A Study Guide

HOME

Gróugaldur and Fjölsvinnsmál

Analogues

Otharus and Syritha

Viktor Rydberg suggested that part of the adventure that takes place between the two halves of the story told in Gróugaldur and Fjölsvinnsmál may be preserved in the tale of Otharus and Siritha, found in Saxo Grammaticus' Danish History, Book 7 (c. 1120). He believes the names of the protagonists, Otharus and Syiritha, derive from the names Óðr and Sýr. Óðr is the name of Freyja's husband found in Snorri's Edda (Gylfaginning 35), and Sýr ('sow', female pig) is a byname of Freyja herself (Gylfaginning). Rydberg suggests that she acquired this name in time of captivity among the giants.

Scholars have long known that Saxo's History contains elements of Icelandic mythology, reworked as history. However, when examining Saxo's text, it is often difficult to determine what the original form of the myth may have been. In the introduction to the first English translation of Gesta Danorum by Oliver Elton (1894), Frederick York Powell wrote:

No one has commented upon Saxo's mythology with such brilliancy, such minute consideration, and such success as the Swedish scholar, Victor Rydberg. More than occasionally he is over-ingenious and over-anxious to reduce chaos to order; sometimes he almost loses his faithful reader in the maze he treads so easily and confidently, and sometimes he stumbles badly. But he has placed the whole subject on a fresh footing, and much that is to follow will be drawn from his "Teutonic Mythology", adding "The skeleton-key of identification, used even as ably as Dr. Rydberg uses it, will not pick every mythologic lock, though it undoubtedly has opened many hitherto closed."

Britt-Mari Näsström (1995) Freyja: The Great Goddess of the North.

"Victor Rydberg suggested that Siritha is Freyja herself and that Ottar is identical with same as Svipdagr, who appears as Menglöd's beloved in Fjölsvinnsmál. Rydberg's intentions in his investigations of Germanic mythology were to co-ordinate the myths and mythical fragments into coherent short stories. Not for a moment did he hesitate to make subjective interpretations of the episodes, based more on his imagination and poetical skills than on facts. His explication of the Siritha-episode is an example of his approach, and yet he probably was right when he identified Siritha with Freyja."

In his Investigations into Germanic Mythology, Vol. I (1886), Rydberg demonstrates through a series of textual comparisons, that Svipdag probably entered the land of giants to rescue Freyja (called Menglad in Svipdagsmál) from bondage there. Like her brother Frey in Skírnismal, she is in a trance, likely induced by jötun-magic.

Otharus and Syritha, Saxo Grammaticus: History of the

Danes, Books I-IX, Book 5 (Peter Fisher tr., p. 208-210):

This man's (Sivald’s) daughter, Siritha, was so conspicuously modest

that when a large crowd of suitors flocked to her because of her beauty,

it seems she could not be induced to look upon any of them. Confident of

her self-restraint, she begged her father to grant her as husband the

man who could sweetly coax her into gazing back at him. …Then a certain

Othar, Ebbi's son, fired perhaps by his great achievements, perhaps sure

of his charm and eloquence, glowed with an unrelenting passion to woo

the girl. Though he strove to bend her glance with, his natural powers,

no art whatsoever would raise her downcast regard and he went away

marvelling at the unyielding severity he could not overcome.

There was a giant who had the same intentions, but when I discovered his attempts equally ineffective he bribed a woman to become the maiden's attendant for a period and secure her friendship. Eventually she found a cunning excuse for departing the palace and inveigled Siritha far from her father's house. Soon after, the giant rushed on her and carried her off to his narrow den on a mountain ledge. Some are of the opinion that he assumed female shape, whereby he craftily lured the girl away from home and finished off as her kidnapper.

When Othar learnt about this, he ransacked the depths of the mountain in order to track down the girl, discovered her, slew the giant and led her away with him. The creature in his attentions had bound back her hair into a tight knot so that the bunch of curls was held in a twisted mass, a tangled cluster which no one could unloose except with a knife. Again using various incentives, Othar attempted to make the girl look at him, but when he had long tried to attract her drooping eyes and nothing happened to accord with his wishes, he abandoned his scheme. He could not bring himself to use the girl lustfully, for he was unwilling to stain with disreputable intercourse a daughter of noble parentage.

