|

. |

| |

|

|

Eduard Ille (June 17

1823—Decemeber 17, 1900) was a painter, illustrator and

poet, who lived in Munich all his life. After graduating from high school, he

studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich under

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and Moritz von Schwind.

After trying unsuccessfully to work in the field of

religious painting, he turned to illustration in the

1850s. During this time, he provided drawings for

woodcuts for L. Bechstein's Deutsches Sagenbuch 1853, M.

Schleich's Punsch and J. J. Weber's "Illustrirte

Zeitung". Through his work on "Hauschronik", he

was gradually drawn into full-time employment at the Munich magazines

Münchener

Bilderbogen and

Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves), the latter of

which he became co-editor in 1863 and played a large

part its extraordinary success with his fresh and

imaginative stylized caricatures. In addition, Ille also

produced an independent series of woodcuts: The seven

deadly sins, a series of 8 drawings cut in wood, 1861;

Lamport's living picture book with moving figures, 1863;

Little Red Riding Hood, composed in 6 pictures, 1872;

Grimm's Kinder- und Hausmärchen in pictures, as

well as illustrations for other works. In 1868 the Munich Academy honored

him with the title professor.

|

|

| Eduard

Ille |

King

Ludwig II |

During his life, Ille executed several

important works of art commissioned by the Bavarian King

Ludwig II. His murals at Schloß Berg include Lohengrin

1865, Tannhäuser 1865, Niflunga Saga 1867, and Parsifal

1869. An oil painting titled Die Meistersinger von

Nürnberg (1866) also formerly hung there. Ille also

executed murals in the King's dressing room at the

Neuschwanstein Castle from the life of Walter von die

Vogelweide and Hans Sachs. He also wrote some dramas and

opera texts, as well as numerous occasional poems and

verses for the "Flying Leaves" and for series he drew.

His extensive art collection and a valuable collection

of his own drawings were auctioned off in 1901 at

Mössel, Berlin.

|

|

Translated from portions of Gunter

E. Grimm's "Niflunga-Saga.

Zu einem Gemälde von Eduard Ille"

