Somewhere Over the Rainbow......

Images of Old Norse Cosmology

Yggdrasil and the Nine Worlds

[Introduction][Main Menu][Home]

[Poetic Edda][Snorri's Edda][Scholarly View][World-Mill][Symbolism]

III. Inngard and Útgard:

A Modern Scholarly Perspective

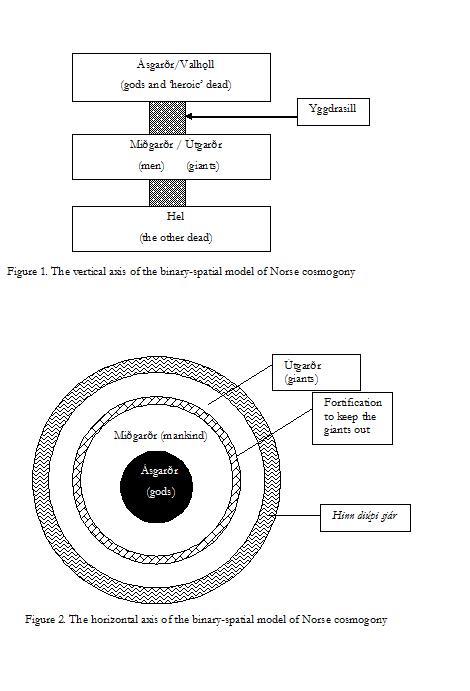

The Binary-Spatial Model

| Since the mid-20th century, a structural interpretation of the Old Norse cosmology has been gaining popularity. Based on Snorri's Edda, this worldview is founded on the concept of an 'inn-gard' where the gods and humans dwell surrounded by an 'ut-gard', home of the giants. |

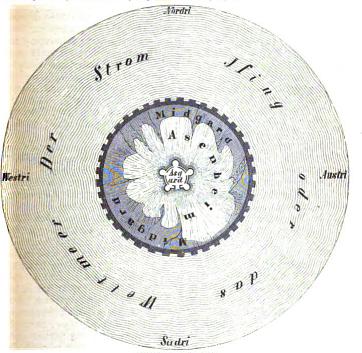

Quite possibly the first illustration of this budding concept occurs in the late 19th century.

1882 Wilhelm Wägner, Jakob Nover

Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden: in Schilderungen für Jugend und Volk

Illustrated by Carl Emil Doepler

"The river Ifing or the World-Sea" surrounds Midgard and Asenheim, 'the home of the Æsir.'