After she had hurried blindly for a long while

through the twisting, paths of the wilderness, she chanced to arrive at

the hut of an enormous woman of the woods. Assigned to graze her herd of

she-goats, Siritha once more enlisted Othar's help to get free,

whereupon he assailed her with these words:

"Don't you prefer to take my advice,

join in a union to match my desires

rather than stay with this drove and tend rank-smelling kids?

Rebuff the hand of your evil mistress,

take to your heels from this savage keeper ,

come back with me to the friendly ships

and live in freedom.

Abandon the animals in your care,

refuse to drive these goats, and return .

as the partner of my bed, a prize

to suit my longings.

As I have sought you with such eagerness,

turn upward your languid eyes; it's an

easy movement to raise your bashful

face just a little.

I shall set you again in your father's home,

restore you in happiness to your tender

mother, when once you disclose your gaze

at my gentle prayers.

Because I have bourne you from the pens of giants

more then once confer the reward

in pity for my long-lasting, arduous toils

and relax your rigour.

Why have you taken to this crack-brained madness, preferring to herd a

stranger's flock, and be reckoned among the slaves of ogres instead of

arranging a harmonious, sympathetic marriage-agreement between the us?"

None the less she did not want her chaste and constant mind to waver by

staring at the world about her, but continued to preserve the same

inflexible habit and kept her eyelids motionless. When Othar therefore

was unable to incite the girl to look at him even after earning it with

a double service, weary with humiliation and grief he went back to his

fleet

After Siritha had ranged far and wide as before over the rocky

landscape, she stumbled in wanderings on Ebbi’s house where, ashamed of

her threadbare, needy condition, she made out that she was the child of

paupers. Although she was pallid and clad in a meagre cloak, Othar’s

mother observed that she was of high pedigree and. having seated her in

a place of honour, kept the girl with her, treating her with respectful

courtesy. The girl’s beauty revealed her nobility and her tell-tale

features bore witness to her birth. On seeing her, Othar asked why she

buried her face in her robe. As he wished to be more certain of her

thoughts, he pretended that she was to become his wife, and as he into

bed gave Siritha the lamp to hold. Since the light was nearly out, she

was tormented by the flame creeping close to her skin, yet she gave such

a display of endurance that she restrained any movement of her hand, to

make believe that she felt no annoyance from the heat. The warmth

inside her overcame the temperature outside and the glow of her longing

heart checked the scorching of her flesh. Finally, as Othar told her to

take care of her hand, she shyly raised her eyes and turned her gentle

gaze to his. Straight away the pretended marriage became real and she

ascended to the nuptial bed as his bride.

|

by Ferdinand Leeke

|

Dan 7.4.1 (p. 188,3) |

Siwald's daughter, Sigrid, was of such excellent modesty, that though a great concourse of suitors wooed her for her beauty, it seemed as if she could not be brought to look at one of them. Confident in this power of self-restraint, she asked her father for a husband who by the sweetness of his blandishments should be able to get a look back from her. For in old time among us the self-restraint of the maidens was a great subduer of wanton looks, lest the soundness of the soul should be infected by the licence of the eyes; and women desired to avouch the purity of their hearts by the modesty of their faces. Then one Ottar, the son of Ebb, kindled with confidence in the greatness either of his own achievements, or of his courtesy and eloquent address, stubbornly and ardently desired to woo the maiden. And though he strove with all the force of his wit to soften her gaze, no device whatever could move her downcast eyes; and, marvelling at her persistence in her indomitable rigour, he departed. |

|

Dan 7.4.2 (p. 188,15) 1 Eiusdem rei cupidus gigas, cum aeque se effectu vacuum animadverteret, feminam subornat, quae, cum obtenta virginis familiaritate eius aliquamdiu pedissequam egisset, hanc tandem a paternis procul penatibus, quaesita callidius digressione, seduxit; quam ipse mox irruens in artiora montanae crepidinis saepta devexit. 2 Opinantur alii, quod femineam mentitus effigiem, cum insidiosa arte protractionis domesticis puellam aedibus abduxisset, partes demum raptoris impleverit. |

