causes the phenomena which it symbolizes.

This greater mill was also called

Græðir, since its grist is the

mould in which vegetation grows. This name was gradually transferred by

the poets of the Christian age from the mill, which was grinding beneath

the sea, to the sea itself.

The lesser Grotti-mill [i.e.

‘Froði’s Mill’, turned by the giantesses Fenja and Menja, as told in the

Grottosöngr] like the greater one, is of heathen origin -- Egil

Skalla-Grímsson mentions it-- but it plays a more accidental part, and

really belongs to the heroic poems connected with the mythology. …After

the introduction of Christianity, the details of the myth concerning the

greater, the cosmological mill, were forgotten, and there remained only

the memory of the existence of such a mill on the bottom of the sea. The

recollection of the lesser Grotti-mill was, on the other hand, at least

in part preserved as to its details in a song which continued to

flourish, and which was recorded in

Skáldskaparmál 43.

…Contrary to the statements of

the Grottosöngr, the tradition narrated there narrates that the mill did

not break into pieces, but stood whole and perfect, when the curse of

the giant-maids on Frodi was fulfilled. The night following the day when

they had begun to grind misfortune on Frodi, there came a sea-king,

Mysing, and slew Frodi, and took, among other booty, also the

Grotti-mill and both the female slaves, and carried them on board his

ship. Mysing commanded them to grind salt, and this they continued to do

until the following midnight. Then they asked if he had not got enough,

but he commanded them to continue grinding, and so they did until the

ship shortly afterwards sank. In this manner the tradition explained how

the mill came to stand on the bottom of the sea, and there the mill that

had belonged to Frodi acquired the qualities which originally had

belonged to the vast Grotti-mill of the mythology.

Skáldskaparmál, which relates

this tradition as well as the song, without taking any notice of the

discrepancies between them, adds that after Frodi's mill had sunk,

"there was produced a whirlpool in the sea, caused by the waters running

through the hole in the mill-stone, and from that time the sea is salt."

80. With distinct consciousness

of its symbolic signification, the greater mill is mentioned in a

strophe by the skald Snæbjörn (Skáldskaparmál

33). The strophe appears to have belonged to a poem describing a voyage.

"It is said," we read in this strophe, "that

Eylúður's nine women violently turn the Grotti of the skerry

dangerous to man out near the edge of the earth, and that these women

long ground Amlodi's lið-grist."

Hvatt kveða hræra Grótta

hergrimmastan skerja

út fyrir jarðar skauti

Eylúður's níu brúðir,

þær er . . . . fyrir löngu

liðmeldr . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . Amlóða mólu.

To the epithet

Eylúður, and to the meaning of

lið- in lið-grist, I shall

return below. The strophe says that the mill is in motion out on the

edge of the earth, that nine giant-maids turn it (for the lesser

Grotti-mill two were more than sufficient), that they had long ground

with it, that it belongs to a skerry very dangerous to seafaring men,

and that it produces a peculiar grist.

The same

mill is suggested by an episode in Saxo, where he relates the saga about

the Danish prince, Amlethus,[1]

who on account of circumstances in his home was compelled to pretend to

be insane. Young courtiers, who accompanied him on a walk along the

sea-strand, showed him a sandbank and said that it was meal. The prince

said he knew this to be true: he said it was "meal from the mill of the

storms" (Hist. Dan., Book 3,

p. 85).

The myth concerning the cosmic

Grotti-mill was intimately connected with the myth concerning the fate

of Ymir and the other primeval giants, and partly with that of

Hvergelmir. Vafþrúðnismál 21 and

Grímnismál 40 tell us that the earth was made out of Ymir's flesh,

the rocks out of his bones, and the sea from his blood. With earth, as

distinguished from rocks, is meant the soil, the sand, which cover the

solid ground. Vafþrúðnismál calls Ymir

Aurgelmir, Mud-gelmir or

Mould-gelmir; and

Fjölsvinnsmál gives him the epithet Leirbrimir, Clay-brimir, which

suggests that his "flesh" was changed into the loose earth, while his

bones became rocks. Ymir's descendants, the primeval giants,

Þrúðgelmir and

Bergelmir perished with him,

and the "flesh" of their bodies cast into the primeval sea also became

mould. Of this we are assured, so far as Bergelmir is concerned, by in

Vafþrúðnismál 35, which also

informs us that Bergelmir was “laid on the mill-box.” The mill which

ground his "flesh" into soil is none other than the one grinding under

the sea, that is, the cosmic Grotti-mill.

When Odin asks the wise giant

Vafþrúðnir how far back he can

remember, and which is the oldest event of which he has any knowledge

from personal experience, the giant answers: "Countless ages before the

earth was created Bergelmir was born. The first thing I remember is when

he var á lúður um lagður."

This expression was misunderstood

by the author of Gylfaginning

himself, and the misunderstanding has continued to develop into the

theory that Bergelmir was changed into a sort of Noah, who with his

household saved himself in an ark when Bur's sons drowned the primeval

giants in the blood of their progenitor. Of such a counterpart to the

Biblical account of Noah and his ark our Germanic mythical fragments

have no knowledge whatever.

The word

lúður (with radical r) has two meanings: (1) a wind-instrument, a

loor, a war-trumpet; (2) the

tier of beams, the underlying timbers of a mill, and, in a wider sense,

the mill itself .

