THE TEMPLE AT OLD LEJRE

Zealand, Denmark

The Heroic Legends of Denmark

by Axel Olrik

CHAPTER VI

THE ROYAL RESIDENCE AT LEIRE

1. THE ROYAL RESIDENCE OF THE HEROIC LAYS AND THE TESTIMONY OF THE MONUMENTS.

To determine the location of the royal residence of Leire (Old Norse Hleiftrar; Middle Danish Lethrce; Modern Danish Leire), linked in the old lore with so many brilliant rulers, is one of the most difficult problems for historical investigation. In trying to solve it, it will be of importance to note how far back in time the mutually contradictory witnesses go. The heroic lays are agreed on letting every one of the Danish kings of the Scylding race have his residence in Leire. In the Quern Song [Gröttosangr] there is mention of the Hleitirarstóll (the residence or throne at Leire), i.e., the dominion of Denmark, as far back as the peace of Frothi. According to the Biarkamal, Hrolf is attacked in the Leire castle. According to the lay of Ingiald in Saxo, the young avenger of his father is called worthy to be the king of Leire and the ruler of Denmark. In the Bravalla Lay, the warriors from Leire are the housecarls of Harold Wartooth. In agreement with this, a skald of the eleventh century designates King Svein Estrithsson as atseti Hleiftrar, i.e., he who has his residence at Leire.

The same is stated with still more detail in the medieval accounts. In the little chronicle from the Roskilde district we are told that the first king, Dan, founded Leire even before the uniting of the realm; that Ro later adorned it most beautifully, and that the sepulchral mounds of Dan, Ro, and Halfdan are to be found there (SRD i, 223-225). Saxo, on the other hand, asserts that Hrolf kraki built the town of Leire and adorned it most beautifully so that as the royal residence it far outshone all the other capitals of the country. However, he mentions in an earlier passage, that Hrolf as a little child had been sheltered in Leire castle from an attack of the enemies. Still further we are told how the Jutish petty King Amleth sought to avoid the overlordship of the "Leire King,"; also that Harold Wartooth united all parts of the realm anew and fixed his residence at Leire where he had also his sepulchral mound thrown up. In fact, Saxo knows still another king, Olaf (ninth century), who has given his name to a mound near Leire.* The Icelandic tradition is in accordance with Saxo: the progenitor of the race, Skiold, founded the royal castle in Leire, on the island of Zealand, and "there was the residence also of most of the succeeding kings "; even the sons of Lothbrok still dwell at Leire.

No other royal residence can in the least compare with Leire, according to the witness of heroic lays. Jaelling is mentioned once by Saxo in connection with Offa and Vermund, and Jselling Heath (Jalangrs heiHr) in the Icelandic story of the Peace of Frothi. In the lays, it occurs not at all. In a single Icelandic passage Ringsted (Hringstaftir) is mentioned as the seat of Frothi the Famous (hinn fragi). Sigersted (Sigarsstaftir) is properly the residence of the race of Sigar.* But what is that against the long line of kings in Leire, away back to the remotest antiquity, with the many events from the time of the Peace of Frothi until Hrolf's fall, with its royal sepulchres and all the splendor of the "Leire kings" and the "Leire throne," these strong expressions of the unity and power of the Danish people? The very oldest written account agrees entirely with the passages cited. The German historian Thietmar of Merseburg, writing in the beginning of the eleventh century, relates as follows about the heathen practices of the Danes:

"There is a place in those regions which is the capital of the realm, called Lederun, in that part of the country which is called Selon where, every ninth year, in the month of January, somewhat later than our Christian Yuletide, they assemble together and sacrifice to their gods 99 men and as many horses, dogs, and cocks or (?) hawks, believing that these will be of service to them in the realm of the dead and atone for their misdeeds." There can be no doubt that Selon here represents Zealand (Old Norse Selund) and that Lederun stands for Leire (Old Norse at Hleiftrum, Old Danish at *Ledhrum)."

In other words, all investigations undertaken on the spot lead us to reject in every respect the conception of the situation of Leire which is found in the written documents.

Which of the two kinds of sources are we to believe? The testimony of old songs and legends is of course not the very best argument when a definite historictopographic problem is to be settled. But how about Thietmar's statement concerning the great sacrifices which were offered up at Leire? Is it permissible to rely on him, and to declare the arguments of the archaeologists to be without force?

