| 1643 The Discovery of the Poetic Edda by Guðbrandur Vigfússon in Corpus Poeticum Boreale (1883) How the Codex Regius Manuscript came to be called the Elder or Poetic Edda [HOME] |

||

§ 1. The Decadence of Old Learning |

||

It has been long taken for granted that Iceland is and has been a land of antiquaries, a place where the old traditions, nay more, the old poems and myths of the Teutons have lingered on unbroken; and glowing phrases have painted its people as a Don Quixote of nations ever dreaming over the glorious reminiscences of the gods and heroes. It is to the credit of the Icelanders as a living people that it is not so. Yet such, if he had formulated his creed, would have been the Editor's belief before he began to look for himself, some twenty years ago, into the state of literature and literary tradition in the middle ages and the post-reformation days of Iceland. In the Árna-Magnæan Collection, a vast congeries of all kinds of documents bearing on the subject, memoranda, letters, vellums, fragments of vellums, and paper-copies of vellums, there exists ample material for getting at some notion of the true state of the case. It was while working at this collection, making careful statistics of these vellums and the vellum fragments representing lost vellums, that the opinions now set forth forced themselves bit by bit upon the Editor. The following results came out from a minute enquiry into the state of the MSS. of the classical literature—the Sagas touching Iceland, the Kings' Lives, the Older Bishops' Lives, etc. After the fall of the Commonwealth, in 1281, throughout the next ensuing century, there was a great activity for collecting and copying the historical literature of the past. By far the greater portion of the Sagas have gone down in fourteenth-century MSS., some of which are in fact great collections of Sagas. This contained the great collections such as Sturlunga A and B, Hulda, AM. 6t, Flateyjarbók, Waterhorn-book, Berg's-book, which all belong to this epoch, as do also Codex Wormianus, the Stjórn vellums, Hauksbók. It was in fact an age in which a marked amount of curiosity was taken by the survivors of the old families as to the history of the past. The great vellums speak, though no other records are left, for this was an unproductive though appreciative age. But that the public taste was far otherwise set during the next hundred years is proved by the rapid fall in the number of copies of classic works. Thus, as regards the number of vellums, the fifteenth century stands to the fourteenth in a ratio of 1 to 3 or even 4. Not that writing or copying had ceased, there are still many vellums, but they contain Sagas on subjects taken mostly from foreign or fictitious romances, or Skrök-Sögur [pseudo-Sagas] or Saints' Lives or the like. The end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth are mainly marked by ' Rimur,' and poems on saints in a cloister style, with a stray true Saga vellum now and then. At last we reach a period (1530-1630) of which hardly any Saga MSS. exist: no single copy taken of Landnama, or Edda, or Sturlunga, or Laxdæla, one transcript of Njals Saga perhaps, and some stray antiquarian scraps. In fact, after careful examination, we cannot point to any classic which had kept its place in popular favour or popular remembrance. For instance, has a fifteenth-century Rimur-maker to give a list of luckless lovers or gallant and unfortunate heroes (a favourite topic which at once set forth the wide knowledge of the poet and whetted the hearer's hunger for another song), what does he do? Of course he turns to the woe of Gudrun, the proud sorrow of Brunhild, the devotion of Sigrun and Cara, the gallantry of Helgi! Not at all, he never mentions their names. Then he speaks of Njal and Gunnar, Egil, of Skarphedin, Kjartan, of Gretti! Not a whit more. The only Icelanders whom he remembers are Poet-Helgi and Gunlaug Snake's-tongue. But he grieves for the grief of Tristram and Isolt, of Alexander and Helen, of Hector and Iwain, of Gawain and Roland, and of the heroes of a score of imaginary stories. Our friend Dr. Kölbing, who has collected passages[1] where such lists occur in his Beytrage (Breslau 1876), has been kind enough to send us a copy of the unpublished Kappa-kvaedi, composed by a West Icelander c. 1500, from which we have extracted the following typical list: