THE SEVEN SAXON GODS

Based on the Names of the Days of the Week in

A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence in Antiquities

1628 Edition

Also see Derivative Works from this collection below.

[HOME] [POPULAR RETELLINGS]

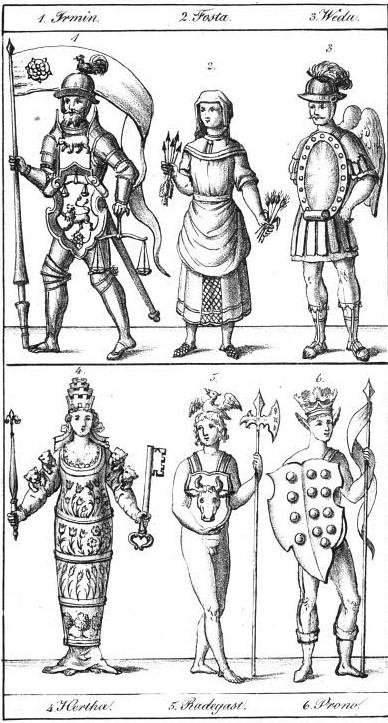

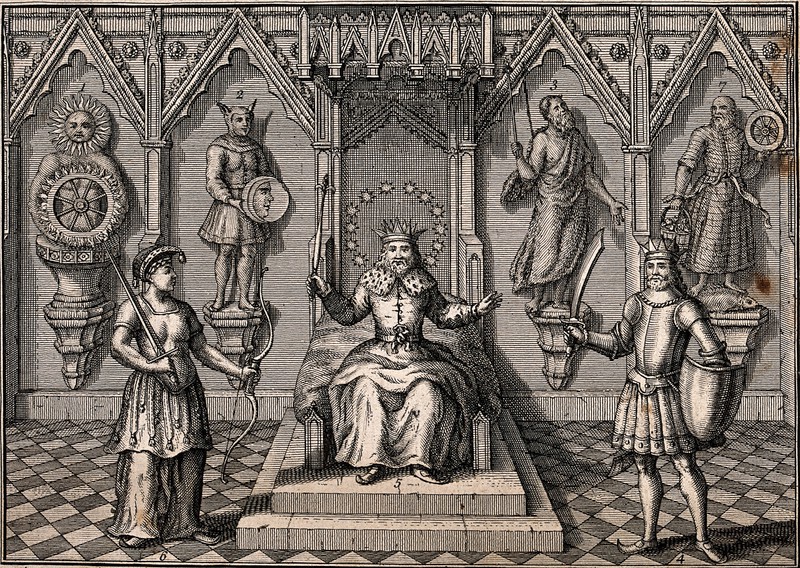

Richard Verstegan, a Catholic goldsmith and engraver of Dutch descent, published a full-length account of British history in which he devoted a chapter to Saxon paganism, illustrated with images of the first collection "Saxon" deities, engraved by Verstegan himself. His work is the first to codify the Germanic gods who gave their names to the days of the English week. All of the figures have artistic prerequisites, but are gathered together here for the first time as a pantheon. Vestegan's collection predates the discovery of the Codex Regius manuscript in 1643. The author appears to have no knowledge of Snorri's Edda, instead relying on the histories penned by Tacitus, Saxo Gramaticus, the Venerable Bede, Adam of Bremen and Olaus Magnus for information.

This set of so-called Saxon Gods established a parallel, but separate, stream of artistic inspiration for depictions of the Germanic gods, distinct from those directly (or indirectly) inspired by the Eddas. In contrast, these images are based on historic accounts, which predate the discovery of the Poetic Edda in 1643. In other words, two distinct sources of inspiration for visual representations of the Germanic gods existed side-by-side throughout much of the modern era, until the imagery of the "Saxon" Gods, died out in the early part of the 20th century. A full catalog of derivative works is included below, illustrating the origin, history and ultimate demise of this stream of artistic inspiration.

|

Richard

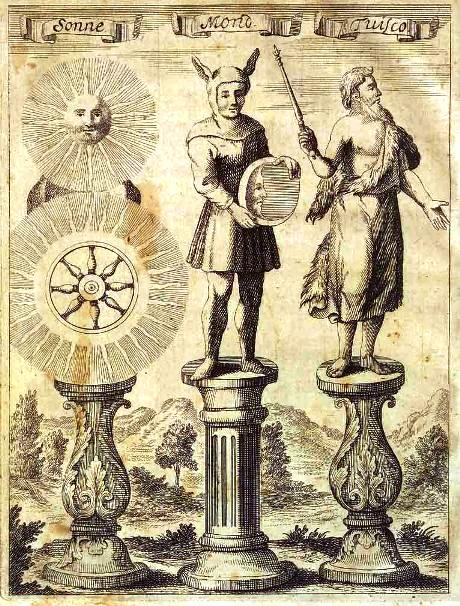

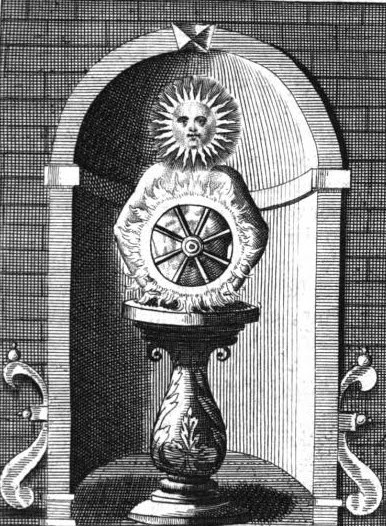

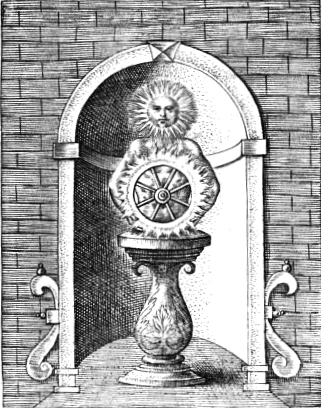

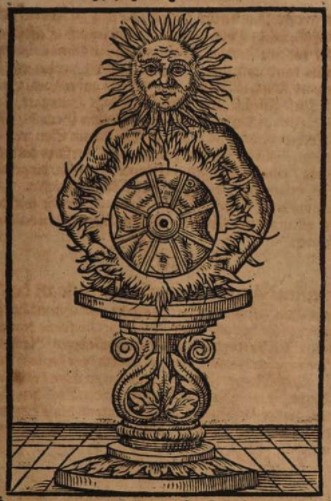

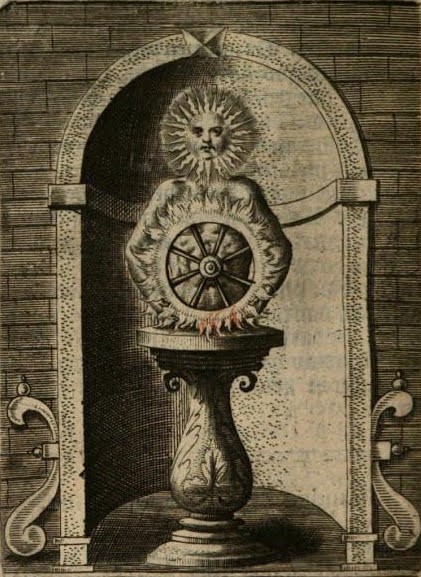

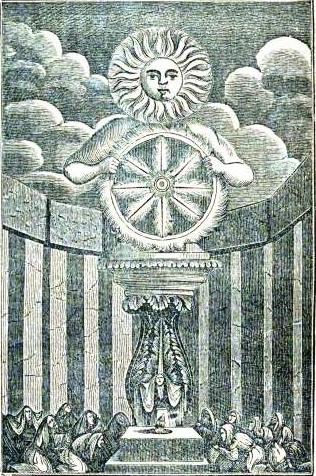

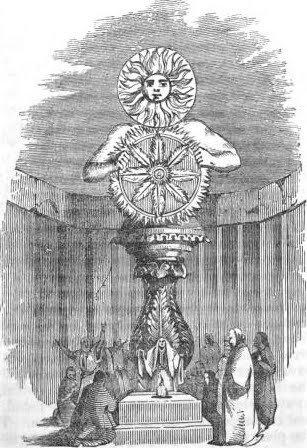

Vertigan's Gods of the Days of the Week with accompanying text  The Idoll of the Sun Sunday |

||

| It was made as here appeareth, Iike halfe a naked man, set upon a Piller, his face as it were, brightened with gleames of fire, and holding with both his armes stretched out, a burning wheele upon his breast: the wheele being to signifie the course which he runneth round about the world; and the fiery gleames, and brightnes, the light, and heat wherewith he warmeth, and comforteth the things, that live, and grow. | ||