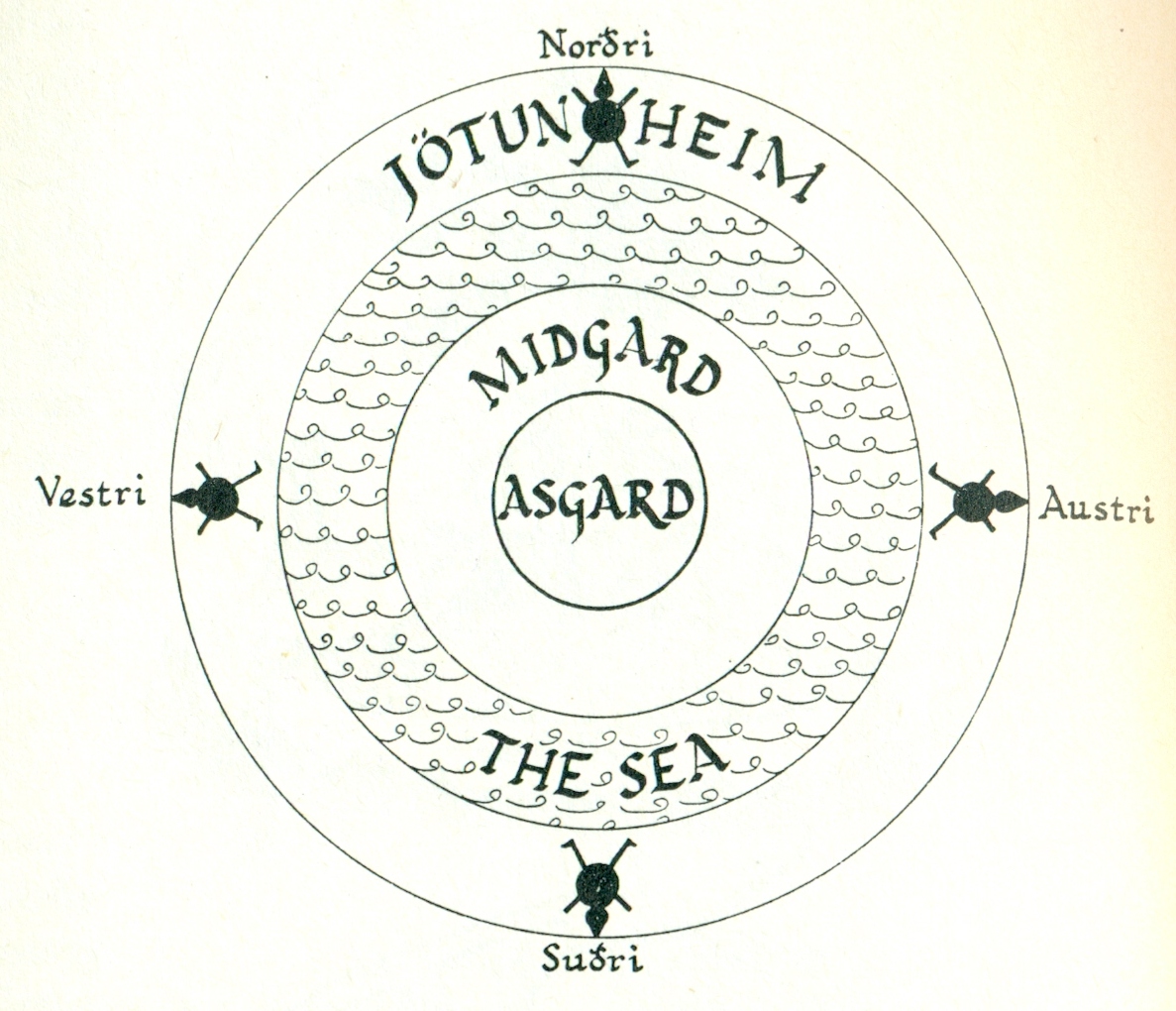

Brian Branstock in Gods of the North, 1955, depicts it this way:

|

|

Now, formally known as the "binary-spatial model", this view developed from a "horizontal model" in which space was defined as moving from a cultured 'inside' (inngard) to a wild 'outside' (útgard). Later a vertical axis was included, represented by Yggdrasil, stretching from Hel to Valhall which mediated between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Within this system, domains at either end of the spectrum are seen as "functional opposites" and said to appear in endless variations. H. A. Molenaar, who refers to this arrangement as "Concentric Dualism", describes it this way: |

|||||

|

|||||

| Christopher Abram (author of Myths of the Pagan North) summarizes the development of the theory in this manner: | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

"The binary-spatial theory was formulated by Meletinskij,

‘Scandinavian Mythology as a System’; significant developments

of the theory were made by Molenaar, ‘Concentric Dualism’, and

Hastrup,

Culture and History,

p. 149. The idea that Yggdrasill mediated structurally between

the living and the dead was offered by Haugen, ‘Mythical

Structure of the Ancient Scandinavians’, p. 182. Strutynski,

‘History and Structure’, criticised Haugen’s methodology as

precluding an empirical approach to the data; more general

doubts as to the validity of the binary-spatial model have been

expressed, particularly by Schjødt, ‘Horizontale und vertikale

Achsen’; see also Clunies Ross,

Prolonged Echoes I, 252-3." |

An excerpt from

1982 H. A. Molenaar

"Concentric Dualism as Transition Between a Lineal and Cyclic

Representation of Life and Death in Scandinavian Mythology"

|

Another

cosmographical arrangement found in the mythical representations is that

formed by the contrast between the land of the giants (Utgarth) on the

one hand and the territory of men and gods (Mithgarth and Asgarth) on

the other. In the prose Edda the earth is said to be round and

surrounded by a deep sea. On the shores of the latter the gods have

given land to the giants to settle. Inland men live in a region called

Mithgarth. Because of the hostility of the giants, Mithgarth is built in

the form of a great round citadel. In the centre of the world the gods

have built a citadel for themselves, called Asgarth. Furthermore, some

poems of the Poetic Edda10

inform us that the border of the land of the giants is a river. In this representation we find the gods

living amidst men. This is not so strange, as gods and men both stand in

a hostile relation to the giants. The giants are represented mostly as

demoniacal beings. They are a constant threat to the order of the world.

The gods, on the other hand, try to maintain this order, and in this way

act as protectors of mankind. We may consider this cosmographical

arrangement as being expressive of an opposition between gods and

giants. This arrangement

calls to mind the distinction between the human territory and

surrounding nature. There are further indications allowing us to compare

giants to forces of nature. They live near the sea, far from the human

territory, or (according to many sources) near mountains and rocks.

Giants are extremely strong and are associated with cold and frost.11

One giant is supposed to bring about the wind (Hræsvelgr), while another

is associated with the sea (Ægir) and yet another with fire (Logi). One

author (Meyer 1903) has even tried to distinguish between several

categories of giants on the basis of the forces of nature they are

associated with (mountain, forest, water, and cloud giants, etc).

Moreover, the giants are descended from the first living being, Ymir,

who displays unmistakable traits of belonging to the vegetable kingdom. However, to speak of an opposition between

culture and nature seems unjustified. The giants have knowledge of magic

and are even Othinn's teachers in this respect (Havamal 140, Voluspa

22). They also have a great store of general wisdom (Vafthruthnismal).

