Passages in the Poetic Edda (1877)

by M. B. Richert

[Försök till belysning af mörkare och oförstådda ställen i den poetiska Eddan]

Translated from the Swedish

by William P. Reaves © 2014

|

This article authored by Mårten Birger Richert in 1877, intending to shed light on some of the dark and obsure passages in the Eddic poems, remains influential even today. Richert's conclusions continue to be cited in modern Old Norse dictionaries and scholarly literature. While Richert sought to illuminate many such passages, including: Hávamál 13, 32, 33, and 41; Hymiskviða 2; Álvissmál 5 and 6, Vegtamskviða 14, Grippisspá 26; Reginsmál 4; Fafnismál 5, 21 and 37; Atlakviða 15, Guðrunarkviða I, 26; and Guðrunarkviða III, 11— presented here in its entirety is his interpretation of Hávamál 104-110 and a portion of his observations on Hárbarðsljóð 13. In his commentary to Hávamál (Published by the Viking Society for Northern Research, 1986), David A. H. Evans says: "For the story of Óðinn's theft of the mead of poetry from the giant Suttungr by seducing the giant's daughter Gunnlöð, see Snorri's Prose Edda (Skáldskaparmál ch. 5-6) and Hávamál st. 13-14 above. Richert p.9ff. suggests that Hávamál 104-110 imply a version where Óðinn arrives in Suttungr's halls as a seemingly respectible wooer and goes through a marriage ceremony with Gunnlöð." |

|

|

|

The Marriage of Odin and Gunnlöd

Hávamál 104, 1-2:

Vel keypts litar

Hefi ek vel notit

As is well known, the difficulty deciphering this passage lies in the

word litar. Bugge states (p.

55): “All explanations of the common word

litr seem forced.

Egilsson understands

litar as a sideform to

lutar, hlutar; this is

unacceptable, but perhaps we should amend to

lutar.” Bugge further

mentions Petersen’s and Lüning’s emendation

lidar, intended as genitive

of a masculine líðr, drink,

of which, however, he rightly remarks that the intended Norse word

is

líð, which is

neuter as are the corresponding forms in Old Saxon and Old High

German. After Bugge published his edition of the Edda, he has took this

passage into consideration anew in

Årbøger for Nordic Old kyndighed

1869 ("Afterword to my version of the Sæmundar Edda” p. 251, 252) and as

a result of the investigation, concluded that

litar should be regarded as

standing in the place of hlítar.

Hence, in his second edition Grundvig has provided

litar with a diacritical mark

over the i and in the remarks on p. 210 for Hávamál

107 has informatively stated that, in agreement with Bugge, he

interprets the passage thus: "(h)lítar vel hefi ek notit velkeypts

(drykkjar).”

In Zeitschrift für Deutsche Philologie I, 413, Möbius translates this

as: “I had the advantage of my transformation (into a snake), of my

well-earned shape” but Bugge objects to this, citing the reason: “I

don’t see how Odin’s transformation into a snake can be called “velkeyptr”.

Simrock’s interpretation “Schlauer

Verwandlungen Frucht erwarb ich"

('the fruit of sly transformation I acquired') is based on the same opinion of

litar. Winkel Horn’s, like Möller’s translation assumes the premise

of the text change from litar

to líðar (or rather

líðs). Hjort translates:

Vel monne jeg veltjent

stilling nytte,

and Afzelius even freer:

Dyrköpta sängen

väl har jag njutit.

[The dearly bought bed

Well, I have enjoyed.]

Lüning (p. 282) and Holtzmann (pp. 79 and 115) read

litar as the genitive of the

common noun. litr, color,

appearance, beauty, although they consider the interpretation highly

uncertain and thus point out other ways in which they tentatively sought

to interpret the text.

A previously completely overlooked particularity seems to me to be

decisive in regard to the correct interpretation of the difficult phrase

vel keypts litar.

I believe attention has only

once been called to what I refer and that the objections put forth by

Bugge against any explanation of

litar from “the common word

litr” shall lose their foundation.

The

presentation of the episode about Odin's journey to Suttung and the

acquisition of mead with the help of Suttung’s daughter Gunlödd (v.

104-110) is from beginning to end told in a tone that leaves the

impression that Odin was considered a welcome suitor, who, after

successfully overcoming all the obstacles he encounters on his bridal

quest, finally gets his bride and celebrates a solemn wedding with her

in the giant Suttung halls.