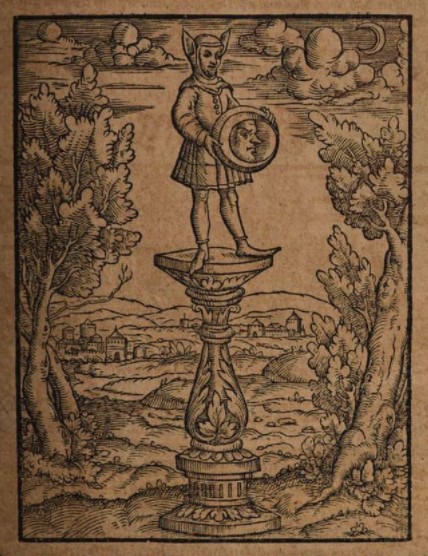

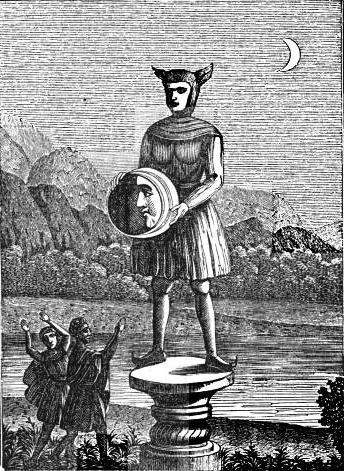

The Idoll of the Moone Monday |

||

| The forme of this Idoll seemeth very strange, and ridiculous, for being made for a woman shee hath a short coat like a man: but more strange it is to see her hood with such two long eares. The holding of a Moone before her breast may seeme to have beene to expresse what she is, but the reason of her chapron with long eares, as also of her short coat, and pyked shooes, I doe not finde. | ||

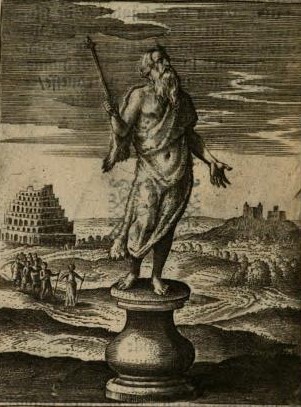

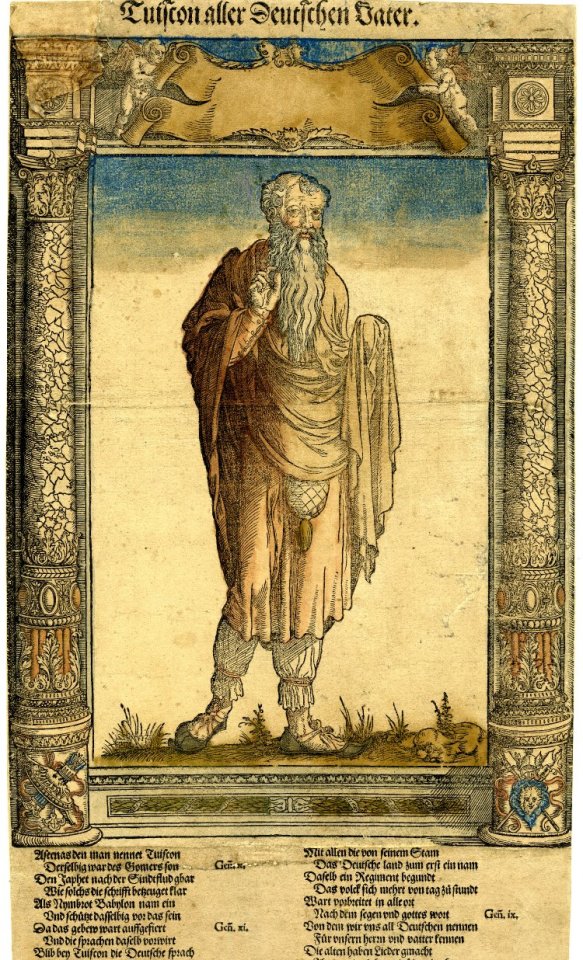

The Idoll of Tuysco Tuesday |

||

|

The next unto the Idols of the two most apparant Planets, was

the Idoll of Tuysco: the most antient, and peculiar god of all

the Germans, here described in his garment of a skinne,

according to the most antient manner of the Germans cloathing. Of this Tuisco, the firsthand, and chiefest man of name among the Germans, and after whom they doe call themselves Tuytshen, that is, duytshes, or duytsh-people, I have already spoken in the first Chapter: as also shewed, how the day which yet amongst us retaineth the name of Tuisday, was especially dedicated unto the adoration, and service of this Idoll.* *Tyr was not associated with Tuesday until at least 1670 in De Anglorum gentis origine by Robert Sheringham, who forcefully refuted Verstegan's identification of Tuesday with Tuisco from Tacitus' Germania. |

||

The Idoll Woden Wednesday |

||

|

The next was the Idoll Woden, who as by his Picture here set

downe appeareth was made armed, and among our Saxon Ancestors

esteemed, and honoured for their god of Battell, according as

the Romans reputed, and honoured their god Mars.

He was while sometime he lived amongst them, a most valiant and victorious Prince, and Captaine, and his Idoll was after his death honoured, prayed, and sacrificed unto, that by his ayd, and furtherance they might obtaine victory over their enemies: which when they had obtained, they sacrificed unto him such prisoners as in battell they had taken. The name WODEN signifies fires, or furious, and in like sence we yet retaine it, saying when one is in a great rage that he is WOOD or taketh And after this Idoll, we doe yet call that day of the weeke WEDENSDAY, in steed of WODENSDAY upon which he was chiefly honoured, Venerable Bede nameth one WODEN, to have beene the great Grandfather of HINGISTUS, that first came with the Saxons into Brittaine, but this seemeth to have beene another Prince of the same name; and not he whose Idoll is here spoken of, who in much likelyhood was long before the great Grandfather of Hingistus. |