(2015), Paul Hermanowski's

Die Deutsche Götterlehre und ihre Verwertung in Kunst

und Dichtung (1891),

pp. 193ff,

Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der

Antike bis der Gegenwart (1925) and a

contemporary newspaper account (Dec 25, 1867) |

|

|

|

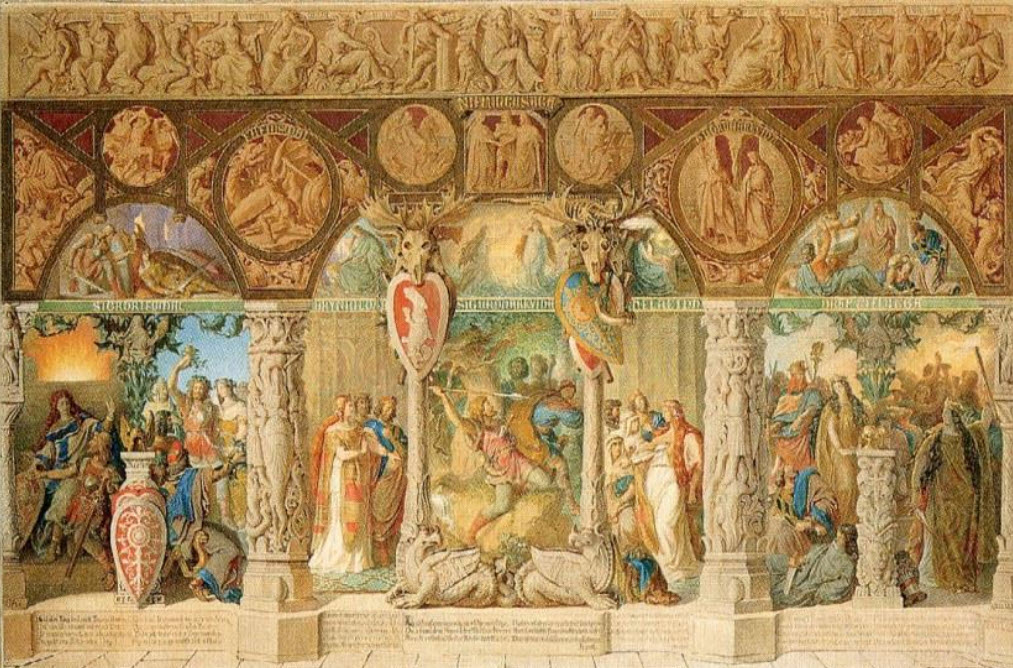

The Tempera Painting "Niflunga-Saga" by Eduard

Ille, 1867. |

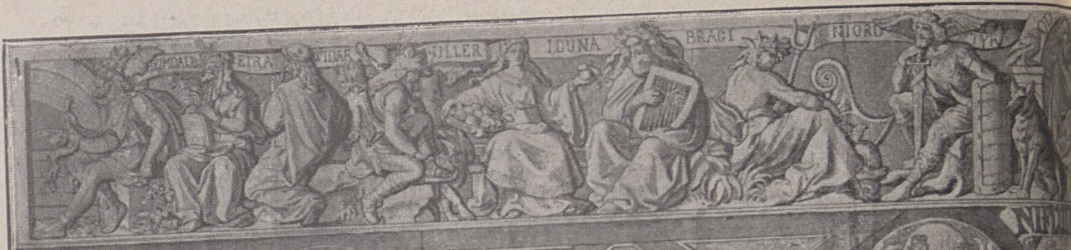

A relief-like frieze of an assembly of the Old

Norse gods is found over the entire large sheet of

21 images in total.

(Heimdall, Eir, Vidar, Uller, Iduna, Bragi, Njord, and

Tyr are seated to the left of Odin, enthroned at the

center; while Frigga, Thor, Freyr, Freyja, Baldur,

Forseti and Vali are seated to the right of Odin.

|

|

|

Detail of the Frieze of Old Norse

Gods, left (above) and right (below) of Odin. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eduard Ille's Niflunga-Saga as described

by Paul Hermanowski (1891):

|

"For the painter who desires to depict the

"Niflungen saga"

as Eduard Ille does for King Ludwig in watercolor, it

is not inappropriate to

first present the Aesir and Aesir. Up

in the top middle, we find Odin seated on his

throne, grasping his spear

upright in both hands. A thick, wispy beard

frames his face. One does not notice that he is

missing an eye. A helmet-like cap covers his head. A

long cloak envelops his figure. On either side are

the wolves at his feet and the ravens on the

armrests of the seat.

There now follow to his right, Frigg with a distaff

and spindle in her hands, and to his left, Thor,

dressed in battle garb, gripping in his iron-clad

fists the mighty club-like hammer, the handle of

which is long rather than short. A helmet adorns his

head. He also buckled on the power belt. Behind him

are his two long-horned bucks in front of the

two-wheeled chariot.

Now come Freyr and Freyja. Both are wreathed and

dressed in long robes. Freyr has a sheaf of corn in

his right hand and a bowl of fruit in his left. A

sickle hangs from his belt. Freyja has a torch in

her right hand. A precious jewel adorns her neck and

breast, and a cat sits on her

left side.

This is followed by Baldur, the judge's staff in his

right hand, his head surrounded by a halo, also in a

long cloak-like robe. Beside him sits Forseti, his

son, raising the index finger of his right hand and

holding in his left arm a magistrate and a tablet of

the law.

The last picture on the right shows Vali armed as a

warrior. His left hand rests on a powerful round

shield, with his right he holds a bow. On the ground

lies a quiver with arrows.

