All of the names of the gods and godddesses mentioned

here have counterparts in the Eddas except Phol and

Sinthgunt.

"A number of questions arise in connection with this

interesting relic of German antiquity. Is the Phol of

the first line identical with the Balder of the second

line? Is the Balder here mentioned identical with the

beautiful, luminous god Balder of Norse mythology? Is

Sinthgunt the Moon? And what significance

attaches to the personification of the Sun? " —Frederick

H. Wilkens (1905)

"The contents of this charm are thus: two gods Wodan (=

Odin) and Pol or Phol ride together to the woods, where

one's horse sprains his foot. It is charmed first by

four goddesses and then by Odin, who heals the injury.

By all appearances, Phol must be the injured horse's

master, since he alone is regarded as a kind of patient,

who consequently does not participate in the healing.

However, this is comparatively immaterial, and one can

very well allow that Odin is designated by the word

"balderes." That it alludes to a third person named

Balder however

is hardly conceivable, since this is forbidden by the

context: it is the only Phol and Wodan who ride into the

forest. In Anglo-Saxon, the word means "Lord," and we

must suppose that Balder was an epithet for Odin or

Phol. But who is this Phol?

"It is scarcely possible that a god, who was so genteel

he rode in company with Odin, was able to so completely

disappear that he has left behind no mark in the

mythological sources we have, and yet it seems that way,

because no one has been able to find a Germanic

god, who is thought to hide behind a Pol or Phol,

with any degree of plausibility. And to this

peculiarity joins another. The name has been written

Pol, but then over the line the scribe has added a small

h, so that the name becomes Phol. One suspects then feel

that this has been done for alliteration (because the

words then read: Pfol ende Wodan fuorun zi holza).

The result is still rather meager, because ph (= pf) is

in every instance a weak alliteration for v (=f) in

vuornn. And besides, one would expect the god-pair

Phol ende Wodan to have allitterated like

Sinhtgunt and Sunna and Friia and Volla. " —Henrik

Schück (1904)

"Grimm seems to refer [bonfires lit at Beltane] to the cult of Baldr or

Baeldseg, with which he connects the name Beltane; but

taking all the circumstances into consideration, I am

inclined to attribute it rather to Frea [Freyr], if not

even to a female form of the same godhead, Fricge, the

Aphrodite of the North. Frea [Freyr] seems to have been

a god of boundaries; probably as the giver of fertility

and increase, he gradually became looked upon as a

patron of the fields. On two occasions his name occurs

in such boundaries, and once in a manner which proves

some tree to have been dedicated to him. In a charter of

the year 959 we find these words: "'ðonne andlang

herðaftes on Frigedaeges treów,"—thence along the road

to Friday's (that is Frea's) tree

[Cod. Dipl. No. 1221]; and in a similar document

of the same century we have a boundary running "oð ðone

Frigedaeg." There is a place yet called Fridaythorpe, in

Yorkshire. Here Frigedaeg appears to be a formation

precisely similar to Baeldaeg, Swaefdaeg, and Waegdaeg,

and to mean only Frea himself.

"Baldaeg, in Old Norse BALDR, in Old-German PALTAC.—The

appearance of Baeldaeg among Woden's sons in the

Anglo-Saxon genealogies, would naturally lead us to the

belief that our forefathers worshiped that god whom the

Edda and other legends of the North term Baldr, the

father of Brand, and the Phoebus Apollo of Scandinavia.

Yet beyond these genealogies we have very little

evidence of his existence. It is true that the word

bealdor very frequently occurs in Anglo-Saxon

poetry as a peculiar appellative of kings,—nay even as a

name of God himself,—and that it is, as far as we know,

indeclinable, a sign of its high antiquity. This word

may then probably have obtained a general signification

which at first did not belong to it, and been retained

to represent a king, when it had ceased to represent a

god. There are a few places in which the name of Balder

can yet be traced: thus Baldersby in Yorkshire,

Balderston in Lancashire, Bealderesleah and

Baldheresbeorh in Wiltshire: of these the two first may

very likely have arisen from Danish or Norwegian

influence, while the last is altogether uncertain. Save

in the genealogies the name Baeldaeg does not occur at

all.

"But there is another name under

which the Anglo-Saxons may possibly have known this god,

and that is Pol or Pal.