||

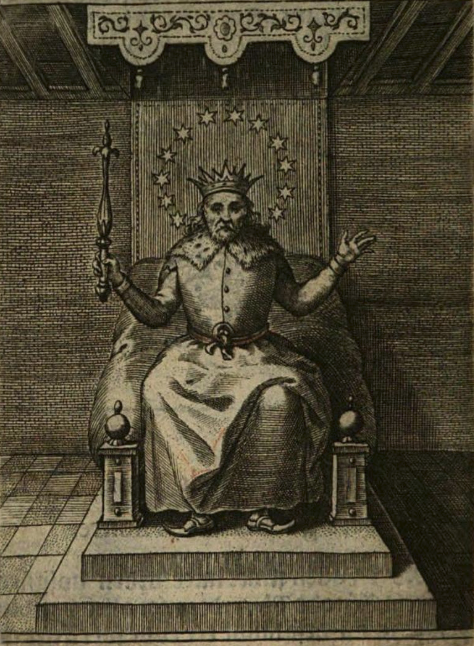

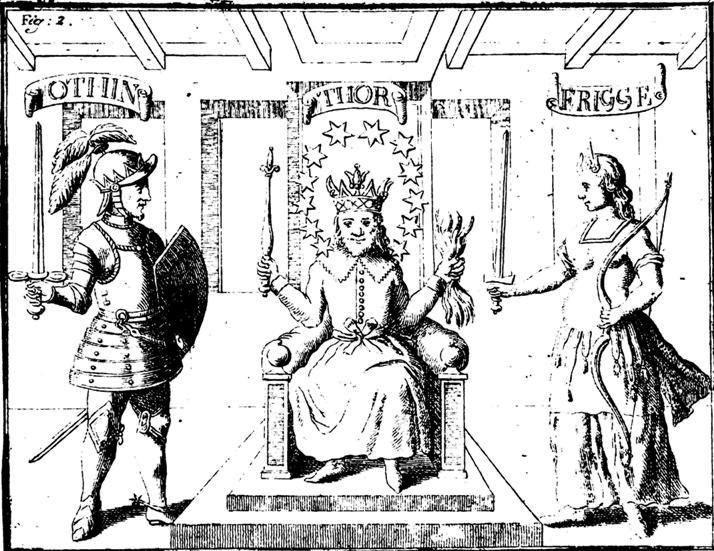

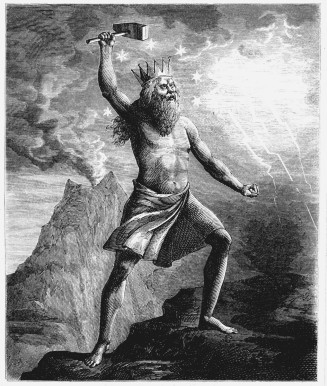

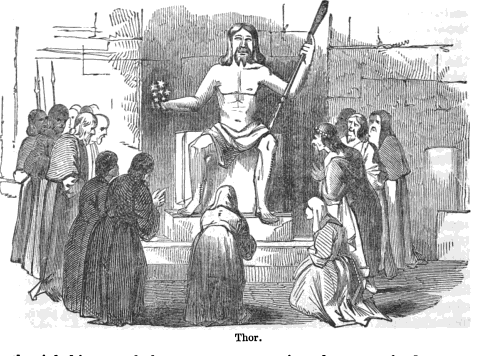

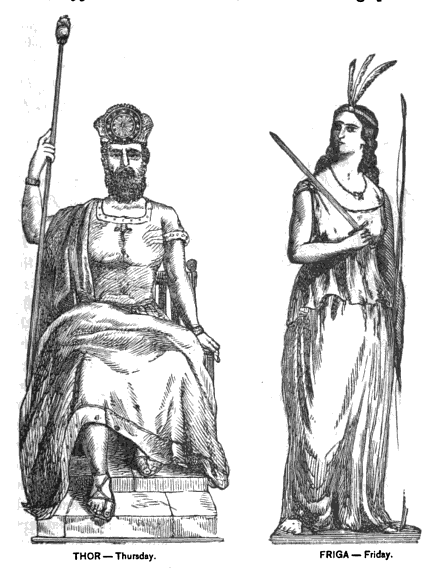

The Idoll Thor Thursday |

||

|

The next in order as aforesayd, was the Idoll THOR, who was not

onely served, and sacrificed unto of the antient Pagan-Saxons,

but of all the

Teutonicke

people of the septentrionall Regions, yea,

even of the people that dwelt beyond Thule or ISLAND, for in

Greeneland was he knowne, and adored; in memory whereof a

promont dryor high poynt of land lying out into the sea, as also

a river which felleth into the sea at the said promontory, doth

yet beare his name; and the manner how he was made, his picture

here doth declare. This great reputed God, being of more estimation than many of the rest of like sort, though of as little worth as any of the meanest of that rabble; was majestically placed in a very large, and spacious Hall, and there set, as if he had reposed himselfe upon a covered Bed. On his head he wore a Crowne of gold, and round incompasse above, and about the same, were set or fixed, twelve bright burnished golden starres. And in his right hand he held a Kingly Scepter. He was of the seduced Pagans beleeved to be of most maruelous power, and might, yea, and that there were no people through out the whole World, that were not subjected unto him; and did not owe him Divine honour, and seruice. That there was no puissance comparable to his: his Dominion of all others most farthest extending it selfe, both in Heaven, and Earth. That in the Aire he governed the Winds, and the Cloudes and being displeased did cause lightning, thunder, and tempests, with excessiue Raine, Haile, and all ill weather. But being well pleased, by the adoration,sacrifice,and seruice of his suppliants, he then bestowed upon them most faire, and seasonable weather: and caused Corne aboundantly to growe as also all sorts of fruites, &c. and kept away from them the Plague, and all other evill, and infectious diseases. Of the weekly day which was dedicated unto his. peculiar seruice, we yet retaine the name of THURSDAY, the which the Danes, and Swedians doe yet call THORS-DAY. In the Netherlands, it is called DUNDER-DAGH, which being written according to our English orthography, is THUNDERS-DAY, whereby it may appeare that they antiently therein intended, the day of the the god of THUNDER; and in some of our old Saxon bookes I find it to have beene written THUNRES DEAG. So as it seemeth that the name of THOR was abteviated of THUNRE, which we now write THUNDER. |