There is, in my opinion, a much richer content in the verses named than

we have been accustomed to see, and that the whole narrative is far more

poetic, lively and vivid, than previously understood. The image just

described is alluded to in each individual scene of this event in Odin's

life and the expressions are selected with extreme care, so that the

style might keep its initial character throughout.

After this general account, I will proceed to a detailed explanation of

what the verses contain and point out all the specific expressions

through which allusions are made to the marital union between Odin and

the giant's daughter in the poetic narrative. To me, such expressions

are:

l. Vel keypts litar.

Litar

constitutes a poetic euphemism for Gunlödd and the epithet

keypts finds its explanation

by such terms as kona

in mey

mundi (gulli)

keypt, kaupa

sér konu, brúðkaup etc. The

qualifier vel placed before

keypts apparently corresponds

to the vel before

notit, from which a certain

uniformity of expression exists between the first and second lines of

the verse. The translation thus becomes:

Av den lyckligt (i en lycklig stund) äktade* skönheten

har jag lyckligt (till min lycka, med lycklig utgäng) njutit.

[“Of the happy (in a happy moment) wedded* beauty

I have happily (at my happiness with the successful outcome) enjoyed.”]

*) or acquired to my own advantage.

For further elucidation of the term litar, one may apply the statements made on one hand in Hávamál 93 "lostfagrir litir”, through her fair captivating appearance (face, beauty), and on the other with Gripisspá 27 "er at Heimis fagrt álitum", 28 “þótt mær sé fögr áliti”, and 29 “fögr alití fostra Heimis”. What is called (lost)fagrir litir in Hávamál 93 means exactly the same thing as with it would applying the later song’s manner of expression, meyjar fagrar älitum (:áliti). The word face (Swedish: ansigte), in its origin and basic meaning, is closely in tune with anlete (Swedish for visage, face), a recent compound which is etymologically related to litr and álit, can also be used to signify a person according to contemporary language, so that for example the expression “a beautiful face" may signify a woman who has a beautiful face. It is in all respects perfectly analogous to the Greek πρόσωπον (prosópon) which signifies person as well as face.

2. v. 108, 4—6:

ef ek Gunnladar ne nytak,

ennar góðrar konu,

Þeirrar er lögdumk arm yfir.

over whom I laid my arm.

For our objective above, every exposition of these lines is superfluous.

It may only be remarked that a compilation of this text with

vel keypts litar

hefi ek vel notit

I made good use"]

should lead to the exclusion of any notion that with litar in v. 107 something other than the

Gunnlöð of v. 108 is meant.

3 v. 109, 1: The words hindra

dags (the following day, namely the day after Odin and Gunlödd had

first shared a bed with one another), which stand in immediate

connection with the last lines of v. 108, seems to contain a definite

allusion to the evening before when Odin and Gunlödd entered into

marital relations, which upon closer inspection are found to constitute

a legal marriage term. I recall the special significance of the day

after the wedding night or the beginning of the marriage contract (thus

“the second day" of the wedding), which the term

hindradagher always has in

our provincial laws (see for example Schlyter's

Glossary to the Vestg. Law, the

Ostg. Law and Upl. Law[1]), even that of the legal significance of

it in the old laws often mentioned

hindradaghsgæf, which still

survives in our era’s morgongåva,

“morning gift”. The marriage, as we know, was not considered completely

dry, when the newlyweds arrived “baþi

a en bulster ok ena bleo”[*]

(compare the end of v. 108), and it was the day after, or the

so-called hindra dagen, the

man gave his wife the

hindradaghsgæf or, as this gift alternately in laws even called,

morghongæf. The reason for

both names appear clearly in the Upl. Law Ærfþ.B. fl. 4: “Hindra

dags um morghin þa agher bonde husfru sina heþra ok hamra morghongæf

giwa.” This legal provision opens with

hindra dags in the same

adverbial sense that accompanies this expression, when it stands at the

head of v. 109 in Hávamál.

[1] The word cannot be explained according to Schlyter's assumption (Vestg. Law Glossary p. 421) of Hin arms Dagher. Hindri is apparently an old comparative form of the pronoun Hinn hin Hitt (compare the Latin *ul-ter, ci-ter, ul-ter-ior, ci-ter-ior of pronominal-stems ul-, ci-), paralleled in German by hinter and in English by hinder, and primitive in comparison to the Swedish noun hinder and verb hindra, now that the d-sound is to be regarded as purely phonetic analogy with d or as belonging to the comparative formation (Latin -ter, Greek -νερος, Sanskrit, -taras).