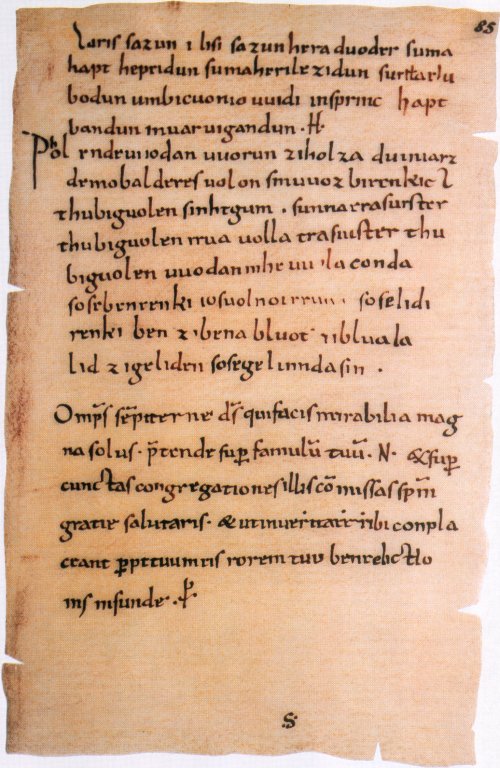

"In the

year 1842 a very extraordinary and very interesting

discovery was made at Merseberg: upon the spare leaf of

a MS. there were found two metrical spells in the

Old-German language: these upon examination were at once

recognized not only to be heathen in their character,

but even to contain the names of heathen gods, perfectly

free from the ordinary process of Christianization.

"The general character of

this poem is one well known to us: there are

many Anglo-Saxon spells of the same description.

What makes this valuable beyond all that have

ever been discovered, is the

number of genuine heathen names that survive in

it, which in others of the same kind have been

replaced by other sanctions; and which teach us

the true meaning of those which have survived in

the altered form. In a paper read before the

Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin, Grimm

identified Phol with Baldr, and this view he has

further developed in the new edition of his

Mythology. It is confirmatory of this view that

we possess the same spell in England, without

the heathendom, and where the place of the god

Baldr is occupied by that of our Lord himself.

The English version of the spell runs thus:

|

Dryhten rád,

fola slád;

se lihtode

and rihtode;

sette lið tý liðe

eic swa ban to bane,

sincwe to sinewe.

Hál wes ðú, on ðaes Hálgan Gástes naman!

|

The lord rade,

and the foal slade;

He lighted

and he righted;

set joint to joint

and bone to bone,

sinew to sinew.

Heal, in the Holy Ghost's name! |

"It will be admitted that this is something more

than a merely curious coincidence, and that it

leads to an induction of no little value. Now it

appears to me that we have reasonable ground to

believe our version quite as ancient and quite

as heathen as the German one which still retains

the heathen names, and that we have good right

to suppose that it once referred to the same

god.

"How then was this god named in England? Undoubtedly Pol

or Pal of such a god we have some obscure traces in

England. We may pass over the Appolyn and Apollo, whom

many of our early romancers number among the Saxon gods,

although the confused remembrance of an ancient and

genuine divinity may have lurked under this foreign

garb, and confine ourselves to the names of places

bearing signs of Pol or Pal. Grimm has shown that the

dikes called Phalgraben in Germany are much more likely

to have been originally Pfolgraben, and his conclusion

applies equally to Palgrave, two parishes in Norfolk and

Suffolk :—so Wodnes Dic, and the Devil's Dike between

Cambridge and Newmarket. Polebrooke in Northamptonshire,

Polesworth in Warwickshire, Polhampton in Hants,

Polstead in Suffolk, Polstead close under Wanborough

(Wodnesbeorh) in Surrey, —which is remarkable for the

exquisite beauty of its springs of water,—Polsden in

Hants, Polsdon in Surrev, seem all of the same class. To

these we must add Polsley and Pol thorn, which last name

would seem to connect the god with that particular tree:

last, but not least, we have in Poling, in Sussex, the

record of a race of Polingas, who may possibly have

carried up their genealogy to Baeldaeg in this form."

—John Kemble (1849).

"Baldr, gen. Baldrs, reappears in the OHG. proper

name Paltar (in Meichelbeck no. 450. 460. 611); and in

the AS. bealdor, baldor, signifying a lord, prince,

king, and seemingly used only with a gen. pl. before it:

gumena baldor, Cædm. 163, 4. wigena baldor, Jud. 132,

47. sinca bealdor, Beow. 4852. winia bealdor 5130. It is

remarkable that in the Cod. exon 276, 18 mæða bealdor

(virginum princeps) is said even of a maiden. I know of

only a few examples in the ON.: baldur î brynju, Sæm.