Thietmar has the air of being well informed, but we shall have to call a good deal of his description in question. First of all, it is incorrect for him to mention these sacrifices as taking place in his own time, for they had not been made for some fifty or sixty years before his day, and were therefore known only by hearsay. In the second place, we can see, by comparing his data with Adam of Bremen's description of Upsala, that the details are about right, to be sure, but that the numbers seem greatly exaggerated. Considering that the entire Swedish people sacrificed nine men in their great offerings, it sounds incredible that the Danes should under the same conditions have sacrificed ninety-nine. Very possibly the entire number of sacrificial animals reached that size. Most important of all, however, is the circumstance that the localization of the sacrifice in Leire is by no means as certain as has been thought. During recent years, Thietmar's own manuscript of the Chronicon has been examined, and it has been possible to understand the entire history of its origin. He began writing it in 1012, when he probably wrote the greater part of Book I, including the passage where the heathen practices of the Danes are mentioned; he then continued, until the whole work was ready, in 1018. In 1016 he completed the first book, after having obtained several new sources and made marginal glosses on what he had written before. The passage about the Danish sacrifices did not originally contain the name of Leire. It read only: "There is a place in that region, the capital of the realm, where they assemble every ninth year, in the month of January, later than our Christian Yuletide, and sacrifice to their gods," etc. When going over his work, later, he made a little addition to the word "capital," adding the words " called Leire, in the district of Zealand." In the course of the years intervening he had received information concerning Denmark and the battles of Canute the Great. It is very likely that he learned only then that Leire was the name of the royal Danish residence.

Considering all this, Thietmar's chronicle cannot claim the authority of contemporary testimony grounded on first-hand observation. His information is made up of legendary traditions worked together by a man who was not gifted with any special insight into the matter. In other words, his testimony is of the same kind as all the other traditions or songs about the renown inseparably connected with the name of Leire during the Viking Age. And it is the rule that tradition and monuments offer contradictory evidence in this respect.

The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg

Chapter 17:

"Because I have heard strange stories about their ancient sacrifices, I will not allow the practice to go unmentioned. In those parts the center of the kingdom is called Lederun (Lejre), in the region of Selon (Sjælland), all the people gathered every nine years in January, that is after we have celebrated the birth of the Lord [Jan 6th], and there they offered to the gods ninety-nine men and just as many horses, along with dogs and cocks— the later being used in place of hawks."

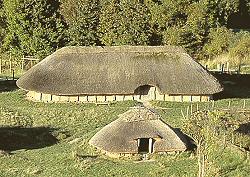

Two Great Halls at Lejre

2 cm tall figurine found at the site

interpreted as Odin on Hildskjalf

2007 J. D. Niles (ed.)

Beowulf and Lejre

On the basis of legendary analogues, specialists in the Old English poem Beowulf have long inferred that the action of the main part of that poem is situated at the village of Gammel Lejre on the island of Zealand, Denmark. Archaeological excavations undertaken from 1986 to 1988 under the direction of Tom Christensen of Roskilde Museum yielded spectacular confirmation of that inference by uncovering the remains of two great halls at Lejre dating from ca. AD 680 to 990, one built on the site of the other. At that time, this discovery had little impact upon Beowulf scholarship, in part because the chief monograph reporting on the excavations was available only in Danish. In 2004–05, however, a new round of excavations revealed that a still earlier hall had once stood elsewhere at Lejre. This hall has been dated to the mid-sixth century, very close to the time when the action of Beowulf is set. The question of the Danish origins of the Beowulf story is thus now highlighted. The main purpose of this book is to bring these archaeological discoveries to the attention of a wider public, with analysis of their significance. The book consists of five parts:

1. A translation into English of Tom Christensen's 1991 monograph Lejre—Syn og Sagn (Lejre—Fact and Fable) together with a new chapter by Christensen on the most recent excavations.

2. A presentation of other important archaeological studies relating to Lejre, including reports on the Iron Age cremation mound named Grydehøj, which dates from ca. 630 to 660.

3. Essays by John D. Niles and Marijane Osborn evaluating the significance of these finds from the perspective of Old English scholarship, with attention to the complex legendary history of Lejre.

4. A presentation, in their original texts and in modern English translation, of the chief medieval Latin and Old Norse documents that mention Lejre as the seat of power of the early kings of Denmark.

5. Some impressions of Lejre made by antiquarians, travellers, poets, and artists who have known that place during the modern period and have described or evoked it in various ways.

Detail from the Oseberg Tapestry,

showing hanged bodies in a tree.

Found in a Danish peat bog in 1950 where he had been placed more than 2,000 years ago, 'Tollund Man' died approximately 400 BC. The acid in the peat, along with the lack of oxygen preserved the soft tissues of his body. Scientific analysis has shown that Tollund Man died by hanging rather than strangulation. The rope left visible furrows in his neck, and although the cervical vertebrae were undamaged, as they often are in hanging victims, radiography showed that the tongue was distended—an indication of death by hanging.

Also Visit

Germanic Mythology