The first meaning, that of

war-trumpet, is not found in the songs of the

Poetic Edda, and upon the

whole does not occur in the Old Norse poetry. Heimdall's war-trumpet is

not called lúður, but

horn or

hljóð. Lúður in this sense

makes its first appearance in the sagas of Christian times, but is never

used by the skalds. In spite of this fact, the signification may date

back to heathen times. But however this may be,

lúður in

Vafþrúðnismál does not mean a

war-trumpet. The poem can never have meant that Bergelmir was laid on a

musical instrument.

The other meaning of Lúðr, partially in its more limited sense of the timbers or beams

under the mill, partially in the sense of the subterranean mill as a

whole, occurs several times in the poems: in the

Grotti-song, in

Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, 2,

and in the above-quoted strophe by Snæbjörn, and also in

Gróugaldur and in

Fjölsvinnsmál. If this signification is applied to the passage in

Vafþrúðnismál: var á lúður um

lagður, we get the meaning that Bergelmir was "laid on a mill," and

in fact no other meaning of the passage is possible, unless an entirely

new signification is to be arbitrarily invented.

But

however conspicuous this signification is, and however clear it is that

it is the only one applicable in this poem, still it has been overlooked

or thrust aside by the mythologists, and for this

Gylfaginning is to blame.[2]

So far as I know, Vigfusson is the only one who (in his

Dictionary, p. 399) makes the passage

á lúður lagður mean what it actually means, and he remarks that the

words must "refer to some ancient lost myth."

The confusion begins, as stated,

in Gylfaginning. Its author

has had no other authority for his statement than the

Vafþrúðnismál strophe in

question. …When Gylfaginning 7

has stated that the frost-giants were drowned in Ymir's blood, then

comes its interpretation of

Vafþrúðnismál 35 as:

"One escaped with his household:

the giants call him Bergelmir. With his wife, he took himself upon his

lúður and remained there, and

from them the races of giants are descended" (nema

einn komst undan með sínu hyski: þann kalla jötnar Bergelmi; hann fór

upp á lúður sinn og kona hans, og hélzt þar, og eru af þeim komnar),

etc.

What

Gylfaginning's author meant by

lúður is difficult to say. In

the meantime, that he did not have a boat in mind is evident from the

expression: hann fór upp á lúður

sinn. From this, it is reasonable to suppose that his idea was, that

Bergelmir himself owned an immense mill, upon whose high timbers he and

his household climbed to save themselves from the flood. That the verse,

which is the source of this information actually says that Bergelmir was

“laid on the lúðr” the author of

Gylfaginning ignores. To go upon something and to be laid on

something are, however, very different notions.

An argument in favor of an

incorrect interpretation was first furnished by the

Resenian edition of the Prose Edda

(

As already pointed out,

Vafþrúðnismál 35 tells us

expressly that Bergelmir, Aurgelmir's grandson, was "laid on a mill-box"

or "on the supporting timbers of a mill." We may be sure that the myth

would not have laid Bergelmir on "a mill" if the intention was not that

he was to be ground. The kind of meal thus produced is the soil and sand

which the sea since time's earliest dawn has cast upon the shores of

Midgard, and with which the bays and beaches have been filled, to sooner

or later become green fields. From Ymir's flesh the gods created the

oldest layer of soil, that which covered the earth the first time the

sun shone thereon, and in which the first herbs grew. Ever since then,

the same activity continues. After the great mill of the gods

transformed the oldest frost-giant into the dust of earth, it continued

to grind the bodies of his descendants between the same stones into the

same kind of meal. This is the meaning of

Vafþrúðnir's words when he

says that his memory reaches back to the time when Bergelmir was ‘laid

on the mill’ to be ground. He does not remember Ymir, nor

Þrúðgelmir, nor the days when these were changed to earth. Of them

he knows only by hearsay. But he remembers when the turn came for

Bergelmir's limbs to be subjected to the same fate.

…When the fields were raised out

of Ymir's blood they were covered with mould, so that, when they got

light and warmth from the sun, then the

grund became

gróin grænum lauki. The very

word mold (mould, earth) comes

from the Germanic word mala,

to grind (cp.

Here, then, we have the

explanation of the lið-meldur

which the great mill grinds, according to Snæbjörn.

Lið-meldur means limb-grist.

It is the limbs and joints of the primeval giants, which are transformed

into meal on Amlodi's mill.

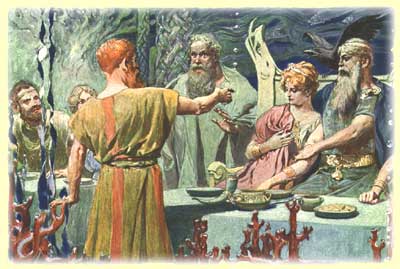

In its character as an

institution for the promotion of fertility, and for rendering the fields

fit for habitation, the mill is under the care and protection of the

Vanir. After Njörd's son, Frey, had been fostered in Asgard and had

acquired the dignity of lord of the harvests, he was the one who became

the master of the great mill. It is attended on his behalf by one of his

servants, who in the mythology is called

Byggvir, a name related both

to byggja, settle, cultivate,

and to bygg, barley, a kind of

grain, and by his kinswoman and helpmate Beyla. So important are the

duties of Byggvir and Beyla that they are permitted to attend the feasts

of the gods with their master (Frey). Consequently they are present at

the banquet to which Ægir, according to

Lokasenna, invited the gods.

When Loki made his appearance there, uninvited, to mix harm in the mead

of the gods, and to embitter their pleasure. When he taunts Frey,

Byggvir becomes angry on his master's behalf and says:

Beyla, too, gets her share of

Loki's abuse. The least disgraceful thing he says of her is that she is

a deigja (a slave, who has to

work at the mill and in the kitchen), and that she is covered with

traces of her occupation, dust and dirt.