4. v. 109, 2—4:

géngu hrímþursar

Háva ráds at fregna, etc.

to inquire of the High One's ráð']

Translators take this ráðs either in the sense of advice (consilium) or condition, living situation, fate. The fact that the first-mentioned interpretation is certainly incorrect, should be admitted by every one who devotes any attention to this passage and considers it in the context of the preceding and succeeding verses. But even the latter interpretion means we operate from a perception which does not fully penetrate the content. Egilsson translates fregna Háva ráds: “The condition of Odin (when he happened) to be aroused" and he is followed by a large portion of the translators. Holtzmann reads the text (p. 79) as “to ask advice of Hávi" (with the note adding the alternative reading “to inquire about Odin”), but in the commentary (p. 116) mentions only one interpretation: “Háva ráds at fregna, to inquire of Odin’s fate (Egilsson, Lüning)”. In my opinion, this ráds must be taken in the narrower sense demanded by the entire context that otherwise applies to this word in the Edda songs and in many other places in the ancient literature. The expression ráð seems to me to be intentionally selected in order to constitute a continuing allusion to the peculiar role which Odin performs in this love story. Comparing Gripisspá 45:

anú Gúdrúnu

góðra ráda

and the Brot af Sigurdarkviða 3:

fyrman hon Gúdrúnu

góðra ráða

would well apply, to give a correct idea of what is meant by Háva ráðs. That ráð in this place translates as condition, fate in general would be in my mind to give the word too broad a meaning. I consider this to be an expression of marriage or the married state, when the frost-giants thus went to inquire of Odin’s condition as a newlywed husband or in other words, wanted to learn the final outcome of his adventurous bridal quest (inform themselves as to the outcome of Odin’s marriage). Regarding the frequently occurring use of the word ráð (singular as well as plural), in this sense, see Cleasby-Vigfusson p. 485 and Fritzner p. 501 (ráð 9). Compare also Fritzner p. 502, under the word ráðahagr. In Vestergötland, the author has heard råd (ráð) used in such a way that “the girl has now received råd," that is received a suitor or fiancé (Rietz records no such sense for råd). Similarly the partic. rådd in the same sense as häfdad, lägrad. Compare Rietz p. 547, rå 2.

Regarding the conceptual development that took place in the noun ráð, when it received special significance formed from the word’s more general sense, reference can be made to two enlightening places in Alvissmál, namely v. 4:

Ek mun bregða,

þvíat ek brúðar á

flest um ráð sem faðir.

['I will break it;

for o’er the bride I have,

as father, greatest power (ráð).']

And v. 5:

Hvat er þat rekka,

er í ráðum telst

fljöds ens fagrglóa?

['What man is this,

lays claim to power (ráðum) over

that fair, bright maiden?']

In the word ráð, the intrinsic general sense of power and authority, the right to rule over someone or something, finds its specific application here in regard a guardian's authority over a marriageable girl (also compare the common expression "ráða giptingu konu"). As soon as a woman left her father’s home, this sort of ráð passed to her husband, who received the so-called "husband’s authority". It is therefore quite natural that in other cases ráð was used with special allusion to the husband's right to determine and decide in relation to his wife and family (compare the basic meaning of the German Heirath and verheirathen) and thus even came to denote the married state, marital status.

5. v. 110, 1—3:

Baugeið Óðinn

hygg ek at unnit hafi,

hvat skal hans trygdum trúa?

gave, I believe.

Who will trust in his faith?"]

The words baugeið and trygðum give the impression that Odin had sworn allegiance to Gunlödd whether this is taken as a marriage engagement and oath of fidelity or as a solemn pledge of a genuine union. Specifically in regard to the expression baugeið, we can compare ones from the well-known old prose literature vinna eið at baugi, vinna eið at stallahring, and Atlakviða v. 30: eiða svarða — at hringi Ullar. Of the significance of such an oath, see also R. Keyser, Nordmamdenes Religionsforfatning i Hedendommen (in Collected Works, Kristiania 1868 p. 344 and following); Svend Grundtvig, Om de Gotiske Folks Våbened, Kobenhavn 1871 p. 46; O. Vig, Norges Sagnhistorie, Kristiania 1857 s. 193, 194.

