The Mythology Feud

Adapted from an essay by Kira Kofoed at The Thorvaldsen's Museum Archives

Translated by David Possen

"In Norse mythology art will meet its grave," —Torkel Baden (1820)

[HOME]

[POPULAR RETELLINGS]

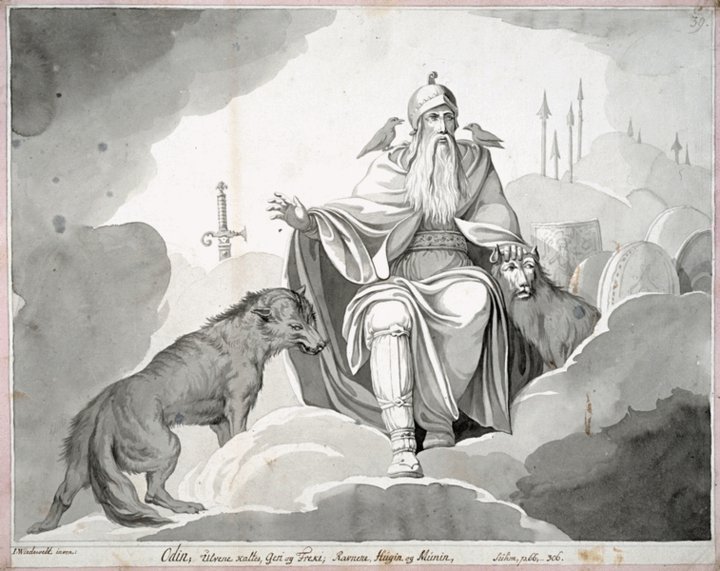

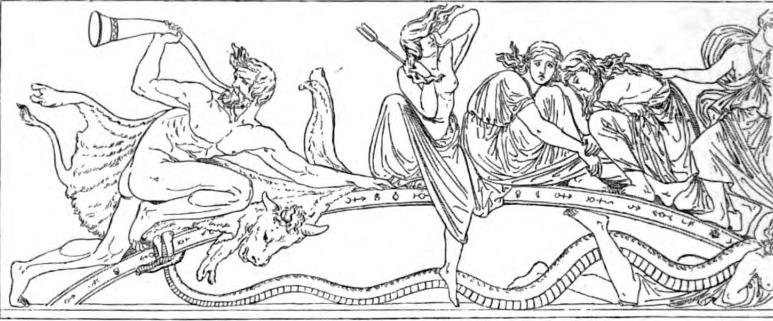

1821 A scene from the Van-As War from H.E. Freund's The Ragnarök Frieze

|

The Feud Over Norse Mythology |

|||||||||||

|

The Danish National Art Library houses a collection of pamphlets from the period between 1812 and 1821, gathered at the time under the title “Mythologie-Striden” [The Mythology Feud]. All of these were originally position papers in the scholarly journals of the day. As the collection’s title suggests, debate between the two sides was hardly placid: anonymous slander and personal attacks among the parties were a matter of course. Intriguingly, both sides sought trump cards in alleged statements by sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, which were cited in defense of both of the two main standpoints. The basic point of contention was the extent to which it is defensible to employ motifs from Norse mythology in contemporary sculpture, given that Christian and classical antique motifs have so long been available to draw on. In Lutheran Denmark, Christian motifs were regarded as paradigmatic. At the Academy of Fine Arts, the use of such motifs was established practice for students competing for the medals that granted access both to higher stages of the Academy’s program and to the final scholarships that would allow them to travel abroad after completing their studies. Meanwhile, classical mythology, particularly that of ancient Greece, was thought to be capable, despite its pagan religious content, to serve art’s purpose: to ennoble humanity by depicting and shaping the beautiful, the great, the true, the good, and the orderly. With the advent of Neoclassicism, and not least with the theories published by archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, both in his 1755 manifesto Gedanken über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst [Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture] and in his Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums [History of the Art of Antiquity], first published in 1764, ancient Greece came to be taken as an image of the ideal society with democracy, freedom, rational science, advanced philosophy, and the cultivation of the beautiful and the good as cardinal principles. Classical art was regarded as reflecting this ideal society in the purest possible way, and hence was worthy of emulation. By contrast, the Aesir and Jotun of the pagan North, in their animal hides, were worshipped by societies and peoples who (in the critics’ view) were far from the Greeks when it came to the visual arts, architecture, or social structure—to the extent that any such accomplishments by the Norse are recognized at all. In Denmark, interest in Norse sagas, legends, and prehistory had been on the ascent since the 1750s, alongside similar bursts of interest in the neighboring countries (in Sweden, for example, these led to the founding of the Geatish Society in 1811). In the wake of Denmark's alliance with France in the Napoleonic Wars and the state bankruptcy that followed, however, an acute demand suddenly emerged in Denmark for a unifying and edifying heroic image. It was in this context that the “Mythology Feud” first started to flare up in earnest. As the nation’s educational and advisory body on art, the Royal Academy of the Arts played a central