A giant desired the same thing, but, finding himself equally foiled, he suborned a woman; and she, pretending friendship for the girl, served her for a while as her handmaid, and at last enticed her far from her father's house, by cunningly going out of the way; then the giant rushed upon her and bore her off into the closest fastnesses of a ledge on the mountain. Others think that he disguised himself as a woman, treacherously continued his devices so as to draw the girl away from her own house, and in the end carried her off. |

|

Dan 7.4.3 (p. 188,22) 1 Quod ut comperit Otharus, indagandae virginis gratia montis penita perscrutatus, inventam, oppresso gigante, secum abduxit. 2 Adeo autem gigantea sedulitas puellae caesariem nexili comarum astrictione revinxerat, ut pilorum perplexa congeries crispata quadam cohaerentia teneretur, nec facile praeter ferrum quis posset consertos crinium extricare complexus. 3 Denuo igitur variis rerum irritamentis aggressus puellarem in se provocare conspectum, cum diu torpentes nequicquam oculos attentasset, proposito parum ex sententia cedente, coeptum reliquit. 4 Sed neque puellam stupro violare sustinuit, ne splendido loco natam obscuro concubitus genere macularet. |

When Ottar heard of this, he

ransacked the recesses of the mountain in search of the

maiden, found her, slew the giant, and bore her off. But the

assiduous giant had bound back the locks of the maiden,

tightly twisting her hair in such a way that the matted mass

of tresses was held in a kind of curled bundle; nor was it

easy for anyone to unravel their plaited tangle, without

using the steel. Again, he tried with divers allurements to

provoke the maiden to look at him; and when he had long laid

vain siege to her listless eyes, he abandoned his quest,

since his purpose turned out so little to his liking. But he

could not bring himself to violate the girl, loth to defile

with ignoble intercourse one of illustrious birth. |

|

Dan 7.4.4 (p. 188,31) |

She then wandered long, and sped through divers desert and circuitous paths, and happened to come to the hut of a certain huge woman of the woods, who set her to the task of pasturing her goats. Again Ottar granted her his aid to set her free, and again he tried to move her, addressing her in this fashion: |

|

1 'Num meis mavis monitis adesse et pares votis sociare nexus quam gregi praesens olidisque curam ferre capellis? 2. Impiae dextram dominae refelle et trucem praeceps fugito magistram, ut rates mecum socias revisens libera degas! 3. Linque commissae studium bidentis, sperne caprinos agitare gressus, et tori consors refer apta nostris praemia votis! 4. O mihi tantis studiis petita, torpidos sursum radios reflecte, paululum motu facili pudicos erige vultus! 5. Ad lares hinc te statuam paternos, et piae laetam sociabo matri, si semel blandis agitata votis lumina pandas. |

1. "Wouldst thou rather hearken to my counsels, and embrace me even as I desire, than be here and tend the flock of rank goats? 2. "Spurn the hand of thy wicked mistress, and flee hastily from thy cruel taskmistress, that thou mayst go back with me to the ships of thy friends and live in freedom. 3. "Quit the care of the sheep entrusted to thee; scorn to drive the steps of the goats; share my bed, and fitly reward my prayers. 4. "O thou whom I have sought with such pains, turn again thy listless beams; for a little while — it is an easy gesture — lift thy modest face. 5. "I will take thee hence, and set thee by the house of thy father, and unite thee joyfully with thy loving mother, if but once thou wilt show me thine eyes stirred with soft desires. |

|

6. Quam tuli claustris toties gigantum, confer antique meritum labori et graves rerum miserata nisus parce rigori! |

6. "Thou, whom I have borne so oft from the prisons of the

giants, pay thou some due favour to my toil of old; pity my hard endeavours, and be stern no more. |

|

7. Quare etenim cerebrosa adeo dementire coepisti, ut

alienum ductare pecus et in monstrorum famulitio numerari

praeoptes quam pari consensus aptitudine mutuum tori

promovere contractum?' |

7. For why art thou become so distraught and brainsick, that thou wilt choose to tend the flock of another, and be counted among the servants of monsters, sooner than encourage our marriage- troth with fitting and equal consent?" |

|

Dan 7.4.6 (p. 189,22) |

But she, that she might not suffer the constancy of her chaste mind to falter by looking at the world without, restrained her gaze, keeping her lids immovably rigid. How modest, then, must we think, were the women of that age, when, under the strongest provocations of their lovers, they could not be brought to make the slightest motion of their eyes! So when Ottar found that even by the merits of his double service he could not stir the maiden's gaze towards him, he went back to the fleet, wearied out with shame and chagrin. |