||

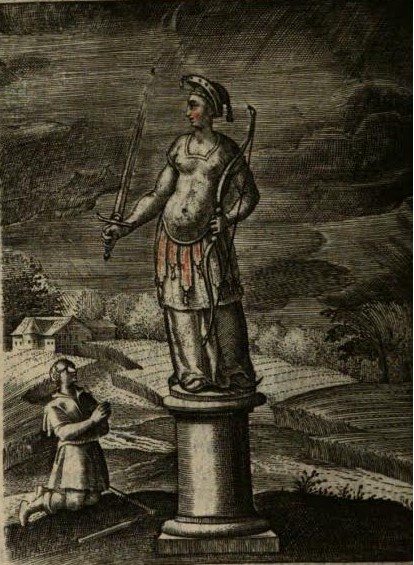

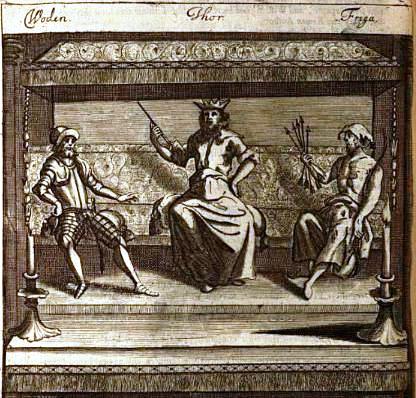

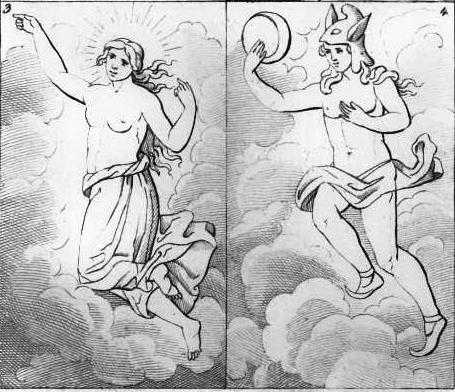

The Idoll Friga Friday |

||

|

The next following in rank and reputation, was the Goddess

Friga, who was made according as this picture here doth

demonstrate. This Idoll represented both sexes, as well man as woman, and as an Hemophrodite is said to have had both the members of a man, and the members of a woman. In her right hand she held a drawne Sword, and in her left a Bow signifying thereby that women as well as men should in time of neede be ready to fight. Some honoured her for a God and some for a Goddess, but she was ordinarily taken rather for a Goddesse than a God, and was reputed the giver of peace, and plenty, as also the causer, and maker of love, and amity, and of the day. Of her especiall adoration we yet retaine the name of Friday, and as in the order of the dayes of the weeke THURSDAY commeth betweene Wednesday and Friday, so (as Olaus magus noteth) in the septentrionall regions, where they made the Idoll THOR sitting or lying in a great Hall upon a covered bed, they also placed on the one side of him the Idoll WODEN, and on the other side the Idoll FRIGA. Some do call her frea and not friga., and say she was the wife of Woden, but she was called FRIGA, and her day our Saxon ancestors called FRIGE DEAG, from whence our name now of Friday in deed commeth, Saxo Gramaticus saith, that the people which by reason of the great famine in the time of Snio King of Denmarke (whereof I have before made mention) were constrained by lot to go seeke them new habitations, were by the Goddess FRIGA commanded to call themselves Longobards, which is an opinion by Crantziuts and others rejected as fabulous, and for no lesse I esteeme it. |

||

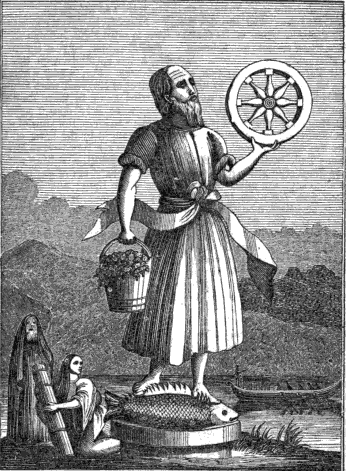

The Idol Seater Saturday |

||

|

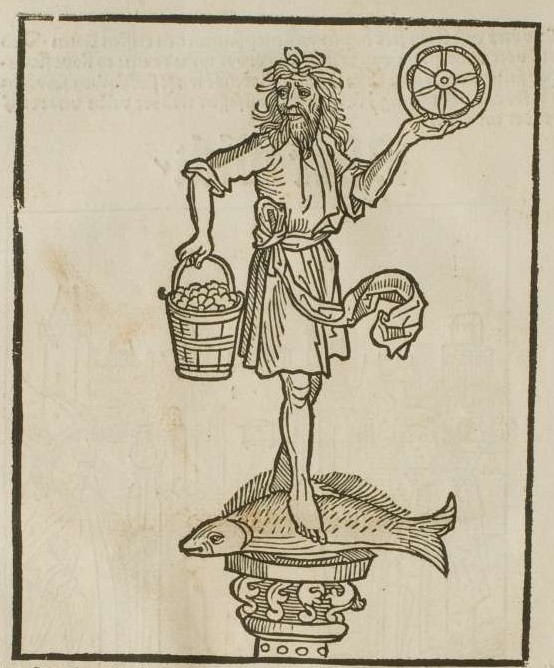

The last to make up here number of seven, was the Idoll SEATER,

fondly of some supposed to be Saturnus, for he was otherwise

called CRODO, this goodly god stood to be adored in such manner

as here this picture doth shew him.

First on a pillar was placed a pearch, on the sharpe prickled backe whereof stood this Idoll. He was leane of visage, having long haire, and a long beard: and was bare-headed, and bare footed. In his left hand he held up a wheele, and in his right he carried a paile of water, wherein were flowers, and fruites. His long coate was girded unto him with a towel of white linnen. His standing on the sharpe finnes of this fishe was to signifie that the Saxons for their serving him, should pass stedfastly, & without harme in dangerous, and difficult places. By the wheele was betokened the knit unity, and conjoyned concord of the Saxons, and their concurring together in the running one course. By the girdle which with the wind streamed from him was signified the Saxons freedome. By the paile with flowers, and fruits was declared that with kindly raine he would nourish the Earth, to bring foorth such fruites, and flowers. And the day unto Name unto which he yet give the name of SATER-DAY, did first receive by being unto him celebrated, the same appellation. |

||

The Moon and Seater, the Idol of Saturday

are based on images which first appeared in

Conrad Bote's Saxon Chronicle, 1492.

Moon (barefoot) |

Krodo, later Seater |

"Bote's Saxon Chronicle, under the year 780, relates that King Charles, during his conquest of the East Saxons on the Hartesburg, overthrew an idol similar to Saturn, which the people called Krodo."

The one-handed god Týr, was not known to modern scholars until the first modern printing of Snorri's Edda, re-edited and published as a book of fables in the 1590s. Verstegan's work, first published in 1605, shows no sign of knowledge of that text. |

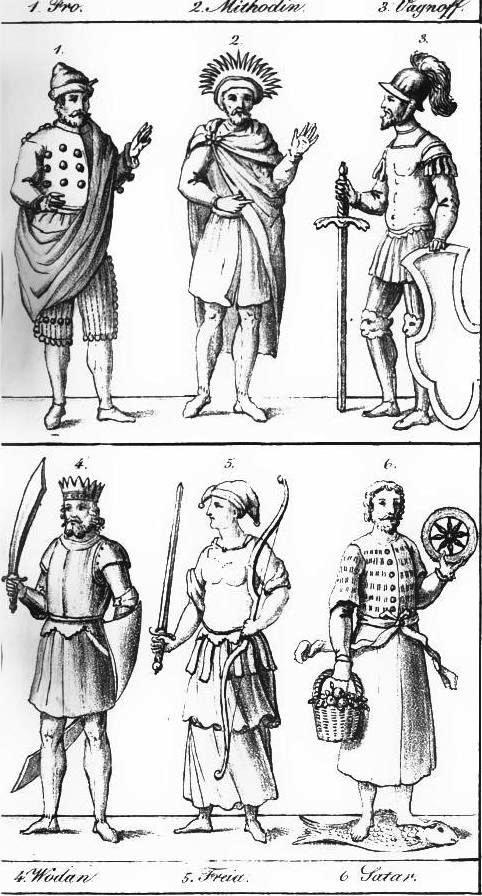

Tuscion, the Father of All Germans The First Twelve Old Kings and Monarchs of the German Nation by Nikolaus Stör & Peter Flötner |

Tuiscon, Father of Mannus Chronica des Uralten Haus Bayern und der alten Deutschen by Johannes Aventinus |

(who lend their names to Friday, Wednesday and Thursday respectively)

are based on a woodcut from Olaus Magnus' A Description of the Northern Peoples, published in 1555.

Sun and Moon first appear together in Johannes Pomarius'

Chronika der Sachsen und Niedersachsen, 1588.

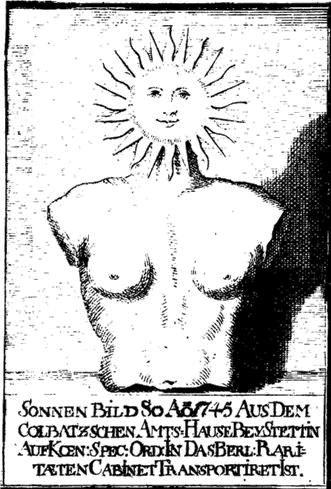

Sun |

Moon (with shoes) |

Richard Verstegan's 1605 book provides us a summary of what was known about the Norse gods prior to the discovery of the Eddas, and a glimpse of what our knowledge of them might have looked like today without those important source documents. It is the last roster of the Germanic gods before the rise and rapid spread of modern Eddic scholarship. Note that Thor does not yet wield his characteristic hammer and appears enthroned like a Germanic Jupiter, Odin appears in armor, and Frigg carries a sword. These primitive portraits are based on limited historic accounts of the gods, independent of Eddic lore, which would not become widely disseminated until the last quarter of the 18th century— around the time of the American Revolution. It would not be until 1865, during the American Civil War, that a full translation of the Poetic Edda would be published in English. As knowledge of the Eddas spread, the tradition of the Gods of the Days of the Week began to fade, beginning around the end of the 19th century (possibly coinciding with the rise of Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle of Operas, beginning in 1876) and finally dying around 1920.