This corresponds with the idea that the giants were the first

inhabitants of the earth and were driven out by the gods, which we come

across in several sources. Further, we read of giants' habitations with

cattle, tilled fields and rich property. The giants are familiar with

the institution of marriage and according to some myths have at their

disposal — although temporarily — cultural goods such mead and Thórr’s

hammer. It seems advisable to consider the giants as

the cosmic opponents of the gods. Even at the creation of the world the

giants and gods were placed in opposition to one another, and this

continues to be so right till the end of the world, when they will fight

one another. We come across giants in this role in many myths. Because

of this many demonic, wild and nature-like traits are attributed to the

giants. However, it is important to realize that the gods and giants can

in principle enter into relation with one another, whether it be a

marriage relation or some other kind of exchange relation, and so do not

belong to orders that are essentially different. This opposition

between gods and giants is expressed on the cosmographical level in the

distinction between Mithgarth (or Asgarth) and Utgarth. In this we

discern a form of concentric dualism that is actualized on the

horizontal plane, whereas the distinction between heaven and underworld

referred to in the previous section was a vertical diametric12

one. We are dealing here with two distinct principles of classification. So on the one hand we

find heaven diametrically opposed to the underworld in a high-low

contrast. On the other hand we see a blending of Utgarth and the

underworld on the horizontal level, on which they are opposed to Asgarth

in a concentric model. Even if we do not consider spatial categories,

this same picture emerges. In the continual conflict between the gods

and the giants, Hel is on the side of the giants. Not only does she

belong to the race of giants, but she will also fight against the gods

together with the other giants during the last struggle, in which the

earth will be destroyed. A third cosmographical arrangement is related

to the conception So we find several spatial arrangements existing side by side in the mythical concepts, in which the same elements recur continually. We have been able to recognize the following forms respectively: diametric dualism, concentric dualism and triadism. We have ascertained that in the concentric arrangement a blending of the underworld and the land of the giants takes place. Consequently we are able to conceive of the concentric model as a transitional form linking up the other two arrangements.13 |

||

Footnotes: 10 Harbarthsljóth, Hymiskvitha 5, Vafthrüthnismal 16. 11 Cf., for example, the name "hrïmthursar" (rime-giants) in Vafthrüthnismal 33 and Grimnismal 31. 12 Diametric in the sense of directly opposed. There is no reference to a representation of the cosmos as a circle divided into two parts. 13 In my opinion the distinction between these three orders corresponds better with the data than the distinction between a horizontal and a vertical world order made by Meletinskij (1973). The opposition between the horizontal and the vertical principle is without any doubt of importance (and plays a part in the discrimination of the diametrical and the concentric model), but is applied too rigorously by Meletinskij. The way the two world orders are related as subsystems that have a subsidiary function with respect to one another is rather problematical. On the other hand, the interrelations of the three orders presented in this essay are placed on a clear structural level. These logical interrelations confirm the value of each individual order. |

|

A

"Snorri

Sturluson

and the Structuralists by Christopher Abram 2003 Representations of the Pagan Afterlife in Medieval Scandinavian Literature [Download Complete Text]

In Gylfaginning, Snorri Sturluson is perfectly clear about who goes to Hel: ‘hon skipti öllum vistum með þeim er til hennar váru sendir, en þat eru sóttdauðir menn ok ellidauðir’ (SnE I, 27: ‘she has to administer board and lodging to those sent to her, and that is those who die of sickness or old age’). He is equally specific about who is received by Óðinn in Valhöll:

Óðinn heitir Alföðr,

þvíat hann er faðir allra goða. Hann heitir ok Valföðr,

þvíat hans óskasynir eru allir þeir er í val falla. Þeim skipar hann

Valhöll

ok Vingólf, ok heita þeir þá einherjar.[1]

For critics influenced by structuralism, this bipartite division between the dead who go to Óðinn and the dead who sink down to Hel is a crucial one. One of the chief products of structurally-informed theories of Old Norse myth is the ‘binary-spatial’ model of pre-Christian cosmogony. This model works around two axes – the vertical and horizontal – that are mediated in the world tree Yggdrasill. Hel, unambiguously placed under the earth through its etymological links with the grave, is an integral part of the tripartite vertical axis that has the realm of the gods at the top, human beings occupying the middle earth, and Hel, the realm of the dead, at the bottom (see fig. 1).[2] Valhöll is usually placed in the same sphere as the world of the gods. Grímnismál 8, lines 1-2, states that ‘Glaðsheimr heitir inn fimti, þars en gullbiarta / Valhöll víð of þrumir’ (‘The fifth is called Glaðsheimr, where gold-bright Valhöll spreads broad’). Snorri identifies Glaðsheimr as the site of the Æsir’s thrones (SnE I, 15). Óðinn is closely connected with both realms, being both chief of the gods and lord of the dead. The horizontal axis of the binary-spatial model, as illustrated by Klaus von See, is a series of concentric circles, each occupied by one category of beings, starting with the gods at the centre in Ásgarðr, with men living ‘underneath’ Miðgarðr, and the giants living outside the heimr, what von See calls the ‘bewohnte Welt’ (see fig. 2).[3] The evidence for this schema of the horizontal spatial dimension is taken mainly from Snorri’s description of the creation of the world:

Hét karlmaðrinn Askr, en konan Embla, ok ólusk

þaðan af mannkindin þeim er bygðin var gefin undir Miðgarði. Þar næst

gerðu þeir sér borg í miðjum heimi er kallaðr er Ásgarðr. Þat köllum

vér Trója. Þar bygðu guðin ok ættir þeira.[4]

The worlds of men and gods are separated from that of the giants by a fortification, and the sea circumscribes the whole:

Hon er kringlótt útan, ok

þar útan um liggr hinn djúpi sjár, ok með þeiri sjávar ströndu

gáfu þeir lönd

til bygðar jötna ættum. En fyrir

innan á jörðunni gerðu þeir borg

umhverfis heim fyrir ófriði jötna.[5]

According to the account of the creation given in chapter 8 of Gylfaginning, Hel does not have a spatial position in the horizontal dimension, yet it has also been argued that Hel has a place on the horizontal axis, as a facet of Útgarðr, the hostile ‘outside’ which is opposed by Miðgarðr, the inner world of men.[6] This theory might be supported by one reference in Gylfaginning, which places the road to Hel in both a downward and a northerly direction:

‘Hann svarar at “ek skal ríða til Heljar at leita Baldrs. Eða hvárt hefir þú nakkvat sét Baldr á Helvegi?

‘En hon sagði at Baldr hafði þar riðit um

Gjallar brú, “en niðr ok norðr liggr Helvegr.”[7]

The neat equivalence between horizontal and vertical dimensions within the cosmogony may appeal to the structuralist’s desire for ‘general patterns and structural recurrences’,[8] but there are considerable problems with such an approach. Any attempt to fit Hel into the horizontal axis founders due to lack of evidence: as Schjødt points out, the giants that are the conventional inhabitants of Útgarðr do not dwell in Hel, but are subject to death like mortal men, as can be seen when Þórr strikes the giant-builder so hard that he sends him down beneath Niflhel (SnE I, 35: ‘ok sendi hann niðr undir Niflhel’). So, even for the giants, who are located on the ‘outside’ in the horizontal axis, death brings about a shift to the vertical, made explicit in the giant-builder’s exit downwards. Schjødt’s conjecture about the reasoning behind Snorri’s placing Hel in the North – the direction of the coldest weather, differentiating it from the traditionally hot Christian inferno – is dubious,[9] but his insistence that Hel was first and foremost ‘below’, and that it did not perform a function analogous to Útgarðr, seems a necessary one.[10] Hel may have no place on the horizontal axis of the binary-spatial schema, but it does seem to fulfil an important requirement in the vertical dimension. There is, on the other hand, very little evidence to suggest that Valhöll (or Ásgarðr) merits its position on top of the worlds. There is a single eddic reference to a figure ascending into the sky on her journey into the otherworld in Helgakviða hundingsbana II 49, although the realm is not specifically named as Valhöll:

Mál er mér at ríða roðnar brautir, láta fölvan ió flugstíg troða; scal ec fyr vestan vindhiálms brúar, áðr Salgofnir sigrþióð veki.[11]

This stanza does appear to refer to Valhöll in its last line, with sigrþioð ‘victory-people’ referring to the einherjar, and Salgofnir ‘hall-cock’ presumably identifiable with the cockerel Gullinkambi who is said to crow at Heriaföðrs (‘at Óðinn’s place’) in Völuspá 43, line 2. Helgi, who speaks this verse, is a fallen warrior and a member of the einherjar, which explains why he must hurry back to Valhöll before the sigrþióð wakes. The strong implication here is that his route back to Valhöll will take him through the sky, but nowhere else in the Poetic Edda is this idea mentioned. Skaldic poets hardly ever refer to Valhöll, but in stanza 21 of Egill Skallagrímsson’s Sonatorrek, the poet’s son is said to have gone upp í Goðheim (‘up into the world of the gods’).[12] If Goðheimr was equivalent to Valhöll in Egill’s mind, then his verse would seem to support the view that the twin realms of the gods and the dead were believed to lie ‘above’. The paucity of references to this idea in the poetry, however, leads me to think that the case for this facet of the vertical axis has been overstated, although perhaps Gurevich went too far in writing that ‘there is no reason to suppose that the Scandinavians imagined their gods to be inhabitants of some heavenly spheres’.[13] The single phrase upp í Goðheim in Egill’s Sonatorrek suggests otherwise, and gives room for doubt. Gylfaginning, too, places the gods in the heavens, although the description Snorri gives of the place he calls Himinbjörg is strongly suggestive of Christian influence:

Þar er enn sá staðr er Himinbjörg heita. Sá stendr á himins enda við brúar sporð, þar er Bifröst kemr til himins. Þar er enn mikill staðr er Valaskjálf heitir. Þann stað á Óðinn. Þann gerðu guðin ok þökðu skíru silfri, ok þar er Hliðskjálfin í þessum sal, þat hásæti er svá heitir. Ok þá er Alföðr sitr í því sæti þá sér hann of allan heim. Á sunnanverðum himins enda er sá salr er allra er fegrstr ok bjartari en sólin, er Gimlé heitir. Hann skal standa þá er bæði himinn ok jörð hefir farizk, ok byggja þann stað góðir menn ok réttlátir of allar aldir.[14]

The correspondences found in this passage with the Christian heaven, particularly in the description of the shining, eternal hall Gimlé, populated by the good and righteous of allar aldir, are obvious. The names of the gods’ dwellings derive from poetic sources (including Himinbjörg, which is the name of Heimdallr’s home according to Grímnismál 13), but they are placed within a schema, unique to Snorri, which implicitly equates them with features derived from Christian lore.[15] The vertical axis of the structuralists’ binary-spatial model is altogether more appropriate to a Christian worldview, in which heaven was always thought to be celestial. It is safe to say that Hel’s place on a vertical axis of the Norse mythological cosmos is secure, but that only in Snorra Edda is the conception of a connected realm of the gods and the dead located in the sky fully developed. Whether the binary-spatial model as a whole really does reflect the ‘reality’ of Old Norse mythology is therefore extremely doubtful, because of its absolute reliance on the evidence of Snorra Edda. Even the proponents of structural analysis admit the limitations of Snorri as a source for pre-Christian belief:

Our knowledge of pre-Christian Scandinavian mythology stems from the writings of a Christian scholar, living in Iceland two centuries after Christianity had been accepted as the national faith … obviously this makes it very doubtful whether what Snorri depicts as the heathen worldview was actually ‘heathen’ at all.[16]

It seems unquestionable that the substance of Snorri’s description of Norse cosmogony owes something to his Christian background and upbringing as well as to his knowledge of mythological poetry, and that the form of his description is determined by his desire to reconcile the two worlds in a literary form.[17] Gylfaginning, and to an extent Grímnismál, are the only texts that offer anything like a comprehensive description of pagan Norse cosmogony. As the binary-spatial model rests primarily on Gylfaginning, its validity as the structural underpinning of Norse myth depends on an acceptance of Gylfaginning as a reliable source. It will be seen that the neat equivalences and oppositions established by proponents of the binary-spatial model are not validated by sources outside of Snorra Edda, and that accordingly the whole theory can only safely be applied to Gylfaginning. Structuralism has provided a further meta-myth of a pagan Norse belief system; unlike Snorri, modern structuralists have failed to consult sufficiently widely in the source texts, and their meta-myth is implausible as a result.

Hel looms large in the binary-spatial conception

of Norse myth: larger, perhaps, than it does in the texts. As well as

its function in the spatial schematisation, Hel is a crucial part of the

hypothesised bi-polar structure of pre-Christian beliefs about the

afterlife, because it stands in clear and direct opposition to Valhöll,

the heroic warrior-paradise ruled by Óðinn. For the structuralists, the

separating out of the dead who go to Óðinn from the dead who sink down

to Hel is vital. It enables more opposing pairs to be added to the

structural framework relating to death in Scandinavian myth. In

particular, Hastrup establishes a suggestive set of oppositions that

characterises, for her, the structure of Snorra Edda’s

description of the afterlife (see table 1).[18]

Table 1: Oppositions between the two rival

conceptions of the afterlife in Scandinavian mythology.

As table 1 shows, the categories correspond

exactly. Each conception of the afterlife has a mythical figure to

represent it, a place in the spatial system, a gender signification and

a socio-economic resonance.[19]

Entry to Valhöll

is exclusive: the very name, with the ambivalence of its first element –

does it derive from valr, ‘the

slain’, or val,

‘choice/selection’? – indicates as much.[20]

The word valkyrie means

‘chooser of the slain’, and Snorri emphasises the choosiness of Óðinn’s

handmaidens: ‘Þessar heita valkyrjur. Þær sendir Óðinn til hverrar

orrustu. Þær kjósa feigð á menn ok ráða sigri. Guðr ok

We might propose a further paired opposition,

were we concerned with promulgating the binary-spatial model: Valhöll

was valorised, and even glamorised, and as such we would logically

expect Hel to be stigmatised. This opposition might well be supported by

the description of the realm in Gylfaginning.