|

Dan 7.4.7 (p. 189,28) |

Sigrid, in her old fashion, ran far away over the rocks, and chanced to stray in her wanderings to the abode of Ebb; where, ashamed of her nakedness and distress, she pretended to be a daughter of paupers. The mother of Ottar saw that this woman, though bestained and faded, and covered with a meagre cloak, was the scion of some noble stock; and took her, and with honourable courtesy kept her by her side in a distinguished seat. For the beauty of the maiden was a sign that betrayed her birth, and her telltale features echoed her lineage. Ottar saw her, and asked why she hid her face in her robe. Also, in order to test her mind more surely, he feigned that a woman was about to become his wife, and, as he went up into the bride- bed, gave Sigrid the torch to hold. The lights had almost burnt down, and she was hard put to it by the flame coming closer; but she showed such an example of endurance that she was seen to hold her hand motionless, and might have been thought to feel no annoyance from the heat. For the fire within mastered the fire without, and the glow of her longing soul deadened the burn of her scorched skin. At last Ottar bade her look to her hand. Then, modestly lifting her eyes, she turned her calm gaze upon him; and straightway, the pretended marriage being put away, went up unto the bride-bed to be his wife. |

|

Dan 7.4.8 (p. 190,7) |

Siwald afterwards seized Ottar, and thought that he ought to be hanged for defiling his daughter. But Sigrid at once explained how she had happened to be carried away, and not only brought Ottar back into the king's favour, but also induced her father himself to marry Ottar's sister. |

|

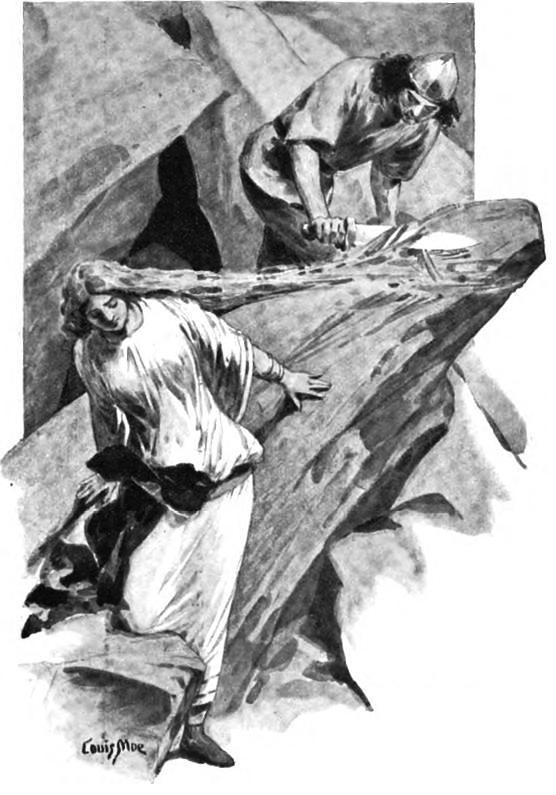

by Louis Moe

Viktor Rydberg

Investigations into Germanic Mythology Vol. I (1886)

100. SVIPDAG RESCUED FREYJA FROM

GIANTS’ HANDS.

SAXO ON OTHARUS AND SYRITHA. SVIPDAG IDENTICAL WITH OTHARUS.

When Menglöð requests Svipdag to name his family and his name, she does so because she wants jartegn (legal testimony; compare the expression með vitnum og jartegnum)[1] that he is the one whose wife she became by the norns’ decree (ef eg var þér kván of kveðin - str. 46),[2] and that her eyes had not deceived her. She also wishes to know something about his past life that can confirm that he is the same. When Svipdag had given as jartegn his own name and an epithet-name of his father, he makes only a brief statement in regard to his past, but to Menglöð it is an entirely sufficient proof of his identity with her chosen one. He says namely that the winds drove him on cold ways from his father's house to frosty regions of the world (str. 47). The word used by him, "drove" (reka), implies that he did not leave his home of his own volition, which we of course also learn in Gróugaldur: it is on his stepmother’s orders, and against his will that he departs to find Menglöðum, “those fond of ornaments.” His answer further demonstrates that after he had left his father's house he had made journeys in frost-cold regions of the world, such as Jötunheim and Niflheim, which was in fact regarded as a subterranean part of Jötunheim (see nos. 59, 63).