BEFORE THE RECOVERY OF THE EDDAS

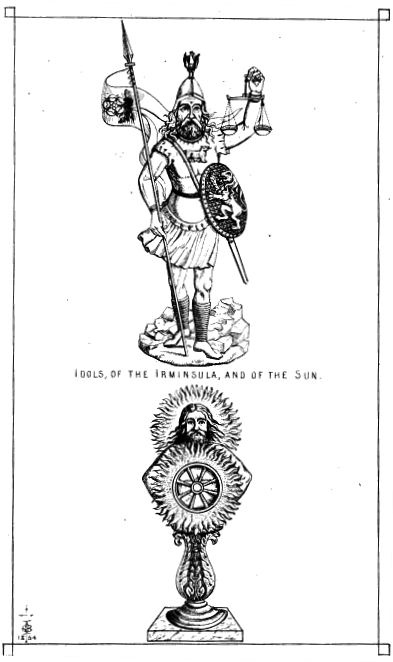

Ermensewl [Irminsul]

The Saxons had besides these the Idol ERMENSEWL in great reputation, his name of ERMENSEWL or ERMESEWL being as much as to say, as the Piller or stay of the poore. This god (or more truely Divell) was made armed,standing among flowers. In his right hand he held a staffe having at it a banner wherein was. painted a read Rose. In his other band he held a paire of ballance, and upon his head was placed a Cocke. On his brest was carved a Beare, and before his middle was fixed a scutcheon, in chiefe whereof was also a paire of ballance, in face a Lion, and in point a Rose: and this Idoll the Saxons and the other Germans as well as the Saxons did also serue, and adore. And whereas Tacitus saith, that of all the Gods the Germans especially honored Mercury find upon certaine dayes offered men unto him in sacrifice, this Idoll ERMENSEWL is of divers taken to be the same that the Romans interpreted tot Mercury, though some others have interpreted him for Mars, and WODEN with less reasone for Mercury; for that he was held of the Saxons for their God of warre, as Mercury among the Romans never was.

And in all likelihood of truth, the Romans for some property which the Germans ascribed to their Idols, might well for the like property ascribed by them unto theirs, take them to bee the very same Idols, albeit they were of the Germans called by other names, and made in other manner. And so in like sort hath THOR been of some interpreted for Iupiter, for that among his other marvels he made, and caused, thunder, and was chiefly honoured upon the same day whereon the Romans honoured their Iupiter. FRIGA is also interpreted for Venus because among other her qualities she was a furtherer of friendship, and that on the very day of her chiefe celebration, the Romans chiefly honoured their amiable Venus. SEATER alias CRODO was also mistaken for Saturnus, not in regard of any saturnicall quality, but because his name founded somewhat neere it, and his festivall day fell jump with that of Saturne. But I can finde no reason to thinke that any of these were indeed intended for such, before it pleased the Romans to interpret them so, and perhaps some of the Germans for their Idols more honour, were afterward content to allow it so.

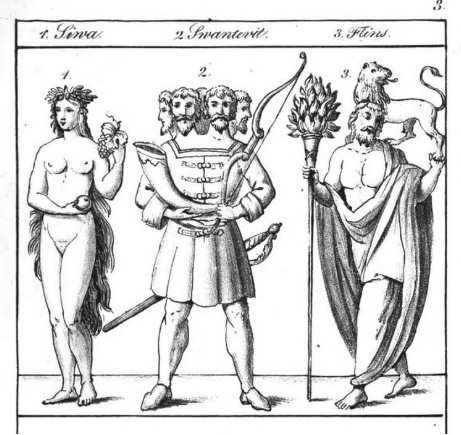

They adored also the Idoll FLYNT, who had that name for his being set upon a great Flint stone.This idoll was made like the Image of death, and naked, save onely a sheete about him. In his right hand he held a torch, or as they termed it, a fire blase. On his head a Lyon rested his two fore-feet, standing with the one of his hinder feet upon his left shoulder, and with the other in his hand; which to support, he lifted up as high as his shoulder. They had also, HELMSTEED, PRONO, FIDGAST, SIWE, and many others which would be too long, and too worthlesse, hereto be described.

adds the following deities to the ranks of the so-called Saxon Gods:

The appellations of two other Saxon Goddesses have been transmitted to us in the pages of Bede; namely, Rheda, who gave her name to March—Rhedmonath,—because therein they sacrificed to her; and Eoster, who in like manner, and for the same reason, gave her name to April,—Eostre-monath; from which no doubt has come our term of Easter, applied to the season of the great Paschal solemnities.

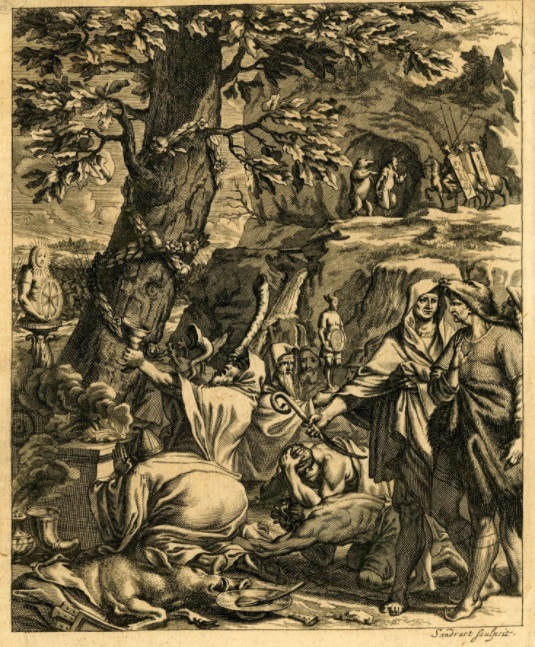

The Angles,—and it should be recollected that they exercised a powerful influence in the formation of the compound Anglo-Saxon character—had also a goddess called Ertha*, or the Earth, as we learn from Tacitus.—

"The tribes in common worship the Goddess, Ertha, that is, the Mother Earth,—believing that she interposes in human affairs, and is car-borne to the people. In an island of the ocean there is an untrodden grove, wherein is a consecrated car, enveloped in a veil. This the priest alone is permitted to approach. He perceives the goddess enter the vehicle, which is drawn by cows, and follows her with much devotion. Then the days are festive, and those places rejoice which she honours with her visit and residence. They now enter into no wars, nor take up arms, but every sword is sheathed; both abroad and at home only peace is known, only peace is in estimation, till the same priest restores the goddess to the temple, satiated with mortal converse.Then the car and the clothes, and, if you will believe it, the goddess herself, are washed in a secret lake. Slaves attend, whom the same lake immediately swallows up. Hence arises a mysterious dread, and a holy ignorance as to what that can be which is seen only by those who are about to perish."

was first argued by Jacob Grimm in his Teutonic Mythology, and most recently by John McKinnell in the early 21st century.