Hector, David, Mirmant, KarlaMagnús, Otwel, Balan, Rolland, Walter, Baering, Errek, Ivent, Floris, Gibbon, Philpo, Tristram, Partalopi, Remund, Konrad, Asmund, Mafus (Maugis), Clares, Alanus, Florens, Belus, Landres, Herman, Jarlman, Victor and Blaus, Anund and Randwe, Saulus, Anchises, Ahel, Helgi, Hogni, Hialmar, Arrow-Odd, Anganty, lllugi, An, Thori Highleg, Vilmund, Solli, Hagbard, SkaldHelgi, Finnbogi, Thorstan Bayar-magn, Einar, Elling, Bui Digri, Vagn, Ref, Oddgeir, the two Ólafs, Harald, Ring, Ulf the Red. Of all Islendinga Sagas, Njal's Saga has been most copied: counting every strip of vellum which once formed part of a manuscript, we shall find out of some fifteen MSS., one of the thirteenth century, ten of the fourteenth, three of the fifteenth, and one of the sixteenth. This Saga was perhaps never utterly forgotten, though of a certain but little read. More statistics on this head are given in Prolegomena, where the history of the literature is more fully treated than suits our present purpose. The facts are however clear enough, that the taste of the times had completely changed by the year 1500, that there was neither interest in nor remembrance of the old life and old literature. This ignorance even went so far that the very constitution of the Commonwealth was forgotten, and it was the law of St. Ólaf, not the law of Skafti or Wolfljot (whose names were clean perished from the popular mind), which had now become the ideal of the Icelandic patriot. The English trade and the change of physical circumstances may have something to do with this rapid but complete oblivion of things past, this absolute neglect of history and tradition. To the Icelander of the sixteenth century, even the fifteenth century was a mythical, semi-fabulous age; Lady Olof, Björn her husband (d. 1467), the feuds with the English traders, were as legendary to them as Njal had once been to the twelfth-century Icelander. The pedigrees go no higher up. The Saga tide is not even seen looming behind. The legend of Sæmund Frodi as Virgilius, is the work of the Renaissance, grown from the story in Bishop Jón's Saga. The difference between new and old was still more marked by the Reformation, which cut the last link that bound Iceland to the past—the Old Church. The change which about the same time affected the tongue itself is but an outward token of a deep and real phenomenon. And now the tide begins to turn. About the last ten years of the sixteenth century we notice symptoms of a Renaissance, the impulse for which came from abroad. There are only two marks of native interest in these matters, one provoked by the re-discovery of Landnamabok, the other by the knowledge of the single vellum of Hungrvaka. The influence of the former is shown in the pedigrees compiled by Odd, Bishop of Skalholt 1589-1630, in his earlier years, which form the nucleus for our information respecting the families of the last Catholic and first Protestant bishops.[2] The latter is manifested by the Lives of Bishops, drawn up by Jón Egilson, at the instance of Bishop Odd, who also took down the life of the last Roman Catholic bishop from his living grandson, in imitation of the venerable model which had preserved the biographies of their Hungrvaka predecessors. The Lives in Hungrvaka were to Bishop Odd and Jón Egilsson what Suetonius was to Einhard. Still, though here and there, there may have been a possibility of a revival, the real motive power was actively supplied from abroad. About 1550 there was found at Bergen a MS. vellum of the Kings' Lives, all the great MSS. of which were in Norway. A Norwegian began to translate the Lives. They were published at Copenhagen in 1594, and being Lives of Kings, Royal interest was roused in the matter in Denmark, which led to the employment of Icelanders, who were better able to interpret documents the language of which they still spoke with little change. [1] Compare the list of heroes from Skida-rima, ii. p. 396; and the following from Hjalmtheow's Rimur (fifteenth century)—Arthur and Elida, Tristram and Ysolt, Hogni and Hedin, Philotemia, Ring and Tryggwi, Iwain, Alexander and Elene, David and Absalom; from Gerard's Rimur (fifteenth century)—Priamus, Mirman, Iwain, Flores and Blanchefleur, Samson and Dalila, Sorli, Earl Roland; from Heming's Rimur (fifteenth century)—Godwine, Sörli, Parthenope, Raven and Gunlaug, Poet-Helgi, Tristram and Isolt. For Gunnar and Hallgcrd, or Gudrun and Kiartan, we look in vain. |