With languishing yearning, Menglöð has looked forward to the day when Svipdag would come. The mental state in which she finds herself when Svipdag sees her within the stronghold wall, sitting on "the delightful mound" surrounded by Asynjes and dises, is designated in the poem by the verb þruma, "to be sunk into a lethargic, dreamy condition."[3] When Fjölsviður comes and bids her "look at a stranger who may be Svipdag" (str. 43), she awakes in heated passion, and for a moment can scarcely contain herself. After she is persuaded that Fjölsviður's words and her own eyes have not deceived her, she at once seals the welcoming of the youth with a kiss. The words which the poem places on her lips testify, like her conduct, that it is not the first time she and Svipdag have seen one another, but that this meeting is a reunion, and that long before this, she knew that she had Svipdag's love. She speaks not only of her longing for him, but also of his longing and love for her (str. 48-50), and is happy that he has “again come to her halls” (að þú ert aftur kominn, mögur, til minna sala —str. 49). This "again" (aftur), which indicates a previous meeting between Menglöð and Svipdag, is found in all the manuscripts of Fjölsvinnsmál, and that it has not been added by any meter-polishing text-"improver" is demonstrated in that the meter would be improved if the word was not found there.

Meanwhile, it is absolutely clear from Fjölsvinnsmál that Svipdag never before had seen the stronghold within whose walls Menglöð ríki, eign og auðsölum (str. 7, 8).[4] He stands before its gate as an admiring newcomer, and poses question after question to Fjölsviður about the remarkable sights before his eyes. It follows that Menglöð did not have her halls within this stronghold, but dwelt in some other place, when, on a previous occasion, she had met Svipdag and became assured that he loved her.

In this other place she must have resided when Svipdag's stepmother commanded him to find Menglöðum, that is to say, Menglöð, but also someone else to whom the epithet "ornament-glad" might apply.[5] This is confirmed by the fact that this other person to whom Gróugaldur 3 refers is not mentioned at all in Fjölsvinnsmál. It is obvious that many events occurred and that Svipdag had many adventures between the episode described in Gróugaldur, when he had just received his stepmother’s order to find "those fond of ornaments," and the episode in Fjölsvinnsmál, when he again seeks Menglöð in Asgard itself.

Where could he have previously met her? Has there been a time when Freyja did not dwell in Asgard? Völuspá 25 answers this question, as we know, in the affirmative. An event once occurred, threatening to the gods and the existence of the world: the goddess of fertility and love had came into the giants’ power. Then all the high-holy powers assembled to discover "who had mixed the air with corruption and given Óður's maid to the giants’ race."[6] Of our Icelandic mythic sources, however, none mention how and by whom Freyja was liberated from the captivity of the powers of frost. Under the name Svipdag, our hero is mentioned there only in Gróugaldur and Fjölsvinnsmál; under the names Óður and Óttar one does not learn more there than that he was Freyja's lover and husband (Völuspá, Hyndluljóð); that he went far, far away; that Freyja then wept for him and that her tears became gold, and that she looked for him among unknown peoples and under many names: Mardöll, Hörn, Gefn, Sýr (Gylfaginning 35 [Pros. Edd. 114]). To get additional contributions to the myth about Svipdag we must turn to Saxo, where the name Svipdag should occur as Svipdagerus, Óttar as Otharus or Hotharus, and Óður as Otherus or Hotherus.[7]

There cannot be the least doubt that Saxo's Otharus is a figure borrowed from the divine myths and from the heroic sagas connected with them, since in the first eight books of his history not a single personality can be pointed to that does not have his origin there. But the mythic records that have come down to our time know only one Óttarr, and he is the same one who wins Freyja's heart. This alone makes it the duty of the mythologist to follow the pointer that is given here and see whether that which Saxo relates about his Otharus confirms his identity with Svipdag-Ottar.