As we see, Loki characterizes

Byggvir as a servant taking charge of the mill (kvern) under Frey, and

Byggvir characterizes himself as one who grinds, and is able to crush an

"evil crow" limb by limb with his mill-stones. As the one who makes

vegetation possible with his mill, and so also bread and malt, he boasts

of it as his honor that the gods are able to drink ale at a banquet.

Loki blames him because he is not able to divide food among men. The

reproach implies that the distribution of food is in his hands. The soil

which comes from the great mill gives different degrees of fertility to

different fields, and rewards the toil of the farmer, either abundantly

or niggardly. Loki doubtless alludes to this unequal distribution, else

it would be impossible to find any sense in his words.

In the Poetic Edda we find yet

another reminiscence of the great mill located under the sea, and at the

same time in the lower world (see below), which grinds soil into food.

It is in a poem, whose skald says that he has seen it on his journey in

the lower world. In his description of the "home of torture" in Hel, the

Christian author of Sólarljóð

has taken all his material from the heathen mythological conceptions of

the world of punishment, though the author treats this material in

accordance with the Christian purpose of his song. When the skald dies,

he enters the gates of Hel, crosses bloody streams, sits for nine days

á norna stóli (‘on norns’

seats), is then seated on a horse, and is permitted to make a journey

through Mimir's realm, first to the regions of the happy and then to

those of the damned. In Mimir's realm he sees the "stag of the sun" and

Nidi's (Mimir's) sons, who "drink the pure mead from Baug-regin's well."

As he approaches the borders of the world of the damned, he hears a

terrible din, which silences the winds and stops the flow of the waters.

The mighty din comes from a mill. Its stones are wet with blood, but the

grist produced is mould, which was to be food. Fickle-wise (svipvísar,

heathen) women of dark complexion turn the mill. Their bloody and

tortured hearts hang outside of their breasts. The mould which they

grind is to feed their husbands (Sólarljóð

57-58).

This mill, situated at the

entrance of Hel, is here represented as one of the agents of torture in

the lower world. To a certain extent this is correct even from a heathen

standpoint. It was the lot of slave-women to turn the hand-mill. In the

heroic poem the giant-maids Fenja and Menja, taken prisoners and made

slaves, have to turn Frodi's Grotti. In the mythology "Eyluður's

nine women," thurs-maidens, were compelled to keep this vast mechanism

in motion, and that this was regarded as a heavy and compulsory task may

be assumed without the risk of being mistaken.

According to

Sólarljóð, the mill-stones are stained with blood. In the mythology,

they crush the bodies of the first giants and revolve in Ymir's blood.

It is also in perfect harmony with the mythology that the meal becomes

mould, and that the mould serves as food. But the cosmic signification

is obliterated in Sólarljóð,

and it seems to be the author's idea that men who have died in their

heathen belief are to eat the mould which women who have died in

heathendom industriously grind as food for them.

The myth about the greater

Grotti, has also been connected with the Hvergelmir myth.

Sólarljóð has correctly stated

the location of the mill on the border of the realm of torture. The

mythology has located Hvergelmir's fountain there (cp. Gylfaginning 4);

and as this vast fountain is the source of the ocean and of all waters,

and the ever open connection between the waters of heaven, of the earth,

and of the lower world, then this furnishes the explanation of the

apparently conflicting statements, that the mill is situated both in the

lower world and at the same time on the bottom of the sea. Of the mill

it is said that it is dangerous to men, dangerous to fleets and to

crews, and that it causes the maelstrom (svelgr)

when the water of the ocean rushes down through the eye of the

mill-stone. The same was said of Hvergelmir, that causes ebb and flood

and maelstrom, when the water of the world alternately flows into and

out of this great source. To judge from all this, the mill has been

conceived as so made that its supporting timbers stood on solid ground

in the lower world, and thence rose up into the sea, in which the stones

resting on this substructure were located. The revolving "eye" of the

mill-stone was directly above Hvergelmir, and served as the channel

through which the water flowed to and from the great fountain of the

world's waters.

MUNDILFÆRI.

But the colossal mill in the

ocean has also served another purpose than that of grinding the

nourishing mould from the limbs of the primeval giants.

The Teutons, like all people of

antiquity, regarded the earth as stationary. And so, too, the lower

world (called jörmungrund

in Hrafnagalður

Óðins 25, and in Grímnismál 20) on which the foundations of the earth rested. Stationary

too was that heaven in which the Aesir had their citadels, surrounded

by a common wall, for the Asgard-bridge, Bifröst, had a solid

bridge-head on the southern and another on the northern edge of the

lower world, and could not change position in its relation to them. All

this part of creation was held together by the immovable roots of the

world-tree, or rested on its invisible branches. Sol and Mani had their

fixed paths, the points of departure and arrival of which were the

"horse-doors" (jódyr —Völuspá

5, Hauksbók), which were hung on the eastern and western mountain-walls

of the lower world. The god Mani (moon) and the goddess Sol (sun) were

thought to traverse these paths in shining chariots, and their daily

journeys across the heavens did not imply to our ancestors that any part

of the world-structure itself was in motion. Mani's course lay below

Asgard. When Thor in his thunder-chariot descends to Jötunheim the path

of Mani thunders under him (en

dundi Mána vegur und Meila bróður - "The path of the moon clattered

beneath Meili's brother" (i.e. Thor),

Haustlöng 14). No definite

statement in our mythical records informs us whether the way of the sun

was over or under Asgard.

