|

The Heathen Hof at Hofstaðir, Iceland |

|

Hofstaðir is the name of a

Viking era settlement, located in the upper Laxá valley in

northeastern Iceland, in use between c. AD 940–1070.

The Viking Age site consisted of a large hall-like building, several adjacent pit house dwellings, and a church (built ca. 1100). A boundary wall enclosed a 4.5 acre field, where hay was grown and dairy cattle were kept during the winter. From its first excavation, the monumental size of its central hall and its place name seemed to indicate that the settlement was a heathen cult site. From the mid-20th century, however, that interpretation was challenged, primarily because the site, although large, was much like any other farmstead. Recent archeological excavations suggest that Hofstaðir was primarily a chief's settlement, with a great hall used for ritual feasting and events. During the Viking Age, a fairly robust population occupied the site during the spring and summer. Fewer people lived there during the winter months. Founded in the middle of the 10th century, the site continues to be occupied today. |

||

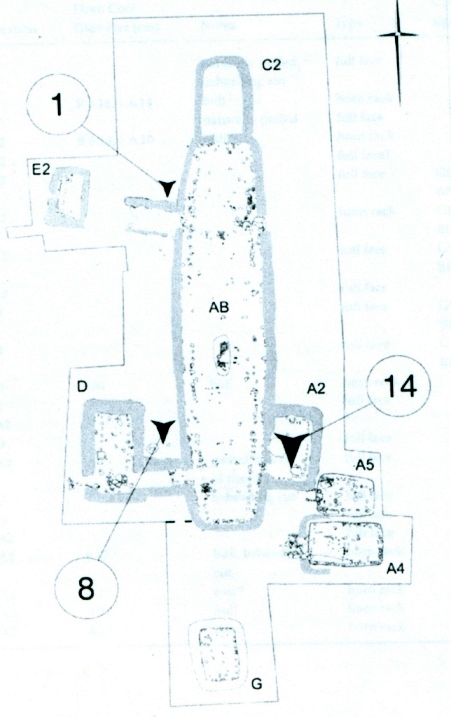

Composite Photo of the Hofstaðir site |

||

|

Structure The site's largest building is a hall, typical of Viking sites, except that, it is twice as long as an average Viking hall. At 38 meters in length, the hall is the largest Norse longhouse yet excavated in Iceland. A separate room at the north end has been interpreted as a shrine or inner sanctuary, where wooden stakes with carved faces representing Nordic gods may have been housed. A huge cooking pit is located in the southern end. A smaller building stood adjacent to the south-western side of the great hall, and a smaller ancillary room connected to the hall on the south-eastern side (See Diagram "Location and Number of Cattle Skulls" below). Based on various hints, the hall may have originally been planned as a shorter building, and only been extended to its full length as a result of a substantial enlargement near the end of the 10th century. Such a change assumes that the earlier building was planned to a skewed outline, or that substantial adjustments were made to the wall-line in the central part of the building, neither of which seems likely.

|

||

Aerial Short of Hofstaðir showing the octagonal shape of the site |

||

|

While most postholes are shallow, a small number of deeper-set postholes seem to be aligned on a regular grid. This divides the length of the building into four sections of equal length, each further divided, apparently on a unit of 1.85m, a measure, corresponding to a fathom (6 feet), often seen in Scandinavian buildings from this period. Otherwise, there seems to be little patterning in the rows of postholes, which divide the hall into three aisles. Lucas claims, many were 'obviously later insertions ...though it is impossible to phase the posts as a group' (2013, p. 70). A set of horizontal beam slots, marking partitions in the side-aisles of the main hall, may indicate individual sleeping berths or cubicles for guests. But since no such partitions are known from other comparable buildings, these beam slots may simply be joists, designed to carry the floor planking of side-aisle platforms. When partition walls occur in Viking Age Scandinavia, these consist of a line of vertical posts, which presumably supported a cladding of daub or horizontal planking. Thus this interpretation stands in stark contrast to the grand, open rooms, which appear to be the very point of Scandinavian hall buildings, as evidenced by the architectural innovations created to achieve them. The interpretation of the Hofstaðir site as a heathen temple or a large feasting hall with a heathen shrine, comes from the recovery of at least 23 individual cattle skulls, located in two distinct deposits at the southern end of the hall.

|

||

Hofstaðir site (center). |

||

|

RITUAL Animals bones found at Hofstaðir include those of domestic cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, and goats; as well as those of fish, shellfish, birds, and a small number of fox, whale, and seal. One house yielded the bones of of a domestic cat. Radiocarbon dates on animal bone range between 1030-1170 RCYBP. While a majority of the bone fragments represent the normal refuse of a Viking Age settlement, a group of cattle skulls with abnormal butchering marks found in and around the great hall display signs of ritual slaughter. Skulls of at least 23 individual specimens recovered from outside the building show signs of specialized butchery. These marks include fracturing of the frontals by a heavy and fatal blow between the eyes; and where the base of the skull is preserved, evidence of a powerful shearing blow, which would have decapitated the animal. The cattle were killed while yet standing, an immensely impractical technique, but one capable of producing a spectacular fountain of blood since the animal's heart would still be beating. Advanced surface weathering on the exterior of the skulls, combined with unweathered interior surfaces, suggest that the skulls were displayed on the outside of the building for an extended period of time, after the soft tissue had been removed or rotted away. The cattle skulls were primarily found in two clusters at the southern end of the hall, an area which generally held more artefacts, suggesting more activity (See diagram below). Eight (8) skulls were located on the south-western exterior of the hall, associated with two major entrances. The interior of an ancillary room on the south-eastern side of the hall contained 14 more skulls, along with the fully articulated skelton of a female sheep; unbutchered, it had also been killed by a heavy blow to the forehead, unlike normal contemporary practice. A single (1) cattle skull was located just north of the projecting porch at the northwestern entrance. All of the skulls were found within areas where turf walls and roofs had collapsed, suggesting that they had been suspended from the eves or the rafters where they appear. These skulls were presented in two different fashions: one consisting of the "full face" of the animal, with only the lower jaw removed, and a second comprising the "horn rack", with the entire lower face cut away, leaving only the frontal bones and horns attached.