6. v. 110, 4—6:

Suttung svikinn

hann lét sumbli frá

ok groetta Gunnlödu.

out of his sumbl,

and made Gunnlöd weep']

These lines compared with the immediately preceding ones indicate that Odin was

guilty of what in Sigrdrifumál v. 23 is called trygðrof, and that he thus

appeared as eiðrofa. See Helreið Brynhildar v. 5 and Brot af Sigurðarkviða v.

16. Compare them with Sigurðarkviða’s svíku hann i trygð in the prose

conclusion. Odin deceived his intended giant father-in-law as well as the

giant’s daughter Gunlödd, which, even if for a short time, was considered his

bride.

The word sumbl occurs not only in the sense of beverage (Álvissmál 34, and in a

few places in Snorri’s Edda, concerning which see Egilsson) but more commonly in

the sense of drinking feast, festive liquor (Hýmiskviða 2; Lokasenna 3, 4, 7, 8,

65— thereof see Egilsson sumbl and sund). One could well ask the question, how

far this sumbl could be taken in a twofold sense and if the whole expression

were purposely chosen so that its meaning would not be limited and definite.

Such vague expressions, which give rise to double entendres or puns, are

encountered in several places in the old Eddic songs.

The passage could either be translated: He left Suttung deceived on the drink

and Gunlödd drenched in tears (weeping), or: He left Suttung deceived at the

feast (wedding feast) and Gunlödd, etc: i.e the conclusion was the same,

that Suttung walked away from the feast deceived, etc.

The first three lines of v. 105:

Gunnlöd mér um gaf

gullnum stóli á

drykk ins dýra mjaðar

on a golden seat,

a drink of the precious mead']

and the last of v. 104:

mörgum orðum

mælta ek í minn frama

í Suttungs sölum

I spoke to my advantage

in Suttung’s halls']

also indicate also that Odin, when he came to Suttung’s abode, was not only

treated as an honored guest, and as such got a place to sit on the golden

high-seat, where he sat and drank opposite the host, but also during a drinking

feast (where the Hrimthurs, which according to v . 109 went “ens hindra dags"

to Odin's hall “Háva ráðs at fregna" should have been present either as guests

or as belonging to Suttung’s household), when the conversation arose with the

others standing by while he used every opportunity offered to place his words

well, thereby promoting his cause (in minn frama). Of course, Odin laid

these not least on Gunlödd herself, whose heart he soon conquered by fair words.

The connection between them was contractual and even solemnly confirmed by

baugeið and trygð (v. 110). One drank to honor the ceremony (compare the

expressions drekka brúðhlaup I. brúðkaup), and thereby it

seems to have gone so well, that the drink, which was served at the feast to

honor the groom, consisted of nothing less than the skaldic mead. It was also

just that in order to get possession of it, Odin had to appear as the suitor of

the giant's daughter and solemnly celebrate his union with her. On other

occasions, it would have been unlikely that such a precious drink (compare v.

105, 3 and 140, 4-5 drykk ins dyra mjaðar) would have been offered to

the newly-arriving guest, and that he would have had to settle for lesser

varieties of mead.

We find here a complete counterpart to the myth presented in Þrymskviða of

Thor's journey to Jötunheim. Like Thor, Odin departs for the world of the

giants, in order to seek and to gain possession of a thing important beyond

measure for him and all of the gods. The goal of Odin's journey is mead, which

is the equivalent of the hammer in the former myth. To attain his goal, he

avails himself in the same way Thor does of cunning to enter into real

relationship with giant offspring. While Thor plays the role of the bride, Odin,

however, appears here as the groom. For the celebration of the feast and the

sealing of the genuine ceremony, here the mead is brought forth and there the

hammer. Both gods take possession of a long-desired object whose precise

presentation has been the goal of their strivings and the precalculated final

scene of their extraordinary behavior. The inglorious end to the troublesome

giant woman's persistence whose narrative forms the conclusion of Thrymskvida

(v. 32) also invites an opportunity for comparison:

hon skell um hlaut

fyr skillinga,

enn högg hamars

fyr hringa fjöld

["She got a blow

instead of skillings,

a hammer’s stroke

for many rings"]

And the depiction of Gunnlödd’s unhappy fate in Hávamál (v. 105):

Ill iðgjöld

lét ek hana eptir hafa

etc.

I made her afterwards']

and v. 110:

hann lét—

—groetta Gunnlödu.

—Gunnlödd weep']

Regarding the union in question between the gods and the giants’ kin, Njörd’s

relationship with Skadi, and Frey’s with Gerd, and so on, may also be recalled.