272b, and herbaldr 218b are used for a hero in general;

atgeirs baldr (lanceae vir), Fornm. sög. 5, 307. This

conversion from a proper name to a noun appellative

exactly reminds us of fráuja, frô, freá, and the ON.

týr. As bealdor is already extinct in AS. prose, our

proper name Paltar seems likewise to have died out

early; heathens songs in OHG may have known a paltar =

princeps. Such Gothic forms as Baldrs, gen. Baldris, and

baldrs (princeps), may fairly be assumed.

"This Baldrs would in strictness appear to have no

connexion with the Goth. balþs (bold, audax), nor Paltar

with the OHG. pald, nor Baldr with the ON. ballr

[[dangerous, dire]]. As a rule, the Gothic ld is

represented by ON. ld and OHG. lt: the Gothic lþ by ON.

ll and OHG. ld. But the OS. and AS. have ld in both

cases, and even in Gothic, ON. and OHG. a root will

sometimes appear in both forms in the same language; so

that a close connexion between balþs and Baldrs, pald

and Paltar, is possible after all. On mythological

grounds it is even probable: Balder's wife Nanna is also

the bold one, from nenna to dare; in Gothic she would

have been Nanþô from nanþjan, in OHG. Nandâ from

gi-nendan. The Baldr of the Edda may not distinguish

himself by bold deeds, but in Saxo he fights most

valiantly; and neither of these narratives pretends to

give a complete account of his life. Perhaps the Gothic

Balthae (Jornandes 5, 29) traced their origin to a

divine Balþ or Baldrs (see Suppl.).

"Yet even this meaning of the 'bold' god or hero might

be a later one: the Lith. baltas and Lett. balts signify

the white, the good; and by the doctrine of

consonant-change, baltas exactly answers to the Goth.

balþs and OHG. pald. Add to this, that the AS.

genealogies call Wôden's son not Bealdor, Baldor, but

Bældæg, Beldeg, which would lead us to expect an OHG.

Paltac, a form that I confess I have nowhere read. But

both dialects have plenty of other proper names

compounded with dæg and tac: OHG. Adaltac, Alptac,

Ingatac, Kêrtac, Helmtac, Hruodtac, Regintac, Sigitac;

OS. Alacdag, Alfdag (Albdag, Pertz 1, 286), Hildidag,

Liuddag, Osdag, Wulfdag; AS. Wegdæg, Swefdæg; even the

ON. has the name Svipdagr. Now, either Bældæg simply

stands for Bealdor, and is synonymous with it (as e.g.,

Regintac with Reginari Sigitac with Sigar, Sigheri); or

else we must recognise in the word dæg, dag, tac itself

a personification, such as we found another root

undergoing (p. 194-5) in the words div, divan, dina,

dies; and both alike would express a shining one, a

white one, a god. Prefixing to this the Slavic bièl,

bèl, we have no need to take Bældæg as standing for

Bealdor or anything else, Bæl-dæg itself is white-god,

light-god, he that shines as sky and light and day, the

kindly Bièlbôgh, Bèlbôgh of the Slav system (see

Suppl.). It is in perfect accord with this explanation

of Bæl-dæg, that the AS. tale of ancestry assigns to him

a son Brond, of whom the Edda is silent, brond, brand,

ON. brandr [[fire brand or blade of a sword]],

signifying jubar, fax, titio. Bældæg therefore, as

regards his name, would agree with Berhta, the bright

goddess.

"...So much the more valuable are the revelations of

the Merseburg discovery; not only are we fully assured

now of a divine Balder in Germany, but there emerges

again a long-forgotten mythus, and with it a new name

unknown even to the North.

"When, says the lay, Phol (Balder) and Wodan were one

day riding in the forest, one foot of Balder's foal,

'demo Balderes volon,' was wretched out of joint,

whereupon the heavenly habitants bestowed their best

pains on setting it right again, but neither Sinngund

and Sunna, nor yet Frûa and Folla could do any good,

only Wodan the wizard himself could conjure and heal the

limb (see Suppl.).

"The whole incident is as little known to the Edda as to

other Norse legends. Yet what was told in a heathen

spell in Thuringia before the tenth century is still in

its substance found lurking in conjuring formulas known

to the country folk of Scotland and Denmark (conf. ch.

XXXVIII, Dislocation), except that they apply to Jesus

what the heathens believed of Balder and Wodan.