|

||

|

Location and Number of Cattle

Skulls (Lucas and McGovern, 2007)  |

||

|

|

||

|

Where it was possible to determine gender, the vast majority of the skulls were identified as male. Where teeth remained attached, the age of death was determined to range from young adult to middle-aged adult, a pattern very different from that normally found on Viking era Icelandic farm sites. Light wear of the manidular tooth rows of the cattle found at the Hofstaðir site demonstrate that these animals were in their prime, productive years, not elderly dairy cows at the end of their run. These skulls are almost certianly those of mature bulls, which appear to be large by the standards of comparable cattle found in contemporary North Atlantic regions. The Hofstaðir animals were clearly harvested for their meat, in contrast to the local dairy profile. Dairy bulls, which are commonly raised to puberty, bred widely, and then slaughtered before they reach their full consumption potential, are rare and expensive animals in most pre-modern agricultural settings.

Radiocarbon dating on five of the skulls suggest that the animals died between 50-100 years apart, with the latest dated about AD 1000. This and the differential weathering patterns provide evidence in support of a model of recurring ritual slaughter, resulting in an accumulating cattle-head display over time, rather than a single mass killing event. Lucas and McGovern conclude that cult activity at Hofstaðir ended abruptly in the mid-11th century, about the same time a church was built, about 140 meters away. Differential weathering patterns indicate that these skulls were displayed face out on the exterior of the hall for an extended time—months or years. The anomoly, however, is that most were found concentrated in two fairly inconspicuous locales, one inside and the other in an enclosed niche between two buildings. Weathering patterns suggest that the skulls had once been mounted in more exposed and visible locations on the outside of the building for an extended time. The skulls were not deliberately buried, but found in the remains of collapsed turf structures, so the context in which they were found may indicate that they had been intentionally gathered (perhaps to be stored for the winter) before the building had been abandoned. In this light, the fully articulated sheep found inside the hall has been interpreted as a termination ritual.

All other animal burials in Iceland, identifed as

sacrifices, have either been horse or dog, not cattle.

Cattle bones are found in Viking Age burials in other Nordic

countries, but are much rarer than that of horses and dogs.

Horse burials are unusually common in Iceland as compared to

other parts of Scandinavia. Interesting in this

context, the Oseberg ship burial from Norway contained 13

decapitated horses. Other examples include the Gokstad

grave, also in Norway, and several decapitated horses

accompanying horse burials in Iceland. The horse burials in

Iceland, where they have been sexed, were all male.

Similarly, Adam of Bremen (IV, 27) describes the sacrifical

offering and display of nine kinds of male animals at a

heathen festival in

Uppsala, held every nine years. Horses and dogs, along

with human beings, are mentioned among the sacrifices there.

Thietmar of Merseburg describes a similar ceremony at

Lejre in Denmark around AD 1015, where dogs, cocks, and

humans were sacrificed. The Icelandic Sagas also offer

several examples of ritual slaughter and feasting, as well

as animals specifically kept for such purposes.

|

||

|

Also See: The Symbolism of Sacrifice |

||

|

||

|

EXCAVATION Hofstaðir was

first excavated by Daniel Bruun in 1908, who interpreted the

site as a pagan temple. The basis for his interpretation was

both the place name and the great size of the main hall. This

remained the dominant theory until the mid-20th century, when

the site was reopened by Olaf Olsen

(1965) who redefined it as temple-farm— the residence of a

chieftain who also acted as priest, presiding over religious

ceremonies there. Excavations at the site between 1992 and 2002,

led by Gavin Lucas and Thomas McGovern, resulted in the full

excavation of the long hall, and revealed new adjacent

structures. From this, it was argued that Hofstaðir was

primarily a chieftain's settlement, and that any religious

ceremonies conducted there would have been of secondary

importance to its political status, making the site comparable

to other monumental halls found in Nordic countries such as

Borg,

Lejre, and

Uppsala. The discovery of cattle skulls, slaughtered in

ritual fashion, demonstrates that that the heathen religion was

intregal to the political nature of the site. |

||

|

Sources: Lucas, Gavin and Thomas McGovern. "Bloody Slaughter: The Ritual Decapitation and Display at the Viking Settlement of Hofstaðir, Iceland." European Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 10 (1), pp. 7-30. Icelandic Viking Site of Hofstadir By K. Kris Hirst Hofstadir: Excavations of a Viking Age Feasting Hall in North-Eastern Iceland (Institute of Archaeology Reykjavik Monograph 1). 978-9979-9946-0-2, paperback $48 [Review] |

||

|

|