As on the right, deities are all seated on Odin's

left. There we first see the battle god Tyr. A helm

tipped with mighty eagle wings covers its head. He

rests his chin on the hilt of the mighty sword,

which he grips in his right hand. On the edge of his

large rectangular shield he has placed the stump of

his left arm.

To the left, in front of him sits Njördr, with a

trident, the reed-crowned hair and the dolphin under

his right foot marks him as a sea god. His torso is bare.

Then Bragi and Idun follow. A wreath adorns Bragi's

rich, curly hair. His beard is full. A wide cloak

envelops him. With both hands he grips the strings

of the harp, which is on his knees.

Next to this old man sits the youthful Idun, handing

him an apple with her left hand, while holding the

bowl filled with apples with her right.

Uller now follows, dressed in a fur coat and hat. He

has his bow over his left shoulder and the quiver

with arrows on it hangs on his back. He has already

strapped his ice skate under his right foot, he is

just about to stop the left foot from getting one

too. A hound looks up at its master for prey.

Then comes the silent but strong Vidar. He put his

finger to his mouth as a sign of silence.

After him we see Eir, the goddess of Ieechcraft. She

holds a healing herb in her right arm.

Health-bringing plants are also at their feet. There

is a bowl on the left knee. With both hands she

holds a rune tablet in the right one.

Heimdall forms the end of the left-hand side or the

beginning of the entire upper frieze. From its perch

on a bridge-like ledge, the rainbow arches. A

ruffled robe covers his torso. Listening sharply, he

peers out into the distance. He has his sickle-like

horn in front of him on his right knee. He seems to

want to put it near his mouth; for the giants may

already be approaching."

|

|

The individual songs of the Edda are

implemented scenically on the middle level of the picture. In the

center is the title of the painting "Niflunga Saga",

then in two medallions, the two Eddic songs "Fafnismal"

and "Gudrunarkvida." The pictorial scenes are garnished

with all kinds of elements of the Bavarian

Berghütten-romantic style with its Alpine charm.

Above, two bare elk skulls, garnished with a sword-axe

and morning star, grin down. Below, two griffin-headed

dragons support scultured pillars on which two fantasy

coats of arms are hung.

The reverence that Ille shows his king here is unmistakable: Ludwig II was

the owner of eleven hunting lodges and Berghütten

(mountian-lodges). Louis' declared model was the

French "Sun King" Louis XIV. Hence the choice of the

Norman shield type —round at the top and tapering

at the bottom — and three golden lilies on a blue

background, the floral emblem of the House of Bourbon.

The rose in the middle of the shield could be

reminiscent of the "Geldern rose", a medlar flower. The

Geldern coat of arms is based on the 878 AD legend of

Wichard and Lupold von Pont's fight with a dragon. The

second coat of arms, with its red base color, could be

reminiscent of the coat of arms of the English king

Richard III. But since any legendary or historical

connection is lacking, it is more likely a fantasy coat

of arms.

The names of Eddic songs appear in gold letters on a

green background. The names "Sigrdrifumal",

"Brynhildar", "Helreidh" (Brunhilde's Hel-Ride), and

"Drap Niflunga" (Murder of the Niflunge) refer to the

images in the semi-circular arches, in addition the

names of the characters depicted in the scenes are

written in the manner of a schoolmaster. In the center

is the scene with the murder of Sigurd. As is well

known, Hagen killed Siegfried, who was kneeling at the

spring, by throwing a spear from behind.

|

|

|

|

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE |

|

Eduard Ille is best known for a series of paintings

based on medieval legends. He first came

into contact with the Nibelungen legend as a student

of Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, who became

famous for his Nibelung frescoes in

the Munich Residence (the former royal palace of the

Wittelsbach monarchs of Baveria), which he painted between 1827

and 1867. During this time, Schnorr was a professor

at the Munich Art Academy. In 1846 he left Munich

and went to the Dresden Art Academy.