"...The horse of Balder, lamed and checked on his

journey, acquired a full meaning the moment we think of

him as the god of light or day, whose stoppage and

detention must give rise to serious mischief on the

earth. Probably the story in its context could have

informed us of this; it was foreign to the purpose of

the conjuring spell.

"The names of the four goddesses will be discussed in

their proper place; what concerns us here is, that

Balder is called a second and hitherto unheard-of name,

Phol. The eye for our antiquities often merely wants

opening: a noticing of the unnoticed has resulted in

clear footprints of such a god being brought to our

hand, in several names of places.

"In Bavaria there was a Pholesauwa, Pholesouwa, ten or

twelve miles from Passau, which the Traditiones

patavienses first mention in a document drawn up between

774 and 788 (MB. vol 28, pars 2, p. 21, no. 23), and

afterwards many later ones of the same district: it is

the present village of Pfalsau. Its composition with aue

quite fits in with the suppostion of an old heathen

worship. The gods were worshipped not only on mountains,

but on 'eas' inclosed by brooks and rivers, where

fertile meadow yielded pasture, and forest shade. Such

was the castum nemus of Nerthus in an insula Oceani,

such Fosetesland with its willows and well-springs, of

which more presently. Baldrshagi (Balderi pascuum),

mentioned in the Friðþiofssaga, was an enclosed

sanctuary (griðastaðr), which none might damage. I find

also that convents, for which time-hallowed venerable

sites were preferred, were often situated in 'eas'; and

of one nunnery the very word used: 'in der megde ouwe,'

in the maids' ea (Diut. 1, 357). The

ON. mythology supplies us with several eas named after

the loftiest gods: Oðinsey (Odensee) in Fünen, another

Oðinsey (Onsöe) in Norway, Fornm. sög. 12, 33, and

Thôrsey, 7, 234. 9, 17; Hlêssey (Lässöe) in the

Kattegat, &c., &c. We do not know any OHG. Wuotanesouwa,

Donarsouwa, but Pholesouwa is equally to the point."

— Jakob Grimm (1844).

|

"Of the names occurring in this strophe Uodan-Odin,

Baldur, Sunna (synonym of Sol - Alvíssmál 16; Prose Edda

- Nafnaþulur), Friia-Frigg, and Volla-Fulla are well

known in the Icelandic mythic records. Only Phol and

Sinhtgunt are strangers to our mythologists, though

Phol-Falr surely ought not to be so.

In regard to the German form Phol, we find that it has

by its side the form Fal in German names of places

connected with fountains. Jakob Grimm has pointed out a

"Pholes" fountain in Thuringia, a "Fals" fountain in the

Frankish Steigerwald, and in this connection a "Baldur"

well in Reinphaltz.1 In the Danish popular traditions

Baldur's horse had the ability to produce fountains by

tramping on the ground, and Baldur's fountain in Seeland

is said to have originated in this manner (cp. P. E.

Muller2 on Saxo, Hist., 120). In Saxo, too, Baldur gives

rise to wells (Victor Balderus, ut afflictum siti

militem opportuni liquoris beneficio recrearet, novos

humi latices terram altius rimatus operuit - Book 3).

...This very circumstance seems to indicate that Phol,

Fal, was a common epithet or surname of Baldur in

Germany, and it must be admitted that this meaning must

have appeared to the German mythologists to be confirmed

by the Second Merseburg Charm; for in this way alone

could it be explained in a simple and natural manner,

that Baldur is not named in the first line as Odin's

companion, although he actually attends Odin, and

although the misfortune that befalls "Baldur's foal" is

the chief subject of the narrative, while Phol on the

other hand is not mentioned again in the whole formula,

although he is named in the first line as Odin's

companion.

This simple and incontrovertible conclusion, that Phol

and Baldur in the Second Merseburg Charm are identical

is put beyond all doubt by a more thorough examination

of the Norse records. In these it is demonstrated that

the name Falr was also known in the North as an epithet

of Baldur.

"...Their identity is furthermore confirmed by the

fact that Baldur in early Christian times was made a

historical king of Westphalia. The statement concerning

this, taken from Anglo-Saxon or German sources, has

entered into the foreword to Gylfaginning. Nearly all

lands and peoples have, according to the belief of that

time, received their names from ancient chiefs. The

Franks were said to be named after one Francio, the East

Goth after Ostrogotha, the Angles after Angul, Denmark

after Dan, etc. The name Phalia, Westphalia, was

explained in the same manner, and as Baldur's name was

Phol, Fal, this name of his gave rise to the name of the

country in question. For the same reason the German poem

Biterolf makes Baldur (Paltram) into king ze Pülle.

