THE FRAU HOLLE LEGENDS

THE PERCHTAN DANCERS

of Salzburg, Austria

An eyewitness account of 1907

Published with Photographs in

The Wide World Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly of True Narrative 1908

By Mrs. Herbert Vivian

|

The Perchtentanz is named in honour of Perchta, another name for Holda or Frigga, Woden's consort and the mother of the gods. Although banished from many of her ancient haunts by rude civilization and unbelief she still clings to Salzburg and parts of the Tyrol, where the peasants not only believe in her, but fear her. Perchta means the Splendid, the Magnificent One. She may be seen, they say, wandering through the great fortress of Salzburg at dead of night. Towards the beginning of the year, in the guise of a tiny, wizened witch, with gleaming eyes, long hooked nose, and wildly , tangled hair, she lurks at cross-roads, waiting for travellers. When one approaches she greets him with her friendliest smile, and holds out to him a black cloth. If he takes it he is done for, and will certainly not survive the year; but if he brings out his crucifix and says, "Dame Percht, Dame Percht, throw the cloth on the earth," then every joy and blessing will come to his house. If Perchta shows herself in a stable, sickness and death are sure to follow, unless the careful peasant hangs up a bunch of consecrated St. John's wort, a potent herb in these lands. On other occasions the goddess gathers all the unbaptized children round her, and sweeps through the country at the head of the band. At Christmas-time a spoonful of every dish used to be placed on a fence, or a gate, outside the house as an offering to this much-dreaded lady. One of the strangest things about Perchta is that she has a double nature. Sometimes she is the soul of goodness and charity, at other times she is full of hate and malice to mankind. Men are fascinated by her, but their feelings are mixed, and fear is mingled with longing—fear on account of her uncanniness, and longing because of her wondrous powers. Perchta has her troops of followers, strange beings half-way between mortals and immortals. These do not live among the children of men, but appear amongst them at such times as Advent and the Feast of the Three Kings. Like Perchta herself, they are divided in disposition. for some are good, kindly creatures, such as the "beautiful" Perchten [Schon Perchten]; while others, like the Schlachten Perchten, are wild, irresponsible, malicious things. They are more felt and heard than seen. In swarms they come down on men's dwellings, and are recognised by their weird screams and laughter. They love to draw men into danger by alluring sounds and spells, and to punish undiscovered crimes. The Perchten dances originated among the peasants of the mountains, who desired to imitate these mythological beings, but of late years the performances have seldom been seen. In 1867 there was a display, and then nothing till 1892. The cost of the affair is so high that only the rich farmers can afford it, for the head dress of a " beautiful" Percht sometimes costs between thirty and forty pounds. On the day of the fair I had to be off early in order not to lose any of the fun. The special train started soon after seven, and on Salzburg station I found a collection of the notabilities of the district — mayors in frock-coats and top-hats, local squires and magnates in the becoming Tyrolese costume of green tweed coats and breeches, and jaunty green felt hats adorned with cords and a saucy little eagle's feather tucked into the band at the back. Past marvellous mountains and through wonderful passes we went, till we found ourselves in the most romantic part of the Tyrolese Alps, just halfway between Dachstein and the Gross Glockner. A jingling little victoria took me up to the fair ground. Here, although so early in the day, people were running excitedly about, flags were flying, and prize cows were lowing. Women in quaint garb—black patent leather sailor hats and very big white aprons— and men in green loden wandered round, exploring with immense interest the little wooden booths. Some bought from a redhot grill long strings of the little hot sausages [würste] so dear to the Austrian heart; others danced slow and solemn waltzes in the big summer-houses with sides open to the air. As I was quite alone and knew nobody, I had now to find out when the Perchten dances took place and to try to wheedle someone into allowing me to see the dress rehearsal and take some photographs. Just then I caught sight of several young men in top-hats and frock-coats adorned with huge rosettes. Nobody could possibly put on a silk hat from choice on a roasting summer day, I argued, so they must have something to do with the show. With some trepidation I pounced on one of them, who wore a benevolent expression, and begged for information. Nobody could have been kinder, but at first it seemed as if he could not enlighten me much. I became almost tearful at the idea of returning with no spoils of war, for I knew well that once the Perchten arrived at the fair there would be no getting anywhere near them, and crowds at least four deep would separate my camera from its prey. Presently, however, he became more hopeful; a friend of his was arranging the dances, he said, and he would see what could be done. With as many apologies for bothering him as I could muster in German I retired to an open-air cafe, where I tried to while away the period of waiting by drinking many coffees with whipped cream floating on the top. |