role in this game; indeed, the main parties to the debate were primarily individuals with ties to the Royal Academy. "In Norse mythology art will meet its grave." This is the curt verdict offered by philologist Torkel Baden, secretary of the Academy of Fine Arts, in his monograph Om den nordiske Mythologies Ubrugbarhed for de skjønne Kunster [On the Unusability of Norse Mythology for the Fine Arts]. Baden’s monograph was, among other things, a response to a lecture by the theologian Jens Møller later published as Om den nordiske Mythologies Brugbarhed for de skjønne Tegnende Kunster [On the Usability of Norse Mythology for the Fine Drawing Arts], Copenhagen 1812. Møller went so far as to argue that Norse motifs could be used in membership pieces, but not in medal competitions. While there was a wide consensus that it was appropriate for poets to mine Norse myths freely for material, Baden found it unthinkable that sculptors could derive anything good from them: "Everything that Norse mythology contains is misshapen, useless for fantasy." Baden was convinced that the motifs found in Norse mythology would detract from art’s highest aims, which only Greek (and Christian) motifs could live up to: "Greek mythology moves them as citizens of the educated world. For in it are contained the principal fundamentals of all the branches of knowledge that dignify humanity and distinguish it from the great horde, namely, the fundamentals of astronomy, geography, chronology, and other sciences that enlighten and sharpen the understanding; and it is the language of fantasy, which all cultivated people understand, and the knowledge of which is first eradicated with the culture." As Baden saw the matter, Norse mythology was reconstructed from a slovenly muddle of sources, many of which, moreover, were of murky Greek origin. The resulting corpus is messy and disorderly; only rarely is it clear how an artist might depict these mythic beings so that they could be recognized easily, making the stories at issue accessible to the beholder. On the side of classical mythology, Karl Philipp Moritz’s Götterlehre oder Mythologische Dichtungen der Alten, Berlin 1791, which is also found in Thorvaldsen’s book collection, illustrates how a cycle of myths was described and activated as a manual, or medieval pattern-book, for artists to consult when seeking to depict a motif correctly according to its sources and precedents. To this can be added the innumerable actual artworks preserved from classical antiquity, which could be studied as casts even in Copenhagen. The Danish painter C. F. Høyer, a friend of Thorvaldsen, had views similar to Baden’s. From his position as member of the Academy of Fine Arts’ plenary committee, Høyer argued in a series of opinion pieces that in the name of enlightenment and edification, artists should depict Christian or classical motifs rather than those of Norse mythology, which would give rise only to idolatry and barbarism. On June 23rd, 1821 Høyer sent Thorvaldsen a short pamphlet published earlier the same year as a summary of the painter’s thoughts. Both Baden and Høyer ultimately fell foul of the Academy, not least because of this dispute. In 1826, Høyer was excluded from the plenary committee; and Baden, citing irreconcilable differences, resigned from his position as secretary and librarian in 1823. The art historian N. L. Høyen also took a critical line against the use of motifs from Norse mythology. On June 28th, 1821, Høyen addressed the student association in defense of his postulate that Norse mythology was of no benefit to art.