||

| § 2. The Revival—Ármgrím The Learned, etc. | ||

The first two Icelanders who are drawn into the study of their own old literature are Árngrím the Learned [Arngrímur lærði (1568-1548)] and Björn of Skardsa [Björn á Skarðsá (1574-1655)] their activity would extend from 1593 to 1643. To understand the character of the revival, of which they were the pioneers, we must put ourselves as far as possible back into their position, for till we have done so, it will be impossible to understand their views or interpret their statements.

Árngrím Jónsson[1] was born in 1568. He was fostered by Gudbrand, the pious printer-bishop, whose life-long friend and right-hand man he grew up to be. He was priest of Mel and official is or co-adjutor of the Bishop for his diocese of Holar; hence his time was passed between his cure and the Bishop's seat. He wrote four works: the Brevis Commentarius Islandiae, 1593, on the History of Iceland; the Supplementum, 1596 (which only exists in MS.), on the Lives of Kings; the Crymogsea, 1609, a Constitutional History of Iceland; and Specimen Islandise, mostly drawn from Landnama, printed 1643, written C. 1635. He was a correspondent of Ole Worm, the Danish scholar, survived his foster-father for many years, and died in 1648.[2] Ármgrím, from his influential position and from authority conferred upon by the King, had the best possible means of getting at what MSS. and remains were within reach, and he availed himself of his opportunities, so that, as he tells us, he had no less than twenty-six vellums in his care at one time.[3] It is therefore highly interesting for us to trace through his books what books he does not know at the different stages of his literary life. He never knew Sturlunga Saga, Islendinga-book, Bishop Ami's Saga, Flateyjarbók,[4] all most important works for his peculiar study, the constitutional antiquities of his country. Snorri he only knows as 'auctor Eddæ,' i.e. of the Gradus. Ari, as the great historian of the beginning, and Sturla as the chronicler of the later days of the Commonwealth, are wholly unknown to him. The older (Eddic) poems, of course, he was totally ignorant of. We must bear in mind the range of his authorities to judge his work fairly: considering the imperfection of the sources he had to work with, his books show high sagacity and good sense.

Björn Jónson of Skardsa was born in North Iceland 1575, and died blind at a high age in 1656. He betook himself to the study of antiquities when about fifty years old. Though a franklin and farmer, self-educated (he had never been to the High School, or learned Latin), he had a poetic imaginative turn of mind, and also, it appears, a force of character and enthusiasm, which led his dicta to be eagerly accepted by his contemporaries, as we shall find by and by. His style is euphemistic, and he coined many words. Of the same generation is Magnús Ólafsson, priest of Laufas (15741636), well known as the author of a compilation or rearrangement of the Codex Wormianus of Snorri's Edda, in which the Gylfaginning is turned into sixty-eight Dæmisögur (short Tales, like the brief apologues of Eastern story-books), and the Gradus-part into an alphabetical index. His book has superseded the original in popular knowledge and esteem; and it was through hearing it read aloud by his old friend, Jacob Samsonson [ii. p. 412, No. 8], that the Editor when a child first got to know the story of Balder. [1] He was the first Icelander who took a family name, calling himself Widalin, from his native place Wididale. All Icelandic Widalins, a goodly race of men, are descended from him. Yet he himself mostly goes by the name Ármgrím, and so we designate him. |

||

| § 3. Bishop Brynjólf, etc. | ||

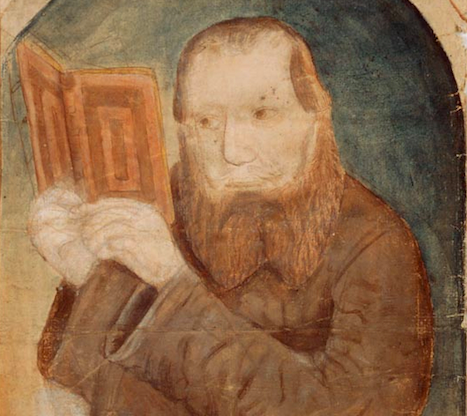

The name of Bishop Brynjólf of Skalholt (born Sept. 14, 1605, bishop 1639-1675) will be forever connected with the old revival of letters, with the Edda MSS., and other treasures which his care preserved for us. But this Icelandic Parker is a man whose personality was a striking one, and he was a little king in the island in his own day, looked up to and reverenced for his learning, his rank, and his force of character. He is brought vividly before the eye—big, tall, stern of face, with red hair close-cropped to the ears, and long flowing red beard, speaking with decision, and nodding his head as he spoke; a man of proud feelings, dwelling with satisfaction upon his descent from Bishop Jón Arason, his mother's great-grandfather, and perhaps for that very reason void of the intolerance which was commonly felt at that time towards the old Church. He would neither speak ill of her himself, nor suffer others to show irreverence towards her ceremonies or hallowed images, saying that such things were well fitted to waken feelings of religion within a man, and loving to pray with his eyes upon a crucifix. A shrewd saying of his on the Reformation is worth record: "The Church had a scabbed head, but Luther took a currycomb to it, and scraped off hair and scalp and all."