Snorri’s description of the hall is truly that of a pagan paradise, and

it is his account which forms the basis of the popular modern conception

of ‘

Valhall or Valhalla (ON Valhöll, ‘hall of the slain’) is the name of Odin’s home in Asgard where he gathers the warriors slain in battle around him … Valhall is situated in the part of Asgard called Glaðsheimr; the hall is thatched with spears and shields, and armour lies on the benches. The valkyries lead the slain heroes (the einherjar) to this hall, to Odin, and they serve them with meat from the boar Sæhrímnir (which the cook Audhrímnir prepares in the cauldron Eldhrímnir).

Simek goes on to describe the endless drink which accompanies the everlasting pork supper, the mead which flows from the udders of the goat Heiðrun. The einherjar fight all day, but are resurrected each evening to return to the feast. ‘This’, writes Simek, ‘seems to give an impression of how Viking Age warriors imagined paradise’. The word ‘paradise’ is loaded with meaning by dint of its primary association with the Christian heaven. It connotes a perfect, blissful state of existence, beyond that which is attainable by men while they are on earth, and reserved for the select bands of the blessed. Simek’s description of Valhöll therefore implicitly equates the Norse realm of the dead with the Christian heaven. By logical extension, Hel would exist in the same relation to Valhöll, as does the Christian inferno to heaven. But while the meta-myth insists that Valhöll was conceived as a paradisiacal state of existence for the soul of the elect, the literary evidence, once again, presents a less coherent picture. [1] SnE I, 21: ‘Óðinn is called All-father, for he is father of all the gods. He is also called Father of the slain, since all those who fall in battle are his adopted sons. He assigns them places in Valhöll and Vingolf, and they are then known as the einherjar [the ‘lone warriors’].’ [2] The binary-spatial theory was formulated by Meletinskij, ‘Scandinavian Mythology as a System’; significant developments of the theory were made by Molenaar, ‘Concentric Dualism’, and Hastrup, Culture and History, p. 149. The idea that Yggdrasill mediated structurally between the living and the dead was offered by Haugen, ‘Mythical Structure of the Ancient Scandinavians’, p. 182. Strutynski, ‘History and Structure’, criticised Haugen’s methodology as precluding an empirical approach to the data; more general doubts as to the validity of the binary-spatial model have been expressed, particularly by Schjødt, ‘Horizontale und vertikale Achsen’; see also Clunies Ross, Prolonged Echoes I, 252-3.

[3]

Von See, Mythos und Theologie,

p. 42.

[4]

SnE I, 13: ‘The man was called

Askr, the woman Embla, and from them was produced the mankind to

whom the dwelling-place under Miðgarðr was given. After that

they made themselves a city in the middle of the world which is

known as Ásgarðr. We call it [5] SnE I, 12: ‘It is circular around the edge, and around it lies the deep sea, and along the shore of this sea they gave lands to live in to the races of giants. But on the earth on the inner side they made a fortification round the world against the hostility of giants.’ [6] See Meletinskij, ‘Scandinavian Mythology as a System of Oppositions’, pp. 251-2. [7] SnE I, 47: ‘He replied: “I am to ride to Hel to seek Baldr. But have you seen anything of Baldr on the road to Hel?” And she said that Baldr had ridden there over Gjöll bridge, “but downwards and northwards lies the road to Hel”.’ On this passage see below, pp. 178-86. [8] Hastrup, Culture and History, p. 147. [9] See below, pp. 179-80. [10] Schjødt, ‘Horizontale und vertikale Achsen’, pp. 47-9. [11] ‘It is time for me to ride the reddened paths, to have the pale horse tread the flight-path; I must go west of windhelm’s bridge, before Salgofnir wakes the victory-people.’ [12] This verse is discussed in detail in the next chapter: see below, pp. 113-14. [13] Gurevich, ‘Space and Time’, p. 46. See also Grundy, ‘Cult of Óðinn’, pp. 110-13; Neckel, Walhall, p. 25. [14] SnE I, 20: ‘There is also a place called Himinbjörg. It stands at the edge of heaven at the bridge’s end where Bifröst reaches heaven. There is also a great palace called Valaskjálf. This place is Óðinn’s. The gods built it and roofed it with pure silver, and it is there in this hall that Hliðskjálf is, the throne of that name. And when All-father sits on that throne he can see over all the world. At the southernmost end of heaven is the hall which is fairest of all and brighter than the sun, called Gimlé. It shall stand when both heaven and earth have passed away, and in that place shall live good and righteous people for ever and ever.’ [15] See Holtsmark, Studier i Snorres Mytologi, pp. 35-8. [16] Hastrup, Culture and History, p. 146. Her anthropological methodology, however, allows her to effectively overlook the weaknesses in her source material: ‘Once we allow ourselves to read his work anthropologically … its validity ‘stretches out’ and comes to encompass the entire generalized world-view of the Icelanders, whether heathen or Christian. Structural recurrences point to a conceptual continuity which exists before and outside particular literary products. These in their turn, may influence popular representations of the structural patterns, which may in consequence become gradually ‘twisted’ or changed … [these structures are not unchangeable, but] they seem to outlive the events through which the analyst gets access to them’ (p. 147). Hastrup’s attitude is unsurprisingly influenced by the father of structural anthropology, Claude Lévi-Strauss, who wrote that structuralism ‘eliminates a problem which has been so far one of the main obstacles to the progress of mythological studies, namely, the quest for the true version, or the earlier one. On the contrary, we define the myth as consisting of all its versions; to put it otherwise: a myth remains the same as long as it is felt as such’. (‘Structural Study of Myth’, p. 435.) [17] Holtsmark, Norrøn mytologi, p. 14. [18] Hastrup, Culture and History, p. 149. [19] Molenaar adds a further opposition to the system: he contrasts the abundance of food and drink in Valhöll with the hunger and thirst associated with Hel in Gylfaginning (‘Concentric Dualism’, p. 32). [20] In stanzas 2 and 14 of Atlakviða, Valhöll is the name given to a human dwelling, which would perhaps be inappropriate to gloss as ‘hall of the slain’: scholars have generally interpreted the name in this instance as ‘foreign hall’, with the val- element here meaning ‘Welsh’, and thus ‘foreign’ by extension. On the possible range of interpretations of Valhöll’s occurrence in Atlakviða, see Dronke, ed., Poetic Edda I, 47.