But high

above Asgard is the starry vault of heaven, and to the Teutons as well

as to other people that sky was not only an optical but a real vault,

which daily revolved around a stationary point. Sol and Mani might be

conceived as traversing their appointed courses independently, and not

as coming in contact with vaults, which by their motions from east to

west produced the progress of sun and moon. The very circumstance that

they continually changed position in their relation to each other and to

the stars seemed to prove that they proceeded independently in their own

courses. With the countless stars the case was different. They always

keep at the same distance and always present the same figures on the

canopy of the nocturnal heavens. They looked like glistening heads of

nails driven into a movable ceiling. Hence the starlit sky was thought

to be in motion. The sailors and shepherds of the Teutons knew very well

that this revolving was round a fixed point, the polar star, and it is

probable that veraldar nagli, the world-nail, the world-spike, an expression

preserved in Eddu-brot II,

designates the northstar.

[3]

Thus the starry sky was the

movable part of the universe. And this motion is not of the same kind as

that of the winds, whose coming and direction no man can predict or

calculate. The motion of the starry firmament is defined, always the

same, always in the same direction, and keeps equal step with the march

of time itself. It does not, therefore, depend on the accidental

pleasure of gods or other powers. On the other hand, it seems to be

caused by a mechanism operating evenly and regularly.

For a long time, the mill was the

only kind of large scale mechanism known to the Teutons. Its motion was

a rotating one. The movable mill-stone was turned by a handle or sweep

which was called möndull. The

mill-stones and the möndull

might be conceived as large as you please. Fancy knew no other limits

than those of the universe.

There was another natural

phenomenon, which was also regular, and which was well known to the

seamen of the North and to those Teutons who lived on the shores of the

The mythology knew a person by

name Mundilfæri (Vafþrúðnismál

23, Gylfaginning 11). The word

mundill is related to möndull,

and is presumably only another form of the same word. The name or

epithet Mundilfæri refers to a being that has had something to do with a

great mythical möndull and

with the movements of the mechanism which this

möndull kept in motion. Now

the word möndull is never used

in the Old Norse literature about any other object than the sweep or

handle with which the movable mill-stone is turned. (In this sense the

word occurs in the Grotti-song

and in Helgakviða Hundingsbana

II, 3, 4). Thus Mundilfæri has had some part to play in regard to the

great giant-mill of the ocean and of the lower world.

Of Mundilfæri we learn, on the

other hand, that he is the father of the personal Sol and the personal

Mani (Vafþrúðnismál 23). This,

again, shows that the mythology conceived him as intimately associated

with the heavens and with the heavenly bodies. Vigfusson (Dict.,

437) has, therefore, with good reason remarked that

mundill in Mundilfæri refers to "the veering round or revolution of

the heavens." As the father of Sol and Mani, Mundilfæri was a being of

divine rank, and as such belonged to the powers of the lower world,

where Sol and Mani have their abodes and resting-places. The latter part

of the name, -færi, refers to

the verb færa, to conduct, to

move. Thus he is that power who has to take charge of the revolutions of

the starry vault of heaven, and these must be produced by the great

möndull, the mill-handle or mill-sweep, since he is called

Mundilfæri.

The

regular motion of the starry firmament and of the sea is, accordingly,

produced by the same vast mechanism, the Grotti-mill, the

meginverk of the heathen fancy

(Grotti-song 11; cp. Egil

Skallagrimson's way of using the word,

Arinbjarnardrápa 25).[4]

The handle extends to the edge of the world, and the nine giantesses,

who are compelled to turn the mill, pushing the sweep before them, march

along the outer edge of the universe. Thus we get an intelligible idea

of what Snæbjörn means when he says that Eyluður's nine women turn the

Grotti "along the edge of the earth" (hræra

Grótta út fyrir jarðar skauti).

Mundilfæri and Byggvir thus each

has his task to perform in connection with the same vast machinery. The

one attends to the regular motion of the

möndull, the other looks after

the mill-stones and the grist.

In the name

Eylúður the first part is ey,

and the second part is lúður.

The name means the "island-mill." Eyludur's nine women are the "nine

women of the island-mill." In the same verse, the mill is called

skerja Grótti, the Grotti of the skerries. These expressions refer

to each other and designate with different words the same idea - the

mill that grinds islands and skerries.

The fate

which, according to the Grotti-song, happened to King Frodi's mill has

its origin in the myth concerning the greater mill. The stooping

position of the starry heavens and the sloping path of the stars in

relation to the horizontal line was a problem which in its way the

mythology wanted to solve. The phenomenon was put in connection with the

mythic traditions in regard to the terrible winter which visited the

earth after the gods and the sons of Ivaldi had become enemies. Fenja

and Menja were kinswomen of Ivaldi's sons. For they were brothers

(half-brothers) of those mountain giants who were Fenja's and Menja's

fathers (Grotti-song 9).

Before the feud broke out between their kin and the gods, both the

giant-maids had worked in the service of the latter and for the good of

the world, grinding the blessings of the golden age on the world-mill.