He was a great observer of times and seasons (like Laud), refusing to start on a journey on a Saturday, and recording and prognosticating from coincidences, carefully keeping the birth-hour of his children and friends that their nativity might be accurately drawn, and regarding himself as possessing a certain prophetic gift. His learning was renowned as marvellous by his contemporaries, and remembered by tradition; but, save a few letters and annotations, it has gone; and the man who could talk Greek with a Greek, and keep up a correspondence with the learned world of the continent from his far-off see, has left but what he would have regarded as the fragments of his library as his enduring literary monument. Several good anecdotes touching him are given by Jón Halldorsson (1665-1736), priest and dean of Hitardale, in his Biscopa Ævi (Lives of Bishops), a book of worth, with some pleasant biographic detail in it, which ought not to remain longer unprinted, for it contains the best historic material for the times of which it treats.[1] "I saw Brynjólf once," says Jón; "I was then nine years old" [1674]: and he tells how he and other boys were outside the tent at the Althing [moot] one evening, holding the horses for their fathers and masters, like Shakespeare's 'boys,' and no doubt chatting and laughing among themselves, on the north side of the church at Thingvalla, as their elders were within, for the Bishop was taking leave of the priests and franklins, and the parting cup was going round. "It was then that Master Brynjólf came out alone among us, somewhat suddenly. He was rather merry (gladr), and he asked the first of us, as he greeted him, about his family and his name and his forefathers, till he could get no further answer out of him; and he bade the boy to look him straight in the face while he spoke to him; and in the same way he questioned one after the other, and last of all me, Jón Halldorson, for I was the youngest. And to all of them he said something kind as he turned from them, but he patted my head and said, 'Age is upon me, and youth is upon thee';[2] thou art very young, and I am grown too old for thee to get any good from me.' Then he turned back again into the tent." He was unlike other men in many small ways; one notes his characteristic monogram Brynjólf had two children, and their fate has a real bearing on the literary history of the Eddas and Sagas, for had they not predeceased him, the books and MSS. which he had collected would hardly have been scattered and destroyed as they were. His son Halldor (born 1642), the younger of the two, was not successful at the High School, and was accordingly removed by his father and sent to England to try his luck there,—for there was some trading, smuggling, and fishing still carried on between the two countries. Here however he fell ill and wished to start for home, but the Dutch war was going on, and there was a fair chance of an English ship being captured just at that time, when the Dutch were masters of the North Sea; so he died and was buried at Yarmouth, Oct. 1666. His father, when he heard the news, sent over an epitaph to be set on his grave:— "Hallthoris Yslandi cineres humus Anglica senia, It would be good to know whether it was duly inscribed, and whether the poor boy's tomb is still to be recognised. Sad as was this loss, the blow he had suffered four years before was far crueller and harder to be borne. His daughter Ragnheid (born Sept. 8, 1641) was the very apple of his eye, a beautiful and accomplished girl, the maiden to whom Hallgrim the Poet sent, in May 1661, one of the three autographs of his Passion-Hymns, then fresh from his hand. The Bishop had taken into his household one Daði, a parson's son, a clever, handsome, merry young fellow, a fine penman and good at all bodily feats, but a man of no worth as it turned out. He was brought into contact with the Bishop's daughter, to whom he acted as tutor, and being entirely unscrupulous he took advantage of his position to ruin the poor girl. He was clever enough to get out of the way before the Bishop should learn the news, and direct vengeance never fell on him. The Bishop was almost distraught at the disgrace that had fallen upon his daughter, and the very love he bore her served but to make the wound bite deeper. He was heard to repeat the words of Psammenitos,[4], and it would seem that he never got over the melancholy which this catastrophe brought into his life. He obtained the king's Letters of Rehabilitation for Ragnheid (as is the use in Lutheran countries), but she did not long survive her trouble and the terror which her father's rage and grief had caused her, but sank and died in Lent 1663, in her twenty-second year.[5] Her son was adopted by the Bishop, but he too died young (1673), so that there is no direct descendant of him who in his lifetime was held the highest and sorest tried of any man in Iceland. It was during the very year of this domestic tragedy, 1662, that Thormod Torfaeus was in Iceland hunting after vellums for the king's new-founded library, and it is highly probable that the MSS. he took back to Denmark with him as a gift from Bishop Brynjólf to the King's Library [see Prolegomena, pp. 145, 146] were intended as a conciliatory present by which the royal favour he demanded might be the more readily taken into consideration, and so, along with other treasures, Edda, Codex Regius, left Iceland for good. The Bishop felt that he had no more need now for the books, we may fancy; his interest for the time at least must have gone, for a collector does not send away so many of his choicest treasures (some of them he had had twenty years) without good reason. "When the end came, Brynjólf prophesied the place and manner of his death 'alone in the room,' and appointed his grave outside the cathedral church at Skalholt apart from all the other bishops. But his heirs collateral,[6] who cared so little for his memory as not even to have marked his grave, treated his books with scant reverence, and the Icelandic vellums, many of them, had disappeared before Árni Magnússon, thirty years later, came to rescue all that was left of vellum MSS. in the Island. Some of the Latin printed books may still be lingering on in Iceland, mouldering away, as the Editor saw one folio with his monogram twenty-four years ago. Most lucky it was that Brynjólf not only sent some of his best MSS. to Denmark, where all save one (Gisli's Saga) have safely reached us, but had taken care to have copies made of them by Jón Erlendsson, for these transcripts, being easy to read, were preserved by those into whose hands they fell, while the original vellums were left to positive ill-use or carelessness, which soon destroyed many of them. For instance, Libellus and Landnama, both old vellums once in the Bishop's library, were copied by Jón Erlendsson in 1651, and somehow perished in the thirty years' interval between the Bishop's death and Árni's arrival.