*Tacitus' Germania has been known to modern scholars since 1525, when it was first rediscovered and recognized. Ertha, "Earth" is an early textual reading error by German scholars for "Nerthum", now considered to be the best reading of the available manuscripts. The case for the reading Nerthum (neuter form of the name Nerthus)

One great object of fear with the Saxons was the evil being whom they called Foul, a name which occurs in their form of exorcism against the bite of serpents. Beyond this we know nothing of him, and perhaps, after all, the word, Foul, may not have been used as applicable to an individual, but to the foul, or evil, spirits in general. Flinn, or Flint, and Zernebock, are also mentioned by some writers as being amongst their evil deities, whose influence was to be propitiated by prayer and sacrifice. The first is described by Verstegan as an idol, who had that name from his being set on a great flint stone. This idol was made like the image of death, and naked save only a sheet about him. In his right hand he held a torch, or, as they term it, a fire-blase. On his head a lion rested his two fore-feet, standing with the one of his hinder feet upon his left shoulder, and with the other in his hand; which to support he lifted up as high as his shoulder.

Zernebock, that is the block, or malevolent deity, seems more particularly to have been the devil of the Anglo-Saxons. He was sometimes simply termed the Black, or as it is translated in the Latin chronicles, Ater, that colour seeming to be inseparable from the popular ideas of the demon. He would indeed appear to have been the symbol of night or darkness, as Juterbag played the opposite part of the classical Aurora. Siba, Seba, or Sjeba, was represented in the shape of a beautiful woman, her heir falling down below her knees, her hands behind her, and in one a golden apple, while the other held a bunch of grapes with a golden leaf.

A deity called Crodo, or Crodus, is mentioned by several writers. Albinus, in his Novce Saxonum Historiue Progymnasmata, thus describes him :

"Crodus is an old man, in the form of a reaper, standing with naked feet upon a little fish, called a perch. He was clad in a white tunic, with a linen girdle, in his left handa wheel, in his right a small vessel filled with water in which floated roses and every sort of garden-fruit. The picture is in the Brunswick Chronicle."

The Irmensul, or Irmensul, Hermessul, or Armessul, has found so many different interpretations, as well as modes of spelling, that it is hard to say what it precisely was. Grimm in his invaluable Deutsche Mythologie tells us that it meant the "universal column," the sustainer, namely, of all things, and closely connected with the Ydrasil of the Scandinavians. Albinus in his Meisnic Chronicles says it might have meant the pillar of Arminius—the leader who defeated the Romans—; or the pillar of Hermes, that is, Mercury; or the pillar supporting the poor and feeble. The Saxon Chronicle describes it as representing Mars, in the shape of an armed man, who stands in a green field, up to his middle in flowers, and girded with a sword. In his right hand he has a flag on which is a rose or wild-flower; in his left a scale; on his helmet, a weathercock; on his shield a lion, above which is a scale, and below it a rose; and some add that upon his breast was a bear.

But whatever the Irminsula may have been intended to represent, it was the most celebrated idol in all Saxony, and its picture found a place in many temples. The fane of the great image was at Marsberg, or Mersberg. It stood upon a column about eleven feet high, composed of light red marble, with belts of orichalcus, the upper and lower gilt, as was the one between these and the crown,—also gilt;—so too was the upper circle incumbent upon it, with three heroic verses. The base was of a rude gravelstone; the whole being surrounded with an iron railing to keep it sacred from the multitude, or to save it from injury. The idol itself was of wood, and about it were three other figures. The Irminsala was served both by priests and priestesses, who acquired no little dignity and influence from the votaries of so honoured a deity. The woman pretended to fortune-telling and divination. The man performed the sacrifices, and had besides considerable influence in political affairs, their sanction being held essential to success. They moreover appointed the district governors of continental Saxony, and named the judges who annually decided whatever disputes might occur in the provinces. When the day of battle came, they took the idol down from its pillar, and carried it to the field in hopes by its presence to secure victory to their people. The conflict being over, they then immolated to it war-prisoners, and such of their own army as had proved cowards. When Charlemagne had defeated the Saxons, he broke the idol, and demolished its temple, a pious work which occupied one part of his army for three days while the other stood by under arms to prevent its worshippers from coming to the rescue. The column was flung into a waggon, and buried near the Weser, on the spot where Corbie afterwards arose. Upon the death of Charlemagne, for some reason,—probably to prevent its falling into the hands of the idolaters,—it was transported beyond the Weser, and, the Saxons attempting to rescue their favourite, a battle took place, in which they were defeated. From this circumstance the spot received the name of Armensula. To prevent the recurrence of such attempts the pillar was thrown into the Inner, but only, as it turned out, to undergo a yet stranger vicissitude. When a church was built near Hillesheim, it was brought into it after much preliminary lustration, and set up in the choir, where it long was used to hold the lights upon the days of festival. We have dwelt more at length upon this idol, as there seems a certainty, or at least a strong probability of its worship having continued with the Saxons who possessed themselves of Britain. The ancient name of Irmin Street would appear to have been derived from Irmensal.

The Saxons had many other deities; indeed their number is so great that the detail of them would too severely task the patience of most readers; we shall therefore mention but two more —Ochus Bocus, and Neccus. The first of these, under the corrupted names of old Bogey and Bogle still lingers in nursery tales and among our northern peasantry. We also find it, if Verelius be right, in the legerdemain of the Italian conjurors— "ochus pocus!" but they probably borrowed it from our own Hocus Pocus. Bochus is no doubt derived from the genuine Teutonic Bock, a goat, for without any apparent reason the goathas often been made symbolical of evil, amongst Christians as well as Pagans. Thus we read in Matthew;

"And he shall set the sheep on his right hand, but the goats on the left. Then shall he say unto them on the left hand, depart from me ye cursed into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels."

"Hence we see why, in the Saturnalia of witches, the devil so often figures in the shape of a goat. Neccm, or the Neck, may with some confidence be received as the original of our Nick, though his dominion was over an opposite element. He dwelt in the waters, and whenever sudden cramp seized a swimmer, in consequence of which he sank, it was believed that Neck had got hold of him. Steel however, was potent against this busy fiend, as was also iron, and therefore those, who were going to trust themselves in the water, usually carried about a small piece of either as an amulet."

inspired authors and illustrators for over three centuries.

|

Gaspar Bellerus' Dutch Antiquities Nederlantsche Antiquiteyten (1613)  Sun

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aylett Sammes'

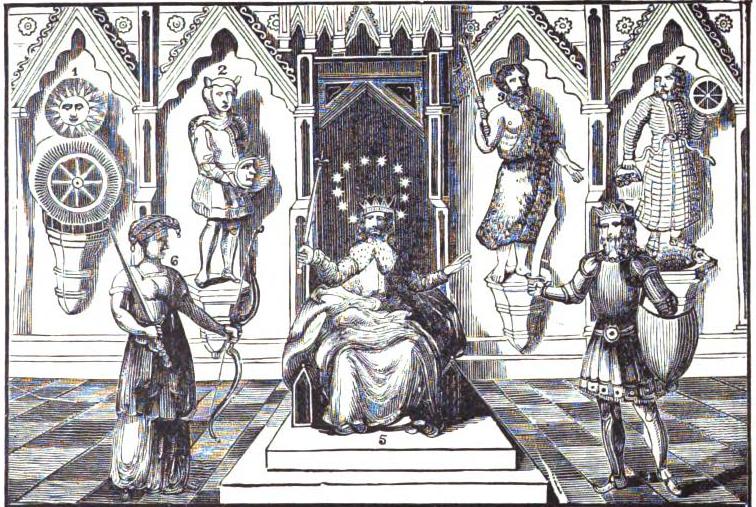

Britannia Antiqua Illustrata (1676) Featuring the first English translation of an Eddic poem: Hávamál  Woden Thor Friga  1689 Johann Jacob von Sandrart Druid performing a sacrifical ceremony to Sun and Moon Trogillus Arnkiel's Cimbrische Heyden-Religion (1691) The Cimbrish Heathen Religion

1697 Les Délices des Pais-Bas The book contains a fold out page depicting the god Ermenseul (Irminsul) and the seven Saxon gods who gave their names to the weekdays.