Their activity in connection with the great mechanism,

möndull, which they pushed,

amid the singing of bliss-bringing songs of sorcery, was a counterpart

of the activity of the sons of Ilvaldi, who made the treasures of

vegetation for the gods. When the conflict broke out, the giant-maids

joined the cause of their kinsmen. They gave the world-mill so rapid a

motion that the foundations of the earth trembled, pieces of the

mill-stones were broken loose and thrown up into space, and the

sub-structure of the mill was damaged. This could not happen without

harm to the starry canopy of heaven which rested thereon. The memory of

this mythic event comes to the surface in

Rímbegla,[5]

which states that toward the close of King Frodi's reign there arose a

terrible disorder in nature -- a storm with mighty thundering passed

over the country, the earth quaked and cast up large stones. In the

Grotti-song the same event is mentioned as a "game" played by Fenja

and Menja, in which they cast up from the deep upon the earth those

stones which afterwards became the mill-stones in the Grotti-mill. After

that "game" the giant-maids proceeded to the earth and took part in the

first world-war on the side hostile to Odin. It is worthy of notice that

the mythology has connected the

fimbul-winter and the great emigrations from the North with an

earthquake and a damage to the world-mill which makes the starry heavens

revolve.[6]

82. THE ORIGIN OF THE SACRED FIRE

THROUGH MUNDILFÆRI. HEIMDALL THE PERSONIFICATION OF THE SACRED FIRE.

Among the tasks to be performed

by the world-mill there is yet another of the greatest importance.

According to a belief which originated in ancient Indo-European times, a

fire is to be judged as to purity and holiness by its origin. There are

different kinds of fire more or less pure and holy, and a fire which is

holy in origin may become corrupted by contact with improper elements.

The purest fire, that which was originally kindled by the gods and was

afterwards given to man as an invaluable blessing, as a bond of union

between the higher world and mankind, was a fire which was produced by

rubbing two objects together (friction). In hundreds of passages this is

corroborated in Rigveda, and

the belief still exists among the common people of various Germanic

peoples. The great mill which revolves the starry heavens was also the

mighty rubbing machine (friction machine) from which the sacred fire

naturally ought to proceed, and really was regarded as having proceeded,

as shall be shown below.

The word

möndull, with which the handle of the mill is designated, is found

among our ancient Indo-European ancestors. It can be traced back to the

ancient Germanic manthula, a

swing-tree (August Fick,

Wörterbuch der

indogermanischen Grundsprache

III,

232), related to Sanskrit Manthati,

to swing, twist, bore,[7]

from the root manth, which

occurs in numerous passages in

Rigveda, and in its direct application always refers to the

production of fire by friction (Bergaigne,

Religion vedique, III. 7).

…Heimdall,

the ‘whitest of the Æsir” was likely born out of this mill. His very

place of nativity indicates this. His mothers have their abodes

við jarðar þröm (Völuspá

in skamma 7) near the edge of the earth, on the outer rim of the

earth, and that is where they gave him life (báru

þann mann). His mothers are giantesses (jötna

meyjar), and nine in number. We find giantesses, nine in number,

mentioned as having their activity on the outer edge of the earth -

namely, those who with the möndull,

the handle, turn the vast friction-mechanism, the world-mill of

Mundilfæri. They are the níu

brúðir of Eylúður, "the Isle-grinder," mentioned by Snæbjörn. These

nine giant-maids, who along the outer zone of the earth (fyrir

jarðar skauti) push the mill's sweep before themselves and grind the

coasts of the islands, are the same nine giant-maids who on the outer

zone of the earth gave birth to Heimdall, the god of the friction-fire.

Hence one of Heimdall's mothers is called

Angeyja, "she who makes the

islands closer,"[8]

and another one is called Eyrgjafa,

"she who gives sandbanks."[9]

Mundilfæri, who is the father of Sol and Mani, and has the care of the

motions of the starry heavens is accordingly also, though in another

sense, the father of Heimdall the pure, holy fire to whom the glittering

objects in the skies must naturally be regarded as akin.[10]

In

Hyndluljóð (Völuspá in skamma 9), Heimdall's nine giant-mothers are named:

Gjálp, Greip, Eistla, Eyrgjafa,

Úlfrún, Angeyja, Imdur, Atla, Járnsaxa. The first two are daughters

of the fire-giant Geirrod (Skáldskaparmál

26). Imdur, from

ím, embers, also refers to fire. Two of the names, Angeyja and

Eyrgjafa, as already shown, indicate the occupation of these giantesses

in connection with the world-mill. This is presumably also the case with

Járnsaxa, "she who crushes the

iron."[11]

The iron which our heathen fathers worked was produced from the sea- and

swamp-iron mixed with sand and clay, and could therefore properly be

regarded as a grist of the world-mill.

Heimdall's

antithesis in all respects, and therefore also his constant opponent in

the mythological epic, is Loki, he too a fire-being, but representing

another side of this element. Natural agents such as fire, water, wind,

cold, heat, and thunder have a double aspect in the Germanic mythology.

When they work in harmony, each within the limits which are fixed by the

welfare of the world and the happiness of man, then they are sacred

forces and are represented by the gods. But when these limits are

transgressed, giants are at work, and the turbulent elements are

represented by beings of giant-race. This is also true of thunder,

although it is the common view among mythologists that it was regarded

exclusively as a product of Thor's activity. The genuine mythical

conception was, however, that the thunder which purifies the atmosphere

and fertilizes the thirsty earth with showers of rain, or strikes down

the foes of Midgard, came from Thor; while that which splinters the

sacred trees, sets fire to the woods and houses, and kills men that have

not offended the gods, came from the foes of the world. The thunderbolt

was not only in the possession of the gods, but also in that of the

giants (Skírnismál), and the

lightning did not proceed alone from Mjöllnir, but was also found in

Hrungnir's hein (hone) and in

Geirrod's glowing missile. The conflicts between Thor and the giants

were not only on solid ground, as when Thor made an expedition on foot

to Jötunheim, but also in the air. There were giant-horses that were

able to wade with force and speed through the atmosphere, as, for

instance, Hrungnir's Gullfaxi (Skáldskaparmál

24), and these giant-horses with their shining manes, doubtless, were

expected to carry their riders to the lightning-conflict in space

against the lightning-hurler, Thor. The thunderstorm was frequently a

víg þrimu,[12]

a conflict between thundering beings, in which the lightning-bolts

hurled by the protector of Midgard, the son of Hlódyn, crossed the

lightning hurled by the foes of Midgard.