The myth of Odin’s journey to Suttung for acquiring the mead there is also

spoken of in Snorri’s Edda (Bragaræður 57, 58), where it is clad in prose form

and presented far more extensively than can be the case in these few verses of

Hávamál. It seems to me, however, that the short and brisk narrative in the

current passage of Hávamál in several respects bears the stamp of being more

original and unadulterated than the narrative in Snorri’s Edda. The latter knows

nothing of Odin’s baugeið and trygð and Gunlödd’s bitter grief and says nothing

about how the frost-giants ens hindra dags went Háva ráðs at fregna

etc. According to the prose narrative in Snorri’s Edda "fór Bölverkr"

(Bölverkr goes), as soon as he entered in through the mountain “þar til sem

Gunnlöð var” (to where Gunnlödd was), without ever seeking Suttung

himself, and the entirety of Odin's case was secretly discussed between Odin and

Gunlödd alone, whereas Hávamál has Odin seek out her giant father (“enn

aldna jötun ek sótta”, the old giant I sought) and he appears wholley

undisguised "í Suttungs sölum," (in Suttung’s halls) where he, through

his wisdom in words and actions finally gets so far that Gunlödd gave him "gullnum

stóli á drykk ens dyra mjaðar" (a drink of the precious mead on a golden

seat.)

|

I believe that the current myth in question, which is briefly touched upon also

in Hávamál v. 13, 14 and 140 and in Sigrdrífumál v. 18, not only gains a deeper

explanation through the foregoing analysis than it previously had, but is also

presented in greater originality.

Already in v. 105, Odin says of Gunlödd:

Ill iðgjöld

lét ek hana eptir hafa

síns ins heila hugar

síns ins svára sefa

I made her afterwards

for her whole soul,

her fervent love.']

and hereby conforms closely to the end of v. 110: hann lét groetta Gunnlödu ('he made Gunnlödd cry'). In several other places, the verb groeta serves to express the sorrow and grief that the loss of a spouse or betrothed evokes in a woman. Compare for example Helgakv. Hundingsbana II, 30:

þvíat ek hefi naudigr

nipti groetta

['For I have been forced

to make my sister weep']

and Lokasenna 37:

mey hann ne groettir

ne manns konu.

['he makes no girl weep,

nor man's wife']

See further Egilsson p. 270 and compare Rietz p. 218 gröta and Aasen p. 250 greta.

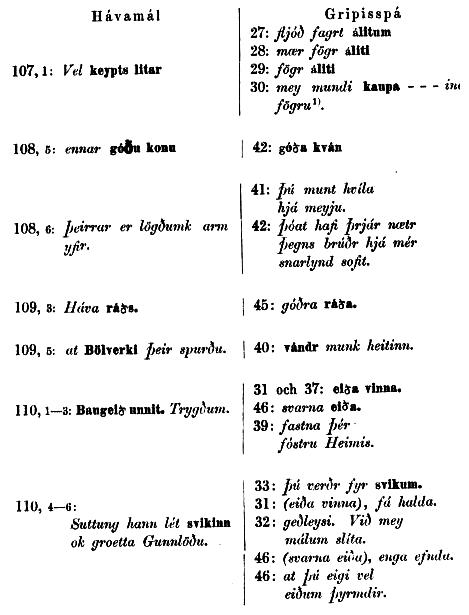

In order to extend support, to some degree, for my interpretation of the passages in Hávamál reviewed above and the related exposition of Gunlödd’s myth, I will finally refer to Gripisspá, where the depiction of Sigurd’s visit to Heime and his wooing of Brynhild up to and including v. 27 of many essential places resembles Hávamál 107-110 and many expressions are almost the same as those in the latter passage. The intended points of contact and comparison can be illustrated in the following manner:

*) The compilation of these cited expressions from four successive verses of

Gripisspá likely indicate, that the transition from the expression “kaupa

mey fagra áliti l. álitum”

to “kaupa (fagrari)

lit” (i.e. purchase of beauty, the

beauty herself, i.e. the girl with the fair appearance) cannot remain considered

to be unconnected in the literature.

As a conclusion to my attempts made here to

further illuminate and interpret the actual content of the account of

Gunnlödd’s myth in Hávamál 104-110, I will now to take up the issue of

the relationship between the beginning of the narrative in v. 104 and

the closest foregoing verses. Luning, Möbius and many other editors of

the Edda set a great dividing line between verses 103 and 104, in order

to thereby give notice that a stand-alone and more independent section

of Hávamál has been created. Bugge objects, p. 55 (in the note to v.