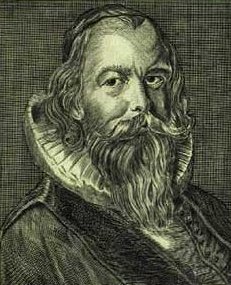

We have quoted from the correspondence of Brynjólf and the Danish scholar Ole Worm; a word or two upon the latter will not be out of place. Born 1588, he seems to have taken early to study, and as he was a man of good position and of great thirst for knowledge of every kind, he came into relations with most of the scholars within reach of his busy pen. His correspondence with his Icelandic contemporaries has been published. He was connected with the publication of Peter Clausen's translation of Heimskringla. Worm fell into the study of Runes, which he treated in his peculiar mystic way, and in his well-known Literatura Runica he makes mention of, and cites, the Poetic Edda. Ármgrím sent him out the MS. of Snorri's Edda, which has ever since borne his name, Cod. Wormianus, as Ármgrím says 1629: "The Edda and the Skalda that is affixed to it, as it is my manuscript, I grant freely to Master Worm for as long as he will." Worm also acquired other MSS. which did not pass into the University Library, but finally became Árni Magnússon's property. Stephanius, Worm's contemporary, born 1599 and schooled at Herlufsholm, was a great correspondent of Bishop Brynjólf, and really a fine scholar; his edition of Saxo is the first piece of true editing of a Northern classic, and shows at every page wide reading and sound criticism of a shrewd Bentleian quality. The Notæ Uberiores, which appeared in 1644, but which had necessarily taken some time to pass through the press, frequently refer to the help he received from Icelandic scholars. Stephanius became possessed of several Icelandic MSS., which (in 1651) were sold by his widow to the noble collector De la Gardie, whence they passed to the Upsala Library in 1685 (along with Codex Argenteus); the best of them is the Codex Upsalensis of Snorri's Edda. [1] The Editor, when a boy of fourteen, remembers listening to portions of it read from MSS. as evening entertainment. |