Loki and

his brothers Helblindi and Byleistr are

the children of a giant of this kind, of a giant representing the

hurricane and thunder. The rain-torrents and waterspouts of the

hurricane, which directly or indirectly became wedded to the sea through

the swollen streams, gave birth to Helblindi, who, accordingly, received

Rán as his "maid"

(Ynglingasaga 51)*. The whirlwind in the hurricane received as his ward

Byleistr, whose name is composed of

bylr, "whirlwind," and eistr, "the one dwelling in the east" (the north), a paraphrase for

"giant."[13]

A

thunderbolt from the hurricane gave birth to Loki. His father is

called Fárbauti, "the one

inflicting harm,"[14]

and his mother is Laufey, "the leaf-isle," a paraphrase for the

tree-crown (Gylfaginning 33,

Skáldskaparmál 23). Thus Loki

is the son of the burning and destructive lightning, the son of him who

particularly inflicts damaging blows on the sacred oaks (see No. 36) and

sets fire to the groves. But the violence of the father does not appear

externally in the son's character. He long prepares the conflagration of

the world in secret, and not until he is put in chains does he exhibit,

by the earthquakes he produces, the wild passion of his giant nature. As

a fire-being, he was conceived as handsome and youthful. From an ethical

point of view, the impurity of the flame which he represents is

manifested by his unrestrained sensuousness.

83. MUNDILFÆRI'S IDENTITY WITH

LODUR.

The position which we have found

Mundilfæri to occupy indicates that, although not belonging to the

powers dwelling in Asgard, he is one of the chief gods of the Germanic

mythology. All natural phenomena, which appear to depend on a fixed

mechanical law and not on the initiative of any mighty will momentarily

influencing the events of the world, seem to have been referred to his

care. Germanic mythology has gods of both kinds -- gods who particularly

represent that order in the physical and moral world which became fixed

in creation, and which, under normal conditions, remain entirely

uniform, and gods who particularly represent the powerful temporary

interference for the purpose of restoring this order when it has been

disturbed, and for the purpose of giving protection and defense to their

worshippers in times of trouble and danger. The latter are in their very

nature war-gods always ready for battle, such as Odin and Thor; and they

have their proper abode in Asgard, a group of fortified celestial

citadels, whence they have their outlook upon the world they have to

protect -- the atmosphere and Midgard.

The former, on the other hand,

have their natural abode in Jörmungrund's outer zone and in the lower

world, whence the world-tree grew, and where the fountains are found

whose liquids penetrate creation, and where that wisdom had its source

of which Odin only, by self-sacrifice, secured a part. Down there dwell,

accordingly, Urd and Mimir, Night and Day, Mundilfæri with the sun and

the moon, Delling, the genius of the rosy dawn, and Billing, the genius

of the blushing sunset. There dwell the smiths of antiquity who made the

chariots of the sun and moon and smithied the treasures of vegetation.

Mundilfæri is the lord of the regular revolutions of the starry

firmament, and of the regular rising and sinking of the sea in its ebb

and flood. He is the father of the dises of the sun and moon, who make

their celestial journeys according to established laws; and, finally, he

is the origin of the holy fire; he is father of Heimdall, who introduced

among men a systematic life in homes fixed and governed by laws.

Þrymskviða 22 informs us that Heimdall can see the future, like all wise

Vanir can, indicating that Heimdall himself, although the “whitest of

the Æsir, is of the Vanir clan by birth As the father of Heimdall, the

god, Mundilfæri is himself a Vana-god, belonging to the oldest branch of

this race, and in all probability one of those "wise rulers" (vís

regin) who, according to

Vafþrúðnismál 39, "created Njörd in Vanaheim and sent him as a

hostage to the gods (the Aesir)."

From where did the clans of the

Vanir and the Elves come? It should not have escaped the notice of the

mythologists that the Germanic theogony, as far as it is known, mentions

only two progenitors of the mythological races -- Ymir and Buri. From

Ymir develop the two very different races of giants, the offspring of

his arms and that of his feet (see Vafþrúðnismál 33) - in other words,

the noble race to which the norns, Mimir and Bestla belong, and the

ignoble, which begins with Thrudgelmir.

Buri gives birth to Burr (Bor),

and the latter has three sons -

Óðinn, Véi (Vé), and

Vili (Vilir). Unless Buri had more sons, the Vanir and Elf-clans have no

other theogonic source than the same as the Aesir, namely,

Burr. That the hierologists of the Germanic mythology did not leave

the origin of these clans unexplained we are assured by the very

existence of a Germanic theogony, together with the circumstance that

the more thoroughly our mythology is studied the more clearly we see

that this mythology has desired to answer every question which could

reasonably be asked of it, and in the course of ages it developed into a

systematic and epic whole with clear outlines sharply drawn in all

details.