(Compare the local name Pölde, which, according to J.

Grimm, is found in old manuscripts written Polidi and

Pholidi.) In the one source Baldur is made a king in

Pholidi, since Phol is a name of Baldur, and in the

other source he is for the same reason made a king in

Westphalia, since Phal is a variation of Phol, and

likewise designated Baldur.

"The misfortune which happened first to Baldur and

then to Baldur's horse must be counted among the

warnings which foreboded the death of the son of Odin.11

There are also other passages which indicate that

Baldur's horse must have had a conspicuous signification

in the mythology, and the tradition concerning Baldur as

rider is preserved not only in northern sources

(Lokasenna 28, Gylfaginning), and in the Second

Merseburg Charm, but also in the German poetry of the

Middle Ages. That there was some witchcraft connected

with this misfortune which happened to Baldur's horse is

evident from the fact that the galdur songs sung by the

goddesses accompanying him availed nothing. According to

the Norse ancient records, the women particularly

exercize the healing art of galdur (compare Gróa and

Sigurdrífa), but still Odin has the profoundest

knowledge of the secrets of this art; he is galdurs

faðir (Vegtamskviða 3). And so Odin comes in this

instance, and is successful after the goddesses have

tried in vain. We must fancy that the goddesses make

haste to render assistance in the order in which they

ride in relation to Baldur, for the event would lose its

seriousness if we should conceive Odin as being very

near to Baldur from the beginning, but postponing his

activity in order to shine afterwards with all the

greater magic power, which nobody disputed.

"The goddesses constitute two pairs of sisters:

Sinhtgunt and her sister Sunna, and Frigg and her sister

Fulla. According to the Norse sources, Frigg is Baldur's

mother. According to the same records, Fulla is always

near Frigg, enjoys her whole confidence, and wears a

diadem as a token of her high rank among the goddesses.

12 An explanation of this is furnished by the Second

Merseburg Charm, which informs us that Fulla is Frigg's

sister, and so a sister of Baldur's mother. And as Odin

is Baldur's father, we find in the Second Merseburg

Charm the Baldur of the Norse records, surrounded by the

kindred assigned to him in these records.

"Under such circumstances it would be strange,

indeed, if Sinhtgunt and the sun-dis, Sunna, did not

also belong to the kin of the sun-god, Baldur, as they

not only take part in this excursion of the Baldur

family, but are also described as those nearest to him,

and as the first who give him assistance.

"The Norse records have given to Baldur as wife Nanna,

daughter of that divinity which under Odin's supremacy

is the ward of the atmosphere and the owner of the

moon-ship. If the continental Teutons in their

mythological conceptions also gave Baldur a wife devoted

and faithful as Nanna, then it would be in the highest

degree improbable that the Second Merseburg Charm should

not let her be one of those who, as a body-guard, attend

Baldur on his expedition to the forest. Besides Frigg

and Fulla, there are two goddesses who accompany Baldur.

One of them is a sun-dis, as is evident from the name

Sunna; the other, Sinhtgunt, is, according to Bugge's

discriminating interpretation of this epithet, the dis

"who night after night has to battle her way." A goddess

who is the sister of the sun-dis, but who not in the

daytime but in the night has to battle on her journey

across the sky, must be a goddess of the moon, a

moon-dis. This moon-goddess is the one who is nearest at

hand to bring assistance to Baldur. Thus she can be none

else than Nanna, who we know is the daughter of the

owner of the moon-ship. The fact that she has to battle

her way across the sky is explained by the Norse mythic

statement, according to which the wolf-giant Hati is

greedy to capture the moon, and finally secures it as

his prey (Völuspá, Gylfaginning).

"...The name Nanna (from the verb nenna; cp.

Vigfusson's Dictionary, Lexicon Poeticum) means "the

brave one." With her husband she has fought the battles

of light, and in the Norse, as in the Germanic,

mythology, she was with all her tenderness a heroine."

—Viktor Rydberg (1882)

Vigfusson defines nenna as "to strive, to travel" and

Egilsson as udøve med kraft og raskhed "to strive with

force and speed." The connection between Nanna and nenna

was first made by Grimm in DM Vol. I, Ch. 11: "On

mythological grounds it is even probable: Baldur's wife

Nanna is also the bold one from nenna, to dare." Jan De

Vries relates it to the Germanic root nanþ-, giving the

meaning "the daring one." (Altergermanishe

Religiongeschichte, Berlin 1970).

|