Ille's own interest in the Nibelung legend came

about 20 years ago later, in 1865, when his

unfinished painting "The Song of the noble knight

Tannhäuser" aroused the interest of the Bavarian King

Ludwig II, a lover of art. The king liked the work

so much that he instructed Ille to complete the picture

immediately, and commissioned pictures of Lohengrin and

Hans Sachs. The pictures still hang in the living room

and study of Berg Castle on Lake Starnberg, which is

privately owned by the Wittelsbach family. Ille's estate

is located in the Munich literary archive Monacensia and

consists of sketches, seals and 55 volumes of diaries

and appointment calendars, that Ille composed between

1842 and his death in 1900, containing meticulous

accounts of his daily life. This diary is a primary source for information about Ille's day-to-day work and

about artistic life in the residential city of Munich at

the time.

At the beginning of March 1866, Ille was promised an

audience with the king. But in mid-March the royal

adjutant informed him that the king was so overwhelmed

with political business that he could not receive the

painter, but after the completion of the new

picture of Hans Sachs, the king might take the

opportunity and have the pleasure of getting to know

him. Ille found the cancellation of the royal audience

humiliating, mainly because it had been delivered by a

domestic. However, in mid-December, Ille reported that

the court secretary Lorenz von Düfflipp conveyed the

king's "great satisfaction" with the Hans Sachs painting

and gave him the order to "paint a picture, in the

manner of the 3 previous paintings, of the old Nibelung

legend from Norse mythology". Ille's reaction was

"half happy and half grieved". Over the next few days,

he read up on the Nibelungenlied and its relationship to

the Nordic version in Hyacinth Holland's flowery

“History of German Literature”, published in 1853. He

learned that the original version of the epic has been

lost, but that the Poetic Edda has "the basic plan

sketched out here and there", which he characterized as

"very brittle, heavy and tough material". There is an

undated eight page sketch within Ille's records titled

"Das Nibelungen-Lied", in which Ille describes his

research and presents his assessement of the

Nibelungenlied: “As a national epic, it rightly claims a

very excellent rank and remains, as Franz Horn puts it,

'an eternal pillar around which brave Germans like to

gather'." The reference here is to Franz Christoph

Horn's book The Poetry and Eloquence of the Germans from

Luther's Time to the Present. The sketch shows that Ille

was well acquainted with the German version of the

legend. The royal commission, however, was about the

representation of the Nordic variant. Richard Wagner's

"Ring" tetralogy, based on Nordic myth, was likely

tacitly behind the royal request. In January 1867, Ille

read the relevant sources of Nordic mythology.

All the while Ille kept company with

Harbni-Gesellschaft, a Munich association of

culture-loving and charitable people founded in 1850.

Their playful rituals were reminiscent of the baroque

language societies: all members of the association,

posing as a knightly order, assumed knight names; Ille's

nickname was Eduard Wörgl von Brixlegg. His Hans Sachs

picture was duly honored in thier circle. Incidentally,

he learned that the king had spoken of him and his art

in a "completely exalted" manner. The Court secretary

Düfflipp informed him again that the king was extremely

satisfied and has the intention of speaking to him; an

audience had been reserved for the next few days. This

time, however, Ille was skeptical. In a diary entry on

March 7th, he wrote: "I want to see if the king really

receives me this time! I'd love it, but I won't believe

it until I'm there.” He remained in anticipation at

home, but had to note: "No king's call rang out to me".

And a day later he thinks he knows why: the king's bride

Princess Sophie was reported to be ill, "which is

probably why he doesn't see me". However, this may be a

false conclusion, since the extremely shy Ludwig often

avoided contact with strangers and put forward all sorts

of excuses. While Ille continued to work on a painting

of the Thirty Years' War, he further deepened his study

into the Nibelungen material, reading Wilhelm Grimm's

heroic songs, Karl Simrock's translation of the Edda,

and excerpts from the sources with the still hopeful

thought "that I am well in the saddle if the king

calls.”