To this must be added the

important observation that Vei and Vili, though brothers of Odin, are

never counted among the Aesir proper, and had no abode in Asgard. It is

manifest that Odin himself with his sons founds the Aesir-race, that, in

other words, he is a clan-founder in which this race has its chieftain,

and that his brothers, for this very reason, could not be included in

his clan. There is every reason to assume that they, like him, were

clan-founders; and as we find besides the Aesir two other races of gods,

this of itself makes it probable that Odin's two brothers were their

progenitors and clan-chieftains.

It can bee demonstrated that the

anthropomorphous Vana-god Heimdall was sent by Vanir as a child to the

primeval Germanic country, to give to the descendants of Ask and Embla

the holy fire, tools, and implements, the runes, the laws of society,

and the rules for religious worship (cp. Rigþula, and the Anglo-Saxon

stories of the boy-king Scef). As an anthropomorphous god and first

patriarch, he is identical with Scef-Rig, the Scyld of the Beowulf poem,

that he becomes the father of the other original patriarch Skjold, and

the grandfather of Kon ungr,the first king.

Above, it

has been demonstrated that Heimdall, the personified sacred fire, is

most likely the son of the fire-producer (by friction) Mundilfari. The

name Lóðurr has no other rational explanation than that which Jakob

Grimm, without knowing his position in the epic of mythology, has given,

comparing the name with the verb

lodern, "to blaze."[15]

Lóðurr is active

in its signification, "he who causes or produces the blaze," and thus

refers to the origin of fire, particularly of the friction-fire and of

the bore-fire. From this it follows that that mythic person who is

Heimdall's father, that is to say, to Mundilfari, the fire-producer is

the one the fire-producer, that is Odin’s brother,

Lóðurr.

[1] This tale in Saxo is the source of William Shakespeare's Hamlet, thus Amlodi is often rendered Hamlet in translation, as in Faulkes' Edda. [2] A survey of the scholarship from the late 1700s to the present demonstrates that lúður is understood as 'ark' in this passage, even to the extent that ON dictionaries now give this as a tenative definition, citing Vafþrúðnismál 35 as its source. For example, see LaFarge/Tucker's Glossary to the Poetic Edda.

[3]

The term veraldar nagli is found on the very last

page of the paper

Edda

mss referred to as AM 748 I 4to, published in vol. II of the

so-called [4] Vigfusson defines ON meginverk as "great works, labour." In Grotti-Song it refers to the labor of the giantesses, and in Arinbjarnardrápa (Egil's Saga ch. 80) to that of the poet and the poem itself. In the latter, Codex Wormianus' megin-verkom appears with the variant morgin-verkom, morning labors (Codex AM, 748), this being the preferred reading. [5] A saga from the 12th century. [6] For a fuller exploration of this theme, see Giorgio de Santilana's Hamlet's Mill (1969) in which he puts forth the idea that various mythologies preserve the memory of an ancient global catastrophe. [7] Ursula Dronke confirms this (PE II, pg. 116): "Völuspá 5/1-4: Möndull (cf. HH, II 3, 4, Grott. 20) is thought to be related to Skr. Manthati, 'to stir, turn round', manthá, --'stirring spoon' (Jan DeVries' Alternordisches etymolisches Wörterbuch, 3rd ed. Leidn, 1977), but there are no related verbs in Gmc, even though variants of möndull (and possibly mundill) are found in all the Scandinavaian languages. If Mundilfæri did mean 'Carrier of the Mill-handle, he would be the upper millstone itself, which 'carries' the möndull/ mundill (fitted into a slot in the stone) and is turned by it. …I would relate the statements in Vsp 5/1-4 and Vafþ 23 to the archiac concept of the cosmic mill, by which the heavens turn on the world pillar, regulating seasons and time, and I would suppose that the lost lines 5/5-8 had made this theme clearer. Since Vigfusson's wise insight, we now have an incisive analysis of comparative mythological material on the themes of the cosmic mill in ON, Finnic, and Indian by C. Tolley. 'The Mill in Norse and Finnish Mythology' SBVS 24 (1994-95) 63-82. [8] Simek's Dictionary of Northern Myth.: "The meaning is uncertain; 'those of the narrow island' (to ey according to deVries, 1977) 'the harasser" (Gering, 1927) or perhaps to geyja 'bark' (Motz, 1981)?" pg. 18 [9] Simek's Dictionary of Northern Myth. "Eyrgjafa (ON 'Sand Donor'?) …As with the other names of these mothers Eyrgafa is probably no older than the lay itself," L. Motz, 1981. [10] Thus the female Sun and the male Moon are children of Odin's brother Lodur, who gave mankind lá and læti and lítur goða. As these are Vanir, they marry among their kin. Based on a comparison of Hyndluljod 11-12 with a passage in Hversu Noregur byggðist which reads "Finnálfur the Old married Svanhildur, known as Gullfjöðr. She was the daughter of Dag, son of Delling and Sól, daughter of Mundilfæri. Their son was Svan the Red, father of Sæfari, who was the father of Úlfr, who was the father of Álfr, who was the father of Ingimundr and Eysteinn," Eysteinn Björnsson suggests the Sun and the Moon produce the beautiful daughters Sunna and Nanna who will survive Ragnarok and drive these cars in their parents stead, and that Heimdall married his sister, the sun, and producing the elf clan. Here Dag is taken for Heimdall, and Delling for Mundilfæri. Rydberg made only the rudest outlines of the geneology of the Vanir and the Elves, and rightly so, as the evidence in this area is scant. [11] Simek's Dictionary of N. Myth: Járnsaxa, ('The one with the iron knife'). [12] víg þrimu presumably 'a tumultuous battle'; used of 'the tumult of battle' in Helgi Hundingsbana I, 7 [13] Simek, DNM pg 51: "The eytmology of Byleistr has not been satisfactorily settled; the second element is probably related to -leiptr lightning and the first perhaps to bylr- wind." [14] Simek, DNM pg. 78: Farbauti "The name means the 'dangerous-hitter' which allows a natural-mythological interpretation in the sense of lightning (Kock, Indogermanische Forsuchgen, 1899) or 'storm' (Bugge, Studien, 1889). [15] The meaning of the name is uncertain. Many etymologies have been offered since. Some identify Lóðurr with Loki. The main evidence used to support this theory is the grouping of Lodur, Hoenir, and Odin for the creation of man in Völuspá; compared to the grouping of Odin, Hoenir, and Loki in Haustlöng and Reginsmál. Since no strong links can convincingly be drawn between Odin's brother Lodur, and Odin's blood-brother Loki, this grouping is likely no more than a poetic analogy. Carla O'Harris suggests that the three sons of Bor were all apprentices of Mimir. Odin, however, is the only successful one. After helping Mimir (Motsognir) create the dwarves, as alluded to in Völuspá 9-10, Lodur (Durin) attempts to sieze Mimir's well for himself, or otherwise steal the precious liquid, and is exiled to the deep south with a band of his followers, where he becomes Surt (Black). As Mundilfæri, he had previously fathered Sol, Mani and Heimdall, as well as become the progenitor of the Alfar, all beings associated with warmth and/or light. In the Eddic poems, Rydberg deduces that Surt's son is known as Suttung and Fjalar, and as Skrymir and Utgard-Loki in Snorri's Edda. Throughout the historical era, this clan remains hostile to the Aesir and Vanir, the clans founded by Odin and Hoenir. |