|

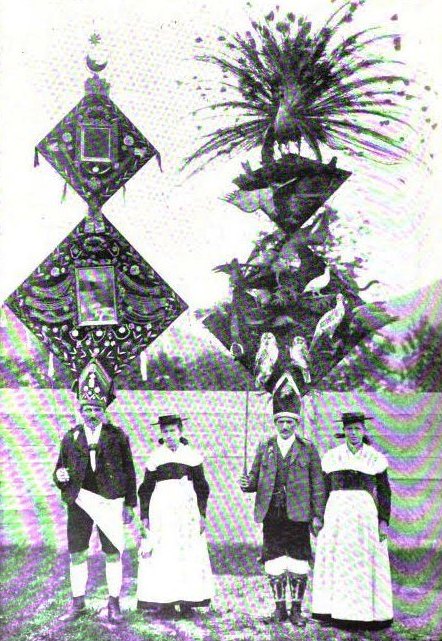

Time was getting on, so I wandered round the show again, gazing at immense cart-horses, prize oxen, and the giddy merry-go round. To my relief I caught sight of my young friend (who I now discovered was the sub-prefect of the place), accompanied by another cheerfullooking youth. "Here is the gentleman who is arranging about the dances," he said; "he will tell you what can be done." The cheerful young man had evidently had little experience of the trials that befall a photographer, but after some persuasion he agreed to let me see the dress rehearsal, which was to take place at a farm some little way off. "Meet me at the bridge at three," he said, "but I shall not be dressed like this. I shall be clad in green loden from top to toe. So prepare for the transformation!" At three o'clock punctually I was on the bridge, and here I sat for some time watching the dear old town, with its wooden houses, and the great mountains all round. Presently a boy touched me on the shoulder. My cicerone had kindly sent a chariot for me, which drove me to an old farm-house on the outskirts of the town. Here I found him surrounded by a motley crew of people in masks, whom he was striving to keep in order. "Now, what do you want to snapshoot?" he said. "There is plenty of choice. Will you have a chimney-sweep, a bear, a bundle of wood shavings, or a village idiot?" Everybody entered into the spirit of the game. A rag-picker clasped his temporary wife —a man in female clothing, of course, about double his size —wildly to his arms, with shrieks of "My darling Eliza," and the village idiot sank in a huddled mass against the wall. All wore the most repulsive masks and the strangest collection of tatters, and darted about, letting off squibs, brandishing sticks, and ringing large and peculiarly penetrating bells. For all their hurry and scurry, however, they were most polite and kind to me, and were ready to pose for any groups I wanted. Presently there was a stir. The "beautiful" Perchten were arriving. Nothing could be more fantastic than the appearance of these gentlemen. The pictures describe them far better than any words of mine can do. The lower part of their costume is unobtrusive, and all one's attention is centred on their heads, which are crowned with what surely must be the most immense and eccentric head-dress in the whole world. Two diamond-shaped boards, in all some ten or twelve feet high, are covered with red velvet. On them are fixed dozens of silver watches and chains and every kind of ornament the Perchten have been able to collect or borrow—looking-glasses, artificial flowers, pictures of the Virgin, bracelets, necklaces, and coins. At the top comes a crown, above that a moon, and then again a star.