The Danish king Syvaldus had, says Saxo, an extraordinarily beautiful daughter, Syritha,[8] who came into a giant’s power. This proceeded so that a woman who had a secret understanding with the giant succeeded in nestling herself in Syritha's confidence, in being adopted as her maidservant, and in enticing her to a place where the giant laid in wait. The latter hurried away with Syritha and concealed her in a wild mountain district. When Otharus learned this he started out in search of the kidnapped young maiden, ransacked the mountains’ recesses, found the one he sought and slew the giant. Syritha was in a strange condition when Otharus liberated her. The giant had twisted and pressed her locks together so that on the top of her head they formed, so to speak, one very hard substance which hardly could be disentangled without the assistance of an iron tool. Her eyes were indifferently staring, and she never lifted her gaze up toward her liberator. It was Otharus' decision to bring her back pure and virginal to her kinsmen. But the coldness and indifference she seemed to harbor for him was so difficult for him to bear, that he abandoned her along the way. While she now wandered alone through the wilderness she came to the abode of a giantess. The latter set her to watch her goats. Yet, Otharus must have regretted that he left Syritha on her own, because he sought and liberated her a second time. The mythic poem from which Saxo borrowed his story must have contained a song (reproduced by him in Latin paraphrases) in which Otharus explained his love to Syritha and bid her, whom he “with such severe toils sought and found," to give him a glance from her eyes as a token that she was willing to be brought back to her father and mother under his protection. But her eyes continually stared toward the ground, and in appearance she remained as cold and indifferent as before. Otharus left her then for the second time. From the context of the narrative it is clear that they were then not far from that border which separates Jötunheim from the other realms of the world. Otharus crossed the water, in the document probably the Elivogar rivers, on whose other side his father’s residence was situated. Of Syritha, Saxo again says reservedly and obscurely that "she in a manner that happened in antiquity hurried far away down over the rocks" —more pristino decursis late scopulis (Book VII, 227 [Hist. 333])[9] —an expression which allows us to suppose that in the mythic account she had hurried away bird-shape. However, fate brought her to the home of Otharus' parents. Here she represented herself to be a poor wanderer, born of parents who owned nothing. But her refined manners contradicted her statement, and Otharus’ mother received her as a noble guest. Otharus himself had already come home. She thought she could remain unknown to him by never raising the veil with which she covered her face. But Otharus well knew who she was. To find out whether she actually was as feelingless for him as it would seem on the surface, a pretend wedding was arranged between Otharus and a young maiden, whose name and position Saxo does not mention. When Otharus went to the bridal bed, Syritha, probably as the bridesmaid, was in his vicinity and lit him. The light or torch burned down, so that the flame came in contact with her hand, but she felt no pain, for there was in her heart a still more burning pain. When Otharus then told her that she should take care of her hand, she finally raised her gaze from the ground, and their eyes met. Thereby the enchantment resting on Syritha was broken: it was plain that they loved one another and the pretended wedding was changed into a real one between Syritha and Otharus. When her father learned this, he became taken with wrath; but after his daughter explained everything to him, his indignation was turned into favor and graciousness, and thereafter he himself married a sister of Otharus.

In regard to the person who enticed Syritha into the snare laid by the giant, Saxo is not entirely certain that it was a woman. Others think, he says, that it was a man in the shape of a woman.