||||||||||||||

|

1898 J. Rogers Rees "The Norse Element in Celtic Myth"

They remembered the story of the tyrant Frode, who held two captive giant maidens, Fenja and Menja, as mill-maids. The grist they had to grind him out of the quern Grotti was fulfilment of joy and "abundance of riches on the bin of bliss"; meanwhile, however, he allowed them for sleep or rest no longer time than the cessation of the cuckoo's song, or the singing of a single stave. So they grew aweary of the thankless task, and ground for their master fire and death instead. Then came the sea-king Mysing and slew Frode, taking away both mill and maidens to his ship. The new taskmaster commanded that salt should be ground, which was so vigorously done that the ship was sunk ; and as it went down it produced floods and a great whirlpool. But a larger mill had also a place in the mythology of the Norse, one that was simply immense.

"The storms and showers which lash the sides of the mountains and cause their disintegration; the breakers of the sea which attack the rocks on the strands, make them hollow, and cast the substance thus scooped out along the coast in the form of sand-banks"

—all this was symbolised by the larger mill, of which the skald Snaebiorn sang :—

"Men say that Eyludr's nine maidens are working hard turning the Skerry-quern out near the edge of the earth, and that for ages past they have been grinding at Amloði's mealbin (the sea) .... So that the daughters of the Island-grinder spirt the blood of Ymir."

Associated with this mill-myth, but how intimately we cannot tell, for its details no longer exist—probably the pronounced heathenism of it all so clashed with the scriptural account of the Creation that it was purposely permitted to die after the acceptance of Christianity by the Norsemen—associated with this myth was the great flood occasioned by the immense quantity of blood which ran from the wounds of Ymir, the giant, when he was slain by Bor's sons, and which drowned all the giants save one, Bergelmer, who, Noah-like, escaped with his wife upon his lúðr, and ultimately landed on the top of a mountain ; from these two descended the second generation of giants. A considerable difference of opinion exists among Norse scholars as to the meaning of this word lúðr. Frye says that Bergelmer escaped on a "wreck", whilst Dasent calls it, in prose, a "boat", and in poetry a " skiff", and Pigott, a " boat". Thorpe translates the word into "chest" in his prose, and into "ark" in his poetry. Vigfusson gives it as "ark" in one place, and as "box" in another, in his Corpus Poeticum Boreale ; but in translating the "Grotta-Songr" he renders fegins-lúðr as " bin of bliss". In his Dictionary, however, he sets down "bin", more especially a "flourbin", as the equivalent of lúðr; whilst Rydberg, in a learned disquisition on the word, gives his opinion that the object on which Bergelmer found safety in the great flood was in some way intimately connected with the world-mill. Both he and Vigfusson, referring to the phrase vas lúðr um lagidr, agree that it refers to some ancient lost myth. Does it not all simply mean that, in the great flood, Bergelmer possessed himself of the first floating object that would answer his purpose, which chanced to be a bin from the great mill, the property of the gods? In time, the bin, from the use it had been put to, became a boat, then a ship, finally developing into an ark. A touch of poetic justice characterises the incident, permitting, as it does, Bergelmer to escape on a bin of the very mill in which his father's (Ymer's) flesh was ground into earth and his bones into rocks, whilst his blood went to make the mighty waters of the troubling flood. |

Further Reading:

Nordic Salt Legends

The Viking Answer Lady

Hamlet's Mill

Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend

The Fingerprints of the Gods

Graham Hancock

[Introduction][Main Menu][Home]

[Poetic Edda][Snorri's Edda][Scholarly View][World-Mill][Symbolism]

Back to

Germanic Mythology