John Michael Rysbrack Stowe's Sylvan Temple (1720-1729)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Joseph Schimmelmann's

Die Isländische Edda (1777)

'An English Travelor' writing in The New Monthly Magazine (1817) speculates, "Crodo or Crotto, formed out of the ancient German word Chrotte, whence the modern Grotte, a grotto. Crodo was the spirit of the caverns, and principally worshipped in the north of Thuringia, in the Harz mountains, where caverns are very numerous. The first propagators of Christianity in Thuringia and Saxony were particularly hostile to this Crodo, causing him to be formally abjured as a devil, probably because the new converts from paganism secretly continued to pay adoration to him in those caverns. He was represented under the figure of an old man standing upon a fish, to denote his abode in deep places, holding a basket of flowers in his right band and a wheel in his left." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

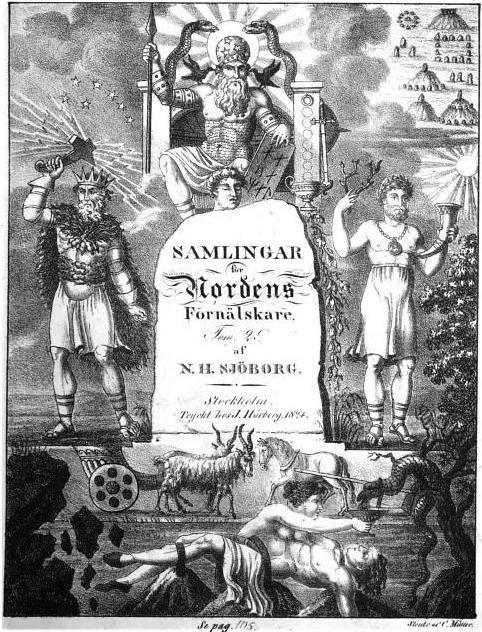

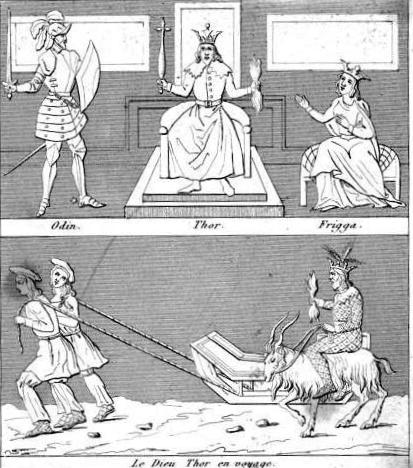

N. H. Sjöborg's Samlingar för Nordens Fornälskare (1822)

|

|

Thor appears with his lightning mallet Mjollnir for the first time. In addition we see

Thor's goat-drawn wagon (second step from bottom), Odin with Mimir's head,

and the plight of Loki and his wife Sigyn (foreground).

Notice the stars above Thor's head originating in the 1555 illustration by Olaus Magnus,

and the pointed royal crown first emphasized in the images used by Richard Verstegan.

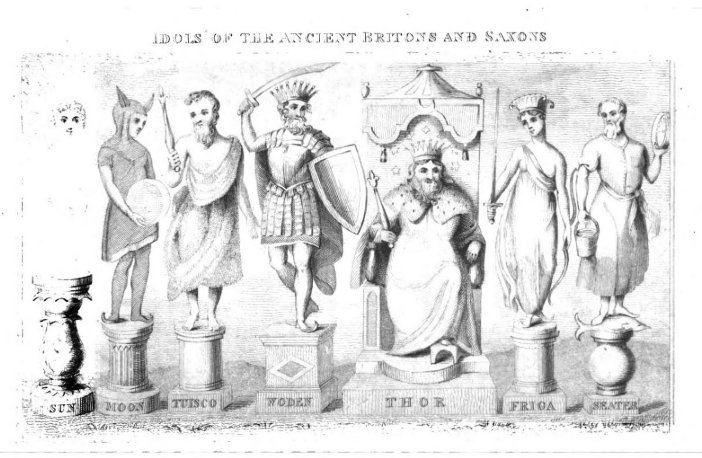

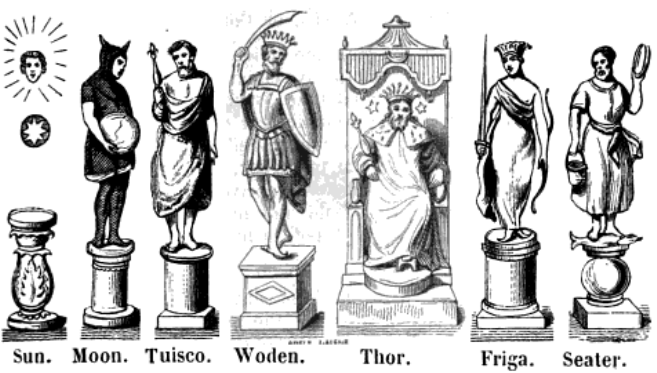

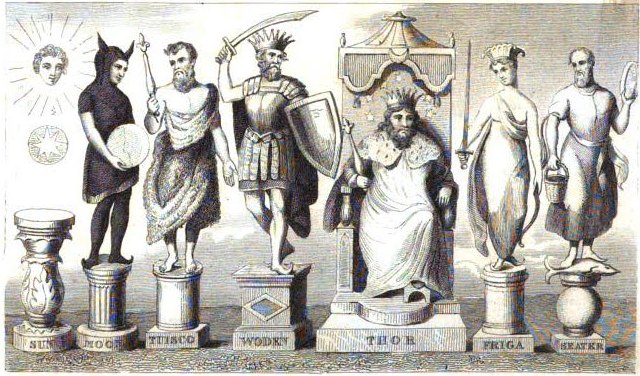

1823 William Pinnock's improved edition of

Dr. Oliver Goldsmith's Abridgment of the History of England

H.A.M. Berger's

Nordische Goetterlehre (1825)

Thor appears alone, and with his Hammer, known only from the Eddas.

In subsequent images based on the weekdays, he carries a staff instead.

Thor

|

Christian August Vulpius' Handwörterbuch der Mythologie (1826)

|

1834 Saturday Magazine (in series)

Reprinted in Ladies Garland (1838)

The Idols of the Saxons

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

| Woden | Thor | Friga |

Seater

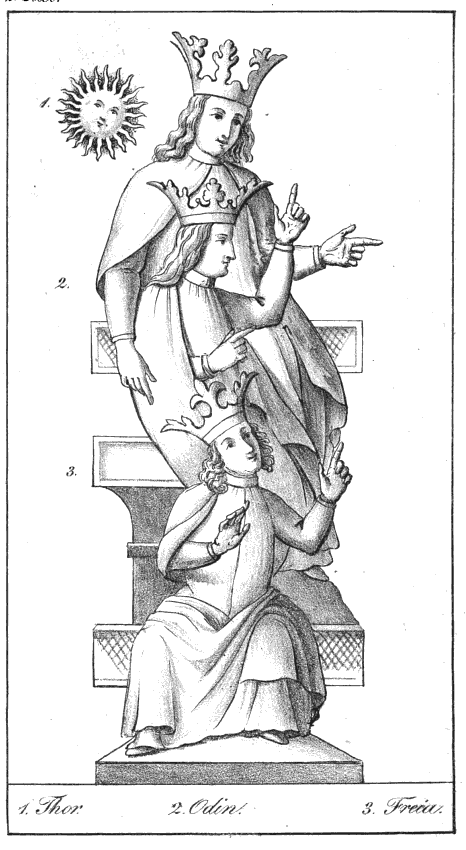

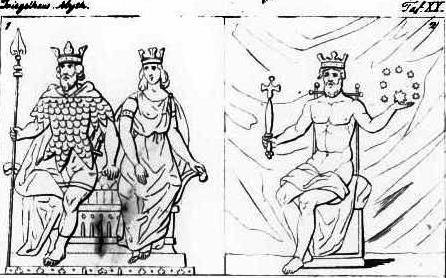

1837 Leopold Ziegelhauser's

Allgemeine Populäre Götterlehre

Sun, Moon (labeled as Ostara), Tuisco (left to right)

The captions read:

Odin and Friga on the World-throne Hlidskjalf,

Thor, Sarter [sic] with the Fish (left to right)

1839 Goldsmith's History of England

by Oliver Goldsmith

1840 William Pinnock & Oliver Goldsmith

An Abridged History of English Idols

This image and the one directly above are based on Pinnock's illustration from 1823.