The president of the Academy of Fine Arts, Denmark’s Crown Prince Christian Frederick (later King Christian VIII of Denmark, 1839-1848), also took part in the dispute, here on the side of Norse mythology. In 1819, the philologist and archaeologist Finnur Magnússon, himself an eager contributor to the public debate, was hired by royal command as an instructor in Norse mythology and literature at the Academy of Fine Arts. Since 1814, the Academy’s professor of history had already been bound by royal decree to include topics drawn from Norse mythology in the curriculum. This was intended to provide students with the requisite basic knowledge of the literature, legends, and figures of the past, along with archaeological discoveries to date. Furthermore, efforts were made to have Johannes Wiedewelt’s 1780s illustrations to Johannes Ewald’s tragedy Balders Død [The Death of Balder] (1770, printed in 1775) engraved in copper, so as to widen familiarity with the gods and heroes of the North.

|

|||||||||||

| Thorvaldsen is Drawn into the Feud |

|||||||||||

|

At the height of the dispute, both Finnur Magnússon

and Torkel Baden appealed to alleged statements by Thorvaldsen

as trump cards for their positions. Magnússon reported a

conversation that he had had with the great sculptor on the

subject—unprovoked, as he emphasized:

"Objections have been made to unsightly elements in Freya’s team of beasts [i.e., the cats to which her car was harnessed], and at first glance these do not seem groundless; but one of the greatest artists of our land and age, namely, Thorvaldsen, declared to me orally, and without any prompting from my side, that he did find that objection groundless. A soulful artist would know how to portray Freya’s cats with beautiful tiger-like forms, and moreover with a character of a sort that could interest a thinking onlooker."

In an attempt to refute this claim, Baden stated that it was only out of politeness that Thorvaldsen had suggested transforming Freya’s cats into tigers, and that Thorvaldsen would not have been Thorvaldsen had he meddled with such trifles. On December 16th, 1820, in the same journal, Magnússon repeated that Thorvaldsen had incontrovertibly acknowledged—as had C. W. Eckersberg, another great artist of the day—that it was of value for “young artists-in-training” to acquaint themselves with Norse mythology. Baden’s trump card next came in the journal Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn, whose title page bore the headline Thorwaldsens dom over den nordiske Mythologie [Thorvaldsen’s verdict about Norse Mythology]. Here Baden cited Thorvaldsen as having declared that he would never concern himself with the Norse gods: When Thorvaldsen saw Nicolai Abildgaard’s sketch, which portrays the man licked forth from the stone by the cow, he said, “How exquisite is that man’s form! But it deserved a better pedigree. O cold North! who lets the animals’ master [humanity] be fed by animals, who lets the man who raises himself toward the heavens be fed by the stooping cow, the wisest creation by idiocy itself. And should the South deny me shelter, nay it is for Thee I long—it is to the East that I journey. Here Moses introduces God as saying: Let us make a man after Our image, after Our likeness. It is in this way that the sculptor sets to work when he seeks to produce something that corresponds to the ideal that floats before his eyes. God is his own ideal. In Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam we admire, if not the highest culmination, which no mortal can achieve, but the strength of the thoughts and their towering flight."