104): "R (i.e.

Codex Regius) does not indicate that a new section begins

with this verse" and has also ruled, in the case this line. To me, it

seems so much clearer that no such dividing line should be contemplated,

on the contrary v. 104 and the following verses stand in the closest

connection with what the previous verses contain. The whole story of

Odin's visit to Suttung and courtship to Gunlödd has evidently been

provoked by some general observations in v. 103. Namely, it states there

in the final lines:

fimbulfambi heitir

sa er fátt kann segja,

þat er ósnotrs aðal

who little has to say:

such is the nature of the simple'.]

and it is precisely these words, which gave reason for Odin in v. 104 to break into the speech about the visit to Suttung, of which he says:

Enn aldna jötun ek sótta,

nú em ek aptr um kominn,

fátt gat ek þegjandi þar.

['The old Jötun I sought;

now I am come back:

little got I there by silence.']

The last of these lines serves to elucidate and give evidence for the accuracy of, what is explicitly stated in the three lines which end v. 103. The reasoning is apparently this: I have just said "fimbulfambi heitir etc." (a great fool, I was called) "and that this opinion was correct, I wish to prove by relating one episode from my own eventful life. Namely, once I visited a mighty giant and “I won little with silence there", i.e. I would have accomplished little if I had sat there like a "fimbulfambi" and kept quiet. If I had, I would have ill accomplished my delicate and adventurous mission and certainly not returned successfully (“nú em ek aptr um kominn”), much less in possession of the precious mead. What I just said about the benefits of being "sviðr um sik" (discreet, sensibly calculating) and "málugr" (talkative. Compare the rule of wisdom in Hávamál v. 63) and to "opt góðs geta" (often leading the conversation, what is agreeable), also found its application "í Suttungs sölum," (in Suttung’s halls) because there mörgum orðum malta ek i minn frama (it was the precisely in this way that I spoke a lot and realized that by placing my words, I could promote my case). This whole episode is thus in its proper place right here and is connected with the previous episode in exactly the same way as the story of the adventure with Billing's daughter in its place. Verse 96 starts:

þat ek þá reynda,

er ek í reyri sat

etc.

['That I experienced,

when in the reeds I sat.'

etc.]

and thus, together with the following verses intended as an illustrative example of the correctness of the wisdom of the rule that Odin previously stated. In the same respect, we can also compare considering the idea-associations and connections between the story and the context of the narrrative in v. 13 and 14 and general statement contained in v. 12.

In Sveinbjörn

Egilsson's Lexicon Poeticum (1932,

p. 660), under the word

ögur, which is listed as "of uncertain meaning" [af usikker

betydning], occurs the following definition:

"den rimeligste er Richerts opfattelse, = byrde (madkurven

som Tor bar)."

which reads,

"The most reasonable is Richert's conception, = burden (the meal-basket that Thor bears)."

This is confirmed by Beatrice LaFarge in her Glossary to the Poetic Edda (1992), which says:

"ögurr m. burden (Richert)"

Here are Richert's opening remarks on the word ögur in Hárbarðsljoð 13:

Hárbarðsljoð 13, 3:

ok væta ögur minn.

|

Holtzmann p. 232 describes the proposals put forth from different directions for the emendation of the misunderstood word ögur. Bugge’s astute guess dögurð (adopted by Grundtvig) is without comparison the most noteworthy. The passage seems to me, however, to be explainable without emending the ögur of the manuscript. According to Bugge the word is "otherwise unknown" but, as far as I know, it appears in another place in the Edda, namely Völundarkviða 41 as part of the compoundögurstund. The German word root ag = indoeurop. agh, gr. άχ (or with nasal sound άγχ, parallel with the German ang, shape), has as its primary meaning “clamp, press, put pressure on”. Thus in various Indo-European languages we find a variety of word formations, which denote pressure, burden —partially in an outer, physical sense, but also in an inner, spiritual sense (= oppression, anxiety, fear). In my opinion ögur inögurstund can be taken in the latter (inner, spiritual) sense, while the more original physical sense of weight, burden explains the word in Harbardsljod: ögur minn therefore denotes my burden, what I carry, an expression that finds its explanation in v. 3:

|

For a detailed analysis of Hárbarðsljóð 13, see:

THOR'S BURDEN

The Trouble with Translating

—minn ögur— in

Hárbarðsljóð 13

[HOME]