[21]

SnE I, 30: ‘These are called

valkyries. Óðinn sends them to every battle. They allot death to

men and govern victory. Guðr and

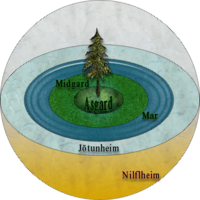

An excerpt from Contradictory cosmology in Old Norse myth and religion – but still a system? by Eldar Heide Maal og Minne 1 (2014): 102–143 The conception of cosmology in Nordic pre-Christian religion and myth has been the subject of much discussion. The sources present a vague, somewhat contradictory picture, which has given rise to a number of different interpretations. Snorri claims that the earth was imagined to be disc-shaped, surrounded by ocean, with Jǫtunn settlements along the coasts, inside of which the region of men, Miðgarðr, was supposed to lie, fenced in with bastions against the Jǫtnar. In the centre of this theregion of gods, Ásgarðr, was finally situated (Gylfaginning 8–9 = Edda Snorra Sturlusonar 1931: 22 ff. 2). Snorri locates the living quarters of the gods in the heavens, and Hel, the land of the dead, below the earth. At the centre of the earth stands Yggdrasill, the World tree. Scholarship on Nordic cosmology has by and large accepted this model. Handbooks and other scholarly literature (overview in Løkka 2010: 18 ff.) often use a horizontal model consisting of three concentric circles to describe Old Norse cosmology: in the middle, the World tree stands, surrounded by Ásgarðr, outside of which is the Miðgarðr of men, outside of that is Útgarðr, home of the Jǫtnar. Steinsland (2005: 98 ff.), for instance, says: “Outside and around Ásgarðr the world of humans unfolds; this place iscalled Miðgarðr. As the name implies, the humans live ‘in the middle’; they are located between the gods and the Jǫtnar. This position tells ussomething about Nordic man’s experience of life: the humans are creatures living in constant tension between different forces” (my translation). Many scholars supplement this horizontal ring model with a vertical axis stretching along the roots, stem and crown of Yggdrasill: the tree reaches from the underworld, up and through this world, and into the heavens. Various mythological creatures inhabit this ‘tree axis’. Some interpreters (e.g., Meletinskij 1973a, 1973b; Hastrup 1981, 1990) agree with Snorri that the gods have their place in the heavens, but this is rejected by Schjødt (1990: 40 ff.): he believes that this owes to Christian influence, stating that only Snorri arranges things in this way, not the poetic Edda and Skaldic poetry. Schjødt says that the older sources portray the heavens only as a path in which the gods travel, and not as a dwelling place. He therefore imagines that the vertical axis consists of the underworld and the earth’s surface only. Another controversial aspect of the cosmological standard model is the number of worlds. Most scholars follow the threefold partition, but structuralists (such as Meletinskij & Hastrup) consider Miðgarðr and Ásgarðr together as one region, so that the sum total amounts to two: Miðgarðr and Útgarðr. This world view will then fit the structuralist notion of human mentality organising the world in opposite pairs. The structuralists (foremostly Gurevich 1969, Meletinskij 1973a, 1973b; Hastrup 1981, 1990) also connect the opposition between Miðgarðr and Útgarðr with the ‘inland’ and ‘outland’ on a farm, and with further general opposite pairs such as in:out; known:unknown; centre: periphery; etc. They accordingly link the mythological macrocosm to the microcosm of everyman.