In their right hands the "beautiful" Perchten clasp a naked sword, and with the other they lead their partners — young men dressed as women. The latter were disguised so skilfully that it was almost impossible to tell whether they were really women or not, for of course there were many wives and daughters of the Perchten helping with the preparations. I remarked on this to my guide, so he immediately seized hold of the first person in woman's garb he saw, and inquired :— "The English lady wants to know if you are a man or woman. Now, let's hear which you really are." As a matter of fact, the victim was a very shy girl; and there were blushes and giggles, accompanied by squeals of delight from the crowd. The noblest of the "beautiful" Perchten wear bird head-dresses. These are large pieces of moss-covered, board, and on them are fixed every rare bird that has been shot in the neighbourhood by the Perchten and their friends. The "tafel," as they are called, are really most striking and artistic. On the top comes a large bird with outspread wings, in this case a huge peacock with a gigantic tail. Naturally these head-dresses are of a terrific weight, and have to be supported and steadied by an iron rod which is fastened to the back at the waist. I should think the poor fellows suffer for being beautiful, as the strain and the heavy load must conduce to violent headache. The back of the erection is usually covered with canvas and painted with a pastoral scene, such as the Almfahrt. A good part of the toilette of the Perchten had to be done in public, and it was rather amusing to see their wives fussing round them doing up buttons and tying strings.

First went the band, then came the "beautiful" Perchten, leading their partners with stately step and slow. The "wild" Perchten followed behind. At first they affected a certain dignity, and tried to make out they hadn't the least desire to appear more conspicuous than necessary. So, according to etiquette, the spectators and hangers-on felt it their duty to encourage them and tease them in order to extract the well-known war-whoops, whistlings, and unearthly growls and groans. However, until the wild ones reached the fair they managed to keep up an appearance of calm. Here the procession marched to the middle of the ground, where the "beautiful" Perchten (who never lose their stupendous pomposity) began treading a measure at a pace carefully adapted to their cumbersome head-gear. The crowd closed round them, wrapt in admiration of their finery. This was the opportunity of the wild, bad Perchten. They began to quarrel amongst themselves. The chimneysweep and the rag-and-bone man had a violent discussion. Evidently the insults of the latter were not to be borne, so the chimney-sweep made a wild plunge in his direction, nearly knocking over half-a-dozen old women; and they began to chase each other all over the ground, dodging in and out among the unwary spectators and executing mad leaps and bounds. The postman promptly began to flirt with the rag-picker's wife, which, of course, was not to be tolerated for an instant; so the rag-picker dropped his quarrel with the chimney-sweep and dashed off to clasp his "darling Eliza" in his arms and to punch the postman's head.

Perhaps the bear and his leader achieved the greatest success of all. He prowled around in the most stealthy manner, and got a rise out of more than one person absorbed in the performance of the "beauties." I was standing on the edge of the crowd watching them, when suddenly a huge hairy paw was put round my waist and a gruff voice said "Boo!" in my ear. In my terror, for I had quite forgotten the bear, I leapt a foot into the air and gave a piercing yell, which afforded all my neighbours the keenest delight. As a rule the "wild" Perchten like to do their "running," as it is called, at night, and the three Thursdays of Advent are the favourite time. They go round armed with whips, drums, iron kettles, big and particularly noisy bells, and a quantity of very small shrill ones. Sometimes a group of Perchten from one village meet a band from another village and warfare ensues. Indeed, on one occasion in past days, four Perchten were killed and stealthily buried by the rest. Their graves, marked with stone crosses, may yet be seen near Wagrein. In the old days the "wild" Perchten did not even fear association with the Evil One, and a fearsome tale is told by an old wife of Gastein. It was once thought that if a Perchten runner went for fourteen days before the great occasion without praying or making the sign of the Cross it would make him more agile and amusing than any of the others. So one of the performers thought it could do no real harm to try the recipe and see what would happen. When the time arrived the spectators were amazed to find one of the Perchten jumping on to the roofs of the houses and swinging himself with the greatest ease from one high point to another, till at last they could not see him at all. Something was not quite right, they thought, and hurried off to fetch a priest. The reverend gentleman was in church, but he came as soon as possible to the market-place and began to scatter his blessings to the four winds. Suddenly the agile Percht dropped from nowhere at all at the priest's feet. Naturally, there was not much of him left, but he just managed to utter a remonstrance. "Oh, sir," he groaned, "you might for once have spared me your blessing. You cannot imagine the heavenly sensation of dancing aloft on the clouds which I have been enjoying. But directly your reverence came the devil forsook me and here I am!" With that he drew his last breath.