|

|

The Berg Palace— Berg Schloss, circa 1886 |

|

At the end of March, Ille examined the illustrations

Ludwig Schwanthaler created for the northern gable group

of Walhalla completed in 1842 - as a model for his

picture of the Niflunga Saga. His work on the Sigurd

painting began in May. Ille was then busy with the study

of Norse weapons to create an authentic atmosphere. In

September he came to the main picture of the complex,

the assassination of Sigurd, which he painted early in

the morning “with seriousness and zeal”. In October a

cabinet servant inquired when the king could get a

photograph of the picture – which upset the artist

greatly. In this respect, the information sent by Hofrat

Düfflipp News that the king was satisfied with the

photographs, certainly had a reassuring effect. His

friend Hyacinth Holland also looked at his picture “very

approvingly”. On December 3, Ille noted in his diary

that he celebrated the "completion of my picture".

35 official photographs of the

"Niflunga"-picture were made. On December 18, a

great sigh of relief was felt in his beloved Harbni

Club, as his friends congratulated him on his new

picture cycle. The year of completion is found at the bottom

right of the picture next to the Artist's signet: 1867.

After Ille had created the final image in the series of

legends, the "Parzival" painting, the king wished the

painter to depict the life of Louis XIV of France. But

Ille refused - in all deference, because he was

reluctant to paint the destruction of Heidelberg and the

devastation of the Palatinate by the French General

Mélac. He even accepted the king's disfavor for this.

But the king was apparently on Ille's reaction prepared.

He told Leinfelder that he was not ungracious, as Ille

had feared, "because" - literally - "he could have

expected something like that from Ille's stubborn head".

Nevertheless, he does not seem to have forgotten Ille's

refusal, because the next royal commission came five

years later. Now, with unmistakable irony, the king

asked the artist whether he would now be “so gracious”

as to decorate the dressing room in Neuschwanstein “with

pictures from poems by Walther von der Vogelweide”. Ille

was certainly happy, but this joy was somewhat clouded

by the king's impatience. In the autumn of 1880, the

king sent a letter via the court secretary to all the

painters involved in painting the palace, informing them

that “his Majesty would arrive at 12 o'clock on Christmas Day" to

Neuschwanstein. By then, all pictures should be finished.

So Ille needed the help of a painter friend to implement

the color sketches.

The literary historian Hyacinth Holland, who survived his friend Ille by

15 years, in his obituary, characterized the style of

the Niflunga-picture cycle, emphasizing the

"architectural framework strictly adapted to the

respective subjects and times" and the "continuous,

highly attractive juxtaposition within the pictorial

narrative". It surpasses the other picture-cycles in

terms of the number of scenes. "Tannhäuser" offers 5,

"Lohengrin" 11, "Hans Sachs" 9, and "Parzival" 19

individual scenes, while the Niflunga-picture groups 21

individual scenes in a multi-subdivided, columned hall.

The structure of the picture is strictly symmetrical. It

consists of three levels, a frieze, a middle level and a

lower level with large painted scenes on a base. The

emblem tradition emerges: the inscriptio in the middle

of the picture, the picturae on three levels, the

subscriptio at the bottom edge of the picture, and in

the names distributed across the picture. The text

embedded in the base explains the seven scenes above it,

shown on the lower level, with quotations from Simrock's

translation of the Edda. The frieze is

demonstrably based on Ludwig Schwanthaler's Walhalla

Frieze as the most important marble gable group since

antiquity, as Albert Müller 1865 in his monograph on

Walhalla states. The theme of the Walhalla frieze was

the Teutoburg Battle. With Schwanthaler, Arminius is the

central figure, with Ille, Odin, the father of the gods.

Oddly enough, he and the others depict Nordic gods in

ancient robes in classical fashion. "Niflunga-Saga" is

not a watercolor, as often stated, but a tempera

painting, using a technique in which paint pigments are

bound with a water-oil emulsion. A big advantage of

Tempura is its resistance to aging and its slow drying

that allows for longer rework.

|

|

|

|