It has long since attracted the attention of mythologists that in this narrative two names, Otharus and Syritha, occur which seem to refer to the myth of Freyja.[10] Otharus is undoubtedly a Latinization of Ottar, and, as is well known, the only one who had this name in the mythology is, as stated, Freyja's lover and husband. Syritha, on the other hand, may be a Latinization of Freyja's epithet Sýr, in which Saxo presumably believed he had found an abbreviated form of Syri (Siri, Sigrid). In Saxo's narrative Syritha is abducted by a giant (gigas), with the aid of an ally whom he had procured among Freyja's attendants. In the mythology Freyja is abducted by a giant, and, as is clear from Völuspa's words, likewise with the assistance of someone in Freyja’s vicinity acting as ally, for it is there said that the gods confer regarding whom it could have been who "gave," delivered, Freyja to the giant’s race (hver hefði ætt jötuns Óðs mey gefna). In Saxo, Otharus is of lower birth than Syritha. Saxo has not made him a son of a king, but compared to his bride a lowborn youth, whose courage to look up to Syritha, Saxo remarks, can only be explained by the great deeds he had performed or by his confidence in on his agreeable nature and his eloquence (sive gestarum rerum magnitudine sive comitatis et facundiæ fiducia accensus).[11] In the mythology Óður was of lower birth than Freyja: he did not by birth belong to the number of higher gods; and Svipdag had, as we know, never seen Asgard before he came there under the circumstances described in Fjölsvinnsmál. That the most beautiful and next to Frigg the foremost of goddesses, she who is the desire of all powers, the sister of the harvest god Frey, the daughter of the god of wealth, Njörd, she who with Odin shares the privilege of choosing heroes on the battlefield —that she does not become the wife of an Asa-god, but "is married to the man called Óður," would long since have been rated a fact both interesting and worthy of investigation by mythologists, if, in addition to speculations on the signification of the myths as symbols of nature or on their ethical meaning, one had cared to devote any research to their epic connection and causal relationships. Then one certainly would have come to the conclusion that this Óður in the mythic epic must have performed exploits which compensated for his lower birth, and thus one would have been exhorted to primarily direct the investigation to the question whether Freyja, who we know was in the power of the giants for some time, but was rescued from there, did not find her liberator in this very Óður, who afterwards became her husband, and whether Óður did not through this very act gain her love and become entitled to receive her hand. The adventure which Saxo relates incorporates itself into the actual work and fills a gap in that series of events which results from the analysis of Gróugaldur and Fjölsvinnsmál. It becomes comprehensible that the young Svipdag is alarmed, and regards the task imposed on him by the stepmother to find Menglöð far too great for his strength, if it is necessary to seek Menglöð in Jötunheim and convey her from there. It becomes comprehensible that on his arrival to Asgard he is so kindly received after he has fulfilled the formality of saying his name, if he arrives there not as the feared possessor of the Völund sword alone, but also as the one who restored the most loved and most beautiful Asynja to Asgard. One can then understand why the gate, which imprisons every uninvited guest, opens for him on its own accord so to speak, and why the savage wolf-hounds lick him. That his words: þaðan (from his father’s home) rákumk vindar kalda vegu,[12] are a sufficient answer for Menglöð to her question about his previous journeys becomes comprehensible, if Svipdag, like Ottar, has ransacked the frost-cold Jötunheim's eastern mountain districts in order to find Menglöð; and one can then understand why Menglöð in Fjölsvinnsmál can speak of her meeting with Svipdag at Asgard’s gate as a reunion although he had never been in Asgard before. And that Menglöð receives him as her already wedded husband, who now gets "to live together forever" with her (Fjölsvinnsmál 50), likewise receives its explanation by the improvised wedding Otharus celebrated with Syrithia before she returns to her father.

Otharus’ identity with the myths’ Óttarr-Óður-Svipdagur further is clear from the fact that Saxo gives him as father an Ebbo, which a comparative investigation shows to be identical with Svipdag's father Örvandil. To the name Ebbo and the person who bears it, I shall come further down (see nos. 108 and 109). Here it may be observed that if Otharus is the same as Svipdag, then his father Ebbo, like Svipdag's father, should appear in the history of the mythic patriarch Halfdan as his enemy (see nos. 24, 33). This is also the case. Saxo places Ebbo on the scene as an enemy of Halfdan Berggram (Book VII, p. 207 [Hist. 329, 330]). A woman, Groa, is the cause of the enmity between Halfdan and Örvandil. A woman, Sygrutha, is the cause of the enmity between Halfdan and Ebbo. In the one passage Halfdan robs Örvandil of his betrothed Groa; in the other passage Halfdan robs Ebbo of his bride Sygrutha. Saxo has, in a third passage in his History (Book III, p. 83 [p.138]), preserved the memory that Horvendillus (Örvandil) is slain by a rival, who takes his wife, there called Gerutha. Halfdan kills Ebbo. Thus it is clear that the same story is told about Svipdag's father Örvandil and about Otharus’ father Ebbo, and that Groa, Sygrutha, and Gerutha are variant names of the same dis of vegetation.

According to Saxo, Syritha's father was afterwards married to a sister of Otharus. In the mythology Freyja's father Njörd marries Skadi, who is Ottar-Svipdag’s foster-sister and systrunga[13] (see no. 108, nos. 113, 114, 115).