This model has gained wide impact, especially in the field of archaeology, but has faced some opposition in recent years. Clunies Ross (1994:51) believes that the notion of only one region outside of Miðgarðr does not agree with the source texts, which speak of several regions, oftennine. She suggests that the evidence favours rather “a spatial conceptualism of a series of territories belonging to different classes of beings arranged like a series of concentric half-circles, the perimeter of each cir-cle being imagined as a kind of protective rampart, a garðr.” Moreover, Clunies Ross observes that the term Útgarðr is hardly documented at all– it does not appear in poetry and only once in Snorra Edda, pertaining to the abode of the enigmatic, untypical Jǫtunn Útgarða-Loki. Jǫtunheimar is the name for the region of the Jǫtnar in the older sources. Brink (2004) goes further in this direction and rejects the structuralist, binary model altogether, finding reason to believe the cosmology to “have been more complex, with a larger number of spheres and poles than two” (Brink 2004: 297), and enumerating Mannheimar ‘abode of men’, Þrúðheimr ‘abode of powers(?)’, Jǫtunheimar ‘abode of giants’, Muspellsheimr ‘world of fire (farthest to the south)’; and so on (ibid.: 294).

Brink (2004) concludes: Really it is impossible to try to create a spatial logic out of the mythical rooms and places appearing in Snorri’s narrative. [...] It is not an improvement, though, to try to structuralise the bits and pieces found in the Poetic Edda into a world system. [...] The ancient Scandinavian world model was not a logically structured system, but – as so typical of oral culture – an unstructured, mutable number of rooms and abodes [...]. Innumerable illogicalities and apparently impossible repetitions appear. (Brink 2004: 296–97; my translation). Wellendorf independently arrives at the same conclusion (Wellendorf 2006: 52, based on a lecture in 2004). Schjødt also says that “there were not any consistent ideas about the mythic geography”, although in a foot-note, without expanding further upon the idea (1995: 23). On the other hand, the recent dissertation of Løkka on ancient Nordic cosmology defends the bipartition. After a close reading of the most reliable corpus, the mythological Eddic poems, she concludes that they “spring from a cosmology characterized by a basic opposition between the world of gods and the world surrounding it, an opposition which primarily seems to concretize the categories of in- and outside ” (regardless of whether the outside is explicitly called Útgarðr or not; Løkka2010: 115; my translation). Løkka accordingly supports a “cosmological base model consisting of two primary components, Ásgarðr and its surroundings”, even if “it is obvious that the region outside of Ásgarðr […]consists of a number of lesser regions”

...I believe that to a great degree there is a basis for a model in which the realms of gods, men and Jǫtnar circularly surround each other with the World tree in the middle, corresponding on a cosmological level to the tuntre (‘courtyard tree’), gardstun (‘courtyard’), innmarka (‘inland’) and ut-marka (‘outland’) on a farm (Modern Norwegian forms). To be sure, the placement of men as a belt in-between the gods and the Jǫtnar ought to be rejected as a construction of Snorri, but the rest seems to be correct. In Iron Age agricultural society, most people inhabited a personal environment that often had a farmyard tree in the middle, surrounded by houses and the cultivated land, outside of which lay the areas that were uncultivated but still resourceful, housing powers over which one did not exercise control. This is in accordance with the world of gods, having the World tree in the middle, surrounded by the homesteads of the gods, outside of which are all ‘the others’, whom the gods do not fully control, but which represent important resources and potential. This is the model at which Løkka 2010 arrives, entirely correctly in my opinion – except that I believe that it stands in need of revision in one important aspect: The other realms do not keep a (mytho-)geographical location in relation to the realm of gods, nor in relation to each other. Each realm – for instance Hel and the individual Jǫtunn homesteads – is instead closed within itself, like a ‘bubble’ (of the flat type I have described above). The different realms are not situated in one or another direction from other ‘bubbles’, nor inside others, but they have interfaces with, and passage- ways to, other ‘bubbles’. They are not located in any geographical coordinates, but simply ‘beyond the passageways’. It may seem strange that such a system could work without the realms having a geographical location in relation to each other, but we must remember that mythological geography is always tied to myths, and subordinate to narratives. Then it works, since in the myths, only two realms are in focus at the time, or to be more precise: the realm which one occupies and another one, which is accordingly ‘the other’ seen from the point of view of the first one. |

1974 Eleazar Meletinskij

Scandinavian Mythology as a System of Oppositions

1994 Margaret Clunies Ross

"A Temporal View of Major Mythic Events"

an excerpt from Prolonged Echoes: Vol. I, 1994

2001 John Lindow

The Nature of Mythic Time

an excerpt from Handbook of Norse Mythology

2002 Paul Acker & Carolyne Larrington, ed.

The Poetic Edda: A Collection of Essays

[Poetic Edda][Snorri's Edda][Scholarly View][World-Mill][Symbolism]

Back to

Germanic Mythology