For his part, Magnússon publicly cast doubt on this claim. That led Baden to reveal his source: it was the floral painter C. D. Fritzsch, Thorvaldsen’s friend from his student days at the Academy, to whom the sculptor had said these words. Baden then repeated once more that Thorvaldsen would not have been the great artist he was if he had been capable of judging otherwise. It was these exchanges, in all likelihood, that prompted the Crown Prince to ask Thorvaldsen for a clear statement of support for the usability of Norse mythology in art (and thus for the fatherland) one year later. During that same year, a competition was announced with the aim of advancing the cause of Norse mythology; and this became the occasion for the Crown Prince’s blunt request to Thorvaldsen to send drawings with motifs from Norse mythology to himself or to the Academy of Arts. The evident purpose of this request was to demonstrate, once and for all, that if even the great Thorvaldsen could see nothing wrong with artistic portraits of the Norse gods and heroes, then all other criticism ought also die down: "I am well aware that there can be no question of you drawing [a submission] for the prize yourself. But it would be crucial for the matter at hand, as well as for the purpose of defending the value of Norse mythology, which has been denigrated so impudently (even though it always can, and should, be of interest, indeed of value, to Nordic artists), if you, assuming you have the willingness and the capacity, would sketch some drawings and send them to me or to the Academy. This would, in addition, silence the persons who, with unmatched shamelessness and mendacity, have put words in your mouth that you have never thought to utter, and which do not resemble your [actual] utterances either.—My aim is simply to allow truth to appear for a day, and to keep evil and partisan bias from attaching themselves to a field where Nordic artists perhaps successfully, and fittingly, could win honor and acclaim. At issue, in short, were the honor of the fatherland and the future of art in Denmark." No reply by Thorvaldsen to this forthright exhortation is extant; nor do we have any evidence of drawings being completed or sent. However, a later draft of a letter to Christian VIII does evince a positive attitude toward the artistic use of Norse mythology, albeit in a case other than that of Thorvaldsen himself: "His [namely, the sculptor and Thorvaldsen student Hermann Ernst Freund’s] sketches of representations of Norse mythology [are] highly interesting, and I expect of them something exquisite, for the splendor of our Fatherland and for the increase of its artistic holdings."

This draft letter, however, was not written by Thorvaldsen himself, but by his friend P. O. Brøndsted. In the final version of the letter, which Thorvaldsen did write himself, the topic goes unmentioned. This suggests that Thorvaldsen had consciously avoided putting any such clear declarations of sympathy into writing. In a different case, in which Thorvaldsen does discuss art grounded in Norse mythology (in a recommendation for the painter Andreas Ludvig Koop, who also worked with Norse mythological motifs), Thorvaldsen expresses praise exclusively for the technical element in the work at hand, passing over its content. In 1822, the residents of Copenhagener could read the following words of encouragement in the magazine Aftenblad: "Thorvaldsen also has in mind to model something from the Norse legendarium, which he will then execute in marble himself. This despite the efforts of some to make us believe that Thorvaldsen has roughly the same attitude toward Norse mythology as does the Secretary of the Academy of Fine Arts in Charlottenborg!!" That Thorvaldsen did not in fact do this was explained away entirely by appeal to his many active projects. And so it was that the uncertainty surrounding Thorvaldsen’s position persisted despite these statements. |

|||||||||||

|

Other Prominent Exhortations

|

|||||||||||

|

Adam Oehlenschläger and N. F. S. Grundtvig were among the poets and authors who paid literary tribute to the newly discovered epic treasures of Norse mythology. Both Oehlenschläger and Grundtvig urged Thorvaldsen to produce works of art with motifs drawn from Norse mythology. Oehlenschläger did so in the festive address to Thorvaldsen that he delivered during a sumptuous celebration in the sculptor’s honor held at Copenhagen’s Skydebanen [the Royal Shooting Range of the Royal Shooting Society] on October 16th, 1819:

Grundtvig, for his part, entreated Thorvaldsen at the dedication of the studio built for the sculptor in the garden of Nysø manor. The studio was dedicated on July 24th, 1839, and Grundtvig dubbed it “Völund’s Workshop.” In an excerpt from the poem cited in an article by Grundtvig, the studio is called a “cottage,” and Thorvaldsen is identified with Völund the smith:

Grundtvig prefaced his recital of this poem by issuing a somewhat sarcastic apology for speaking of the Norse legendarium in the first place: Though I have been asked to recite the song as well, I do not have the courage to do so without a little preface, which could defend or even apologize to people for my reference to the myths of the North, which still sound Chinese to most ears, though all the Latin ghosts, with Bacchus and Venus, are either greeted as household gods or known as garden sprites. Put briefly, the challenge for Norse mythology was not simply that it was pagan and, unlike classical mythology, had not been elegized by Winckelmann or Goethe, let alone used as a prototype, to a greater or lesser degree, ever since the Renaissance. The difficulty is also that, as a cultural sphere, Norse mythology was newly discovered and relatively unknown to archaeology and other scholarly fields. Crucial to the formal-visual language of Neoclassicism was the possibility of verifying the correctness of depictions of various historical periods, and in borrowings from the statues, coins, reliefs, etc., of classical antiquity. The story of Thorvaldsen’s mentor, the archaeologist Georg Zoëga, correcting some of Thorvaldsen’s earlier works in Rome because they deviated from their ancient prototypes, and the tale of the renowned 1803 model of Jason with the Golden Fleece, which the sculptor himself held were copied all too faithfully from ancient templates, are both anecdotes that, true or not, indicate in part the age’s demand for exactness and loyalty with respect to classical sources, and in part the artist’s own need for creative freedom in relation to a known original. The pressure on Thorvaldsen lasted years, and only increased with time. Thorvaldsen’s assistant, the sculptor Hermann Ernst Freund, attempted to persuade him, at the behest of Jonas Collin and others, to produce works drawn from Norse motifs: "At the outset he stated that he would produce a Thor; but later he always excused himself on account of his many tasks", Freund wrote to Collin in 1822. As early as 1804, Thorvaldsen’s former patron Herman Schubart had suggested that Thorvaldsen use Norse motifs for the statues in the new Christiansborg Palace, for which the architect C. F. Hansen was responsible: "Perhaps you would like to acquaint yourself with our old and interesting Scandinavian mythology. If so, then do write to our friend Stub, and ask him to send you by courier the part of Mallet’s Danske Historie [Danish History] that contains the Edda, a veritable masterwork. This book is found in my collection, and I will write to good Stub to send you whatever you need. Still, this idea about our Scandinavian mythology is only an undigested thought, which you by no means must accept, if you think better of it. Just consider that this could come to be a work that can make your talent immortal." |

|||||||||||

| Thorvaldsen’s Position | |||||||||||

|

Unfortunately, we have no extant reply to Schubart by Thorvaldsen. But Schubart’s next letter indicates the outcome clearly—Thorvaldsen wished to work on the basis of classical myths known to all: "Your thought about the immortals whom you will render eternal at the gate of Christiansborg Palace is supremely fitting. It is better than if you had taken something from Scandinavian mythology, which is only poorly known; whereas everyone knows and loves Minerva, Jupiter, Nemesis, and Hercules. In Rome, moreover, one can hardly work on anything other than Roman and Greek gods and heroes."

What is more, the vocabulary of

classical antiquity is one that Thorvaldsen had learned to

master completely—by virtue of his early education, his later

studies, the help of Georg Zoëga, and his own and others’

collections of objects from antiquity—as well as to scramble it

in order to generate new meanings. In short, Thorvaldsen had

little incentive to incorporate the Norse legendarium into his

work. |

|||||||||||

|

That would be left to a younger generation

of artists. See especially Thorvaldsen's assistant

Herman Ernst Freund

(1786-1840), sculptor of the Ragnarök Frieze. Nevertheless, there are four extant drafts of Thorvaldsen’s own coat of arms, all of which depict a standing or sitting figure that has been identified—on the basis of, among other things, the memoirs of Thorvaldsen’s valet C. F. Wilckens—as Thor. These drafts bear clear reference not only to Norse mythology, but also to Thorvaldsen’s last name, his Nordic roots, and his Icelandic ancestors on his father’s side. |

|||||||||||

Thorvaldsen's finished sketch for his own Coat of Arms with standing Thor motiff [Bibliography] |

|||||||||||

[POPULAR RETELLINGS]