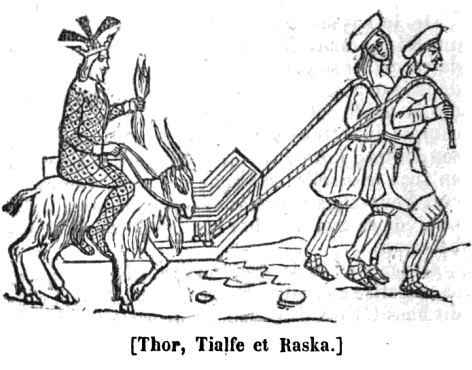

Jules Raymond Lamé-Fleury's

La Mythologie Racontée aux Enfants (1845)

|

|

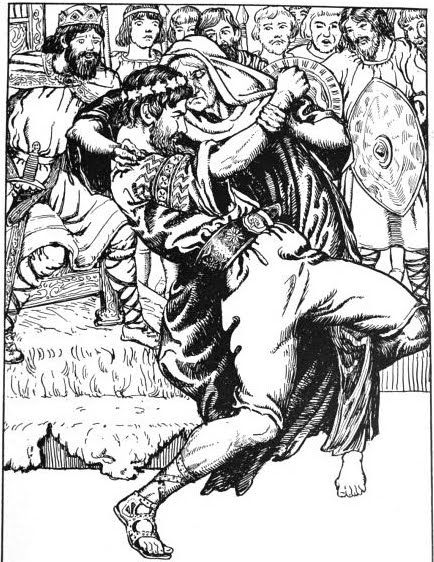

Odin, Frigga and Thor are drawn from the Days of the Week.

Thor, his goat(s), Thjafli and Roskva come out of Snorri's Edda.

1848 William Brodie Gurney

A Lecture to Children and Youth on the History

and Character of Heathen Idolatry

|

|

Laure de Lagrave Bernard's

Les Mythologies de Tous les Peuples

Racontées à la Jeunesse (1854)

1856 Dr. William Bell

On the English Nomenclature of the Days of the Week

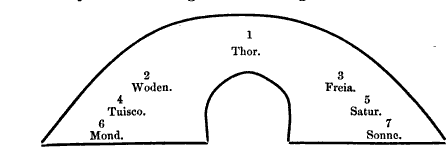

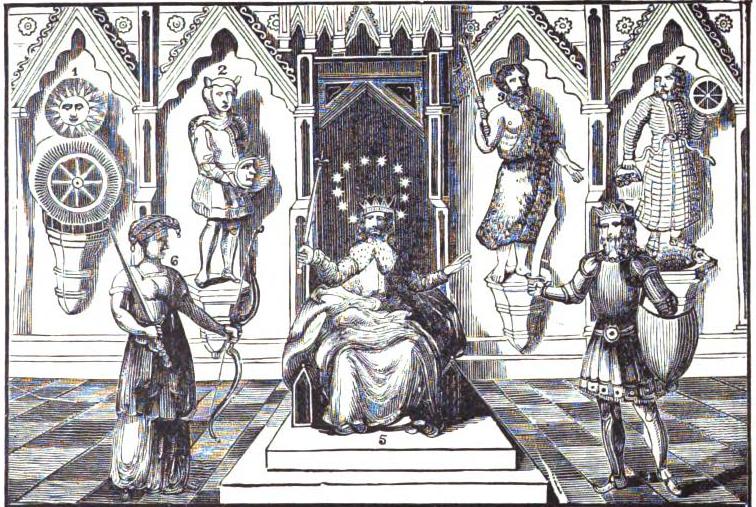

This is the order in which our seven deities of the week days rank as to power in the Scandinavian and Teutonic mythologies. It will be my purpose to shew you how this rank holds good in the sequence of these days, and how we must place them and commence, to retain their rotative precedence with the successive progress of each week. It is according also to this rank that we find the principal deities placed in the representations left to us of them. There is an old blazonment at the University of Upsala with Thor, Woden, and Friga thus relatively placed, and the succession of the rest seems natural and necessary. When we, therefore, picture the whole seven, seated in conclave, (like the Homeric gods on Olympus), in the halls of Muspelheim, the invisible heavens; or quaffing mead by the side of their heroic sons of earth, in the bright Valhalla, we must imagine their position according to the following scheme:— |

||

|

||

|

1864 Robert Bigsby Jr.'s Irminsula, or, the “Great Pillar” The image of Irminsula is probably derived from Trogillus Arnkiel's Cimbrische Heyden-Religion (1691) or a verbal description of the god. |

||

|

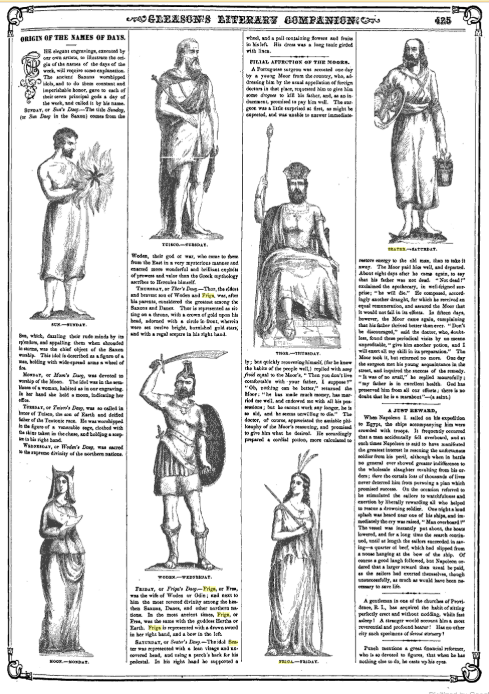

1868 Gleason's Literary Companion, Volume 7 Origins of the Names of Days  |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Sun |

Moon

Tuisco Moon

Tuisco |

Woden |

Seater |

Thor Friga

Frank Stockton Dobbins'

Gods of Our Saxon Ancestors (1883)

Sun, Moon, Tuisco, Seater (on wall)

Friga, Thor, Woden (foreground)

The image above appears to be based on this earlier image from an unknown source.

| Friedrich Gotthelf in Das Deutsche Altertum (1900) concludes, |

Even into the 20th century, Thor was sometimes depicted wearing a crown of stars.

Besides these illustrations, numerous prose accounts of the Seven Saxon Gods appeared in print until the early 1920s. Today, Verstegan's work still serves as inspiration for artists into the 21st century....

| ||||||

|

The work by Samuel Fallows & Henry W. Ruoff concerning the names of the days of the week published in Human Interest Library (1914) appears to be the first independent interpretation based in the Eddas. GOOD DAY! |

||||||

| [HOME][POPULAR RETELLINGS] | ||||||