Freyja's byname Hörn (var. Horn) perhaps has its explanation in what Saxo tells of the giant's manner of treating her hair, which he pressed into one snarled, stiff, and hard mass. With the myth about Freyja's locks, we should compare the one about Sif's hair. The hair of both of these goddesses of fertility and fecundity is the object of violence by giant-hands, and it is likely that it is based on something symbolic of nature. Loki’s injury to Sif’s locks is made good through the skill and helpfulness of the primeval artists Sindri and Brokk (Skáldskaparmál 43 [Pr. Edd. I, 340]). In regard to Freyja's, the skill of a "dwarf" was probably required, since Saxo relates that an iron tool was necessary to separate and comb out the horn-hard braids. In Völuspá's list of primeval artists appears a smith with the name Hornbori, which possibly stands in connection with this.[14]

Reasons have already been given above (no. 35) that it was Gullveig-Heid who betrayed and delivered Freyja to the giants. When Saxo says that it was a woman who committed this treachery, but also points out the possibility that it was a man in the guise of a woman, then this too has its explanation in the myth, where Gullveig-Heid, like her accomplice Loki, is of androgynous nature. Loki becomes "pregnant by the evil woman" (kviðugur af konu illri).[15] In Fjölsvinnsmál 38, we again find the reborn Gullveig-Heid, under her name Aurboda, in Freyja's company, where she has ingratiated herself for a second time.

[1] Gulaþingslög 60: með skilríkum vitnum ok jartegnum, “with conclusive testimony and token,” cited in Cleasby/Vigfusson Dictionary s.v. jartegn, ‘a word’s token,’ which a messenger had to produce in proof that his word was true.

[2] ef eg var þér kván of kveðin, “if I was your wife by verdict”, cp. kviðr norna, “the verdict of the norns,” “fate.”

[3] In regard to a mental condition, Cleasby/Vigfusson defines þruma as “to mope, tarry, stay behind, loiter”; Egilsson as “become still and remain in one and the same place.”

[4] “holds power over the lands and costly halls,” [Björnsson tr.].

[5] The plural form menglöðum is found in all manuscripts of Gróugaldur 3, but is difficult to explain as it cannot be a plural form of the name Menglöð in the nominative [Menglaðir (masc.), Menglaðar (fem.), or Menglöð (neu.)], although menglöðum can be the dative of any of these. It could conceivably refer to Freyja and the meyjar who surround her (see Fjölsvinnsmál 37-38), or, as Rydberg thought, to Freyja and her brother Freyr.

[6] hverr hefði lopt allt / lævi blandit /eða ætt jötuns /Óðs mey gefna.

[7] [Rydberg’s footnote:] In Saxo, as in other sources of about the same time, aspirated names do not usually occur with aspiration. I have already referred to the examples Handuuanus Andvani, Helias Elias, Hersbernus Esbjörn, Hevindus Eyvindur, Horvendillus Örvandill, Hestia Estland, Holandia, Oland. (See no. #)

[8] In the English translations, Oliver Elton renders her name as Sigrid, and Peter Fisher as Siritha. Saxo however spells the name Syritha. See Saxonis Grammatici Gesta Danorvm herausgegeben von Alfred Holder, 1886, p. 225 ff.

[9] “in her old fashion, ran far away over the rocks,” [Elton tr.]; “had ranged far and wide as before over the rocky landscape,” [Fisher tr.]

[10] For example, Wilhelm Müller in “Siegfried und Freyr,” Zeitschrift für Deutsches Alterthum, 3rd. bd. (1843), pp. 43-53: “Syritha läfst sich mit Syr, beinamen der Freyja zusammenstellen”; and more recently Britt-Mari Näsström, Freyja—the Great Goddess of the North. (1995), p. 157: “Victor Rydberg suggested that Siritha is Freyja herself and that Ottar is identical with [the] same as Svipdagr, who appears as Menglöd’s beloved in Fjölsvinnsmál. Rydberg’s intentions in his investigations of Germanic mythology were to co-ordinate the myths and mythical fragments into coherent short stories. Not for a moment did he hesitate to make subjective interpretations of the episodes, based more on his imagination and poetical skills than on facts. His explication of the Siritha-episode is an example of his approach, and yet he probably was right when he identified Siritha with Freyja.”

[11] “kindled with confidence in the greatness either of his own achievements, or of his courtesy and eloquent address,” [Elton tr.]; “fired perhaps by his great achievements, or perhaps sure of his charm and eloquence,” [Fisher tr.]

[12] Fjölsvinsmál 47: “thence was I driven by winds on cold ways.”

[13] Cleasby/Vigfusson Dictionary, sv. .systrunga: “one’s mother’s sister’s daughter, a female cousin.” i.e. first cousin on the mother’s side.

[14] Völuspá 13: Codex Regius, Hornbori; Hauksbók, Fornbogi.

[15] Hyndluljóð 41.

HOME