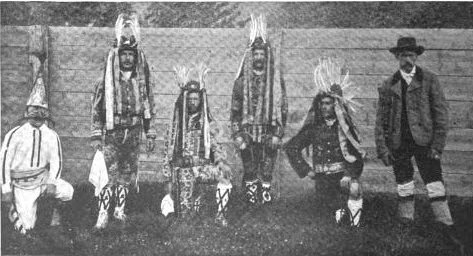

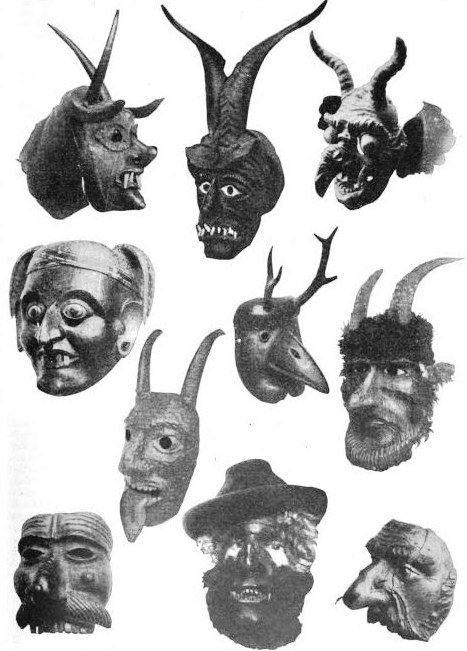

The Perchten in Pinzgau are rather differently clad. Their head-dresses, though not quite so amazing as those of Pongan, are still most curious. They consist of a round hat in the shape of a crown, adorned with tufts of erect white feathers. On either side wide, brilliant coloured ribbons fall to below the waist. The coats and knickers are of some gaudy figured stuff, and even the long white stockings are striped and worked with startling designs. Some of the masks worn by the Perchten are extraordinarily curious and frightful. In olden times the different variations of devil-masks were the most popular, and the village artists seem to have let their imagination run riot in producing the most uncanny results in these wooden faces. Animal masks, too, are popular. Long teeth and twisted horns are favourite ornaments, and a tongue lolling out of the mouth also has a good deal of success. The masks of men's heads are not unlike those used by actors in ancient Rome. They are truly grotesque, with protruding eyes, deep lines, warts, and so on. Some are fashioned like Turks, the face painted yellow, and with a gaudily-decorated turban on the head. Many of the masks are very old and extremely interesting.

When the dance at the fair was over the performers marched to the high street of the village, and there, between the two principal inns, gave another display. The kindly landlord of the principal inn, seeing me trying to find a quiet place whence to watch the antics, came and invited me to the balcony on the first floor, where I had an admirable view of the proceedings. I was indeed sorry when the time came for me to catch my train back to Salzburg, for I have rarely spent a more interesting day, or met more good-natured and merry people. In conclusion, I must not fail to express my thanks to Herr Adrian, of Salzburg, the chief authority on the folk-lore of that district, who kindly gave me many interesting facts about the Perchten out of his vast store of knowledge. |

Pinzgau Percht-tafel by Karl Adrian |

|

Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic

Mythology |