||

| §

4. The History of the Word 'Edda.' a. Before A.D. 1642. |

||

The word 'Edda' is never found at all in any of the dialects of the Old Northern tongue, nor indeed in any other tongue known to us. The first time it is met with is in the Lay of Righ (Rígsþula), where it is used as a title for great-grandmother, and from this poem the word is cited (with other terms from the same source) in the collection at the end of Skáldskaparmál. How or why Snorri's book on the Poetic Art came to be called 'Edda' we have no actual testimony (the Editor's opinion thereon is given at length in Excursus IV to vol. ii), but in the vellums of it which survive the following colophons are found; viz. in Codex Upsalensis:— "This Book is called Edda, which Snorri Sturlason put together according to the order set down here:—First, concerning the Æsir and Gylfi. Next after, Skáldskaparmál and the names of many things. Last, the Tale of Metres which Snorri wrought for King Hakon and Duke Skuli.”[1] And in the fragment AM. 757: "The book that is called Edda tells how the man called Ægir," etc.[2] Snorri's work, especially the second part of it, Skáldskaparmál, handed down in copies and abridgments through the Middle Ages, was looked on as setting the standard and ideal of poetry. It seems to have kept up indeed the very remembrance of court-poetry, the memory of which, but for it, would otherwise have perished. But though the mediæval poets do not copy ' Edda' [i. e. Snorri's rules], they constantly allude to it, and we have an unbroken series of phrases from 1340 to 1640 in which 'Edda' is used as a synonym for the technical laws of the court-metre (a use, it may be observed, entirely contrary to that of our own days). Thus beginning with Sacred Poems between 1340-1400, Eystein says in Lilia, verse 97: "In all speech the substance is the thing, though the obscure rules of Edda may here and there have to give way; so I shall write plainly at all events."[3] Again, Abbot Ami (c. 1380): "The great masters of the Eddic Art, who cherish the precepts of learned books, may think this poem too plain, but the plain words of Scripture are better suited in my opinion to the lives of saints, than the dark likenings which give neither strength nor pleasure to anyone.” And Abbot Ármgrím (1345): "I have not told my tale according to the rules of Edda, so my verses are not smooth to the tongue. I give you but poetastry. I am far from the good poets." And in Nicholas Drapa, Hall the priest (c. 1400) says: "I am not equal to my subject, I lack wisdom, gentle breeding, etc., eloquence, the study of good poets, the knowledge of Edda's noble Iaws.” From 1450-1550 we have numerous examples from the Rimur. "I have never heard or seen Edda," i. e. I have never learnt poet-craft. "Poets would do better not to be everlastingly fumbling over the Edda similes;" "There is no pleasure in speaking in riddles, according to the dark rules of Edda;" "I am tired of Edda;" "I send my poem forth though I have not learnt my words or art from Edda!"; "I have never learnt any of Edda's figures!"; "No help of Edda have I got, she is thought hard to master, and she has never got into my brains!" Again, after 1550: "The crooks or gambits of Edda;" "I have no help from Edda;" "Many sing though they know little of Edda;" "I shall not fix my mind on Edda, the meaning is the important thing;" "Edda is said to be a glorious book by those who study her;" "The laws of the poets and the rules of Edda;" "The similes or figures of Edda;" and so on down to the times of Ármgrím, and Magnús, and Björn of Skardsa.[4] It is their theories and beliefs respecting such ancient literature as they knew, and particularly the works of Snorri, that we must next consider. It must be borne in mind that Codex Wormianus was the MS. of Snorri's work, which they knew; that it contains besides 'Edda' a number of additional treatises (a book on the grammatical figures by Ólaf, and the alphabetic studies of Thorodd and his follower) which were known as 'Skalda.' The first occurrence of this latter word is in the Rimur of Valdimar, by a poet of the end of the sixteenth century [see at the end of Introduction], an allusion, we doubt not, to Codex Wormianus itself. Now Codex Wormianus does not contain the ascription to Snorri, and there is no evidence that the name of Snorri was traditionally connected with the ' Edda,' of which the Rimur-makers speak so often. For, though we have so many references to Edda's rule, we have none to the rule-maker, a thing most strange, but which may fairly be taken as evidence that Snorri was clean forgotten in the popular mind at any rate. The first person who gives Snorri as author of the Edda is Ármgrím in Crymogæa, 1609, most probably on the authority of some copy or fragment. It is not impossible of course that he may have heard of or had a glimpse at (the present) Codex Upsalensis of Edda, which, as we have seen, contains the ascription. Björn of Skardsa, on the contrary, had evidently never heard of Snorri as connected with the Edda, and had already formed his own theory on the "authorship of the two great sections (Edda and Skalda) of the Codex Wormianus. One he ascribes to Sæmund the Historian, one to Gunlaug the Benedictine Monk. But how in the world came he to place Sæmund and Gunlaug together f In this way we think. He only knew of one book that had come down from the old days in which there was mention of authors' names, Bishop Jón's Life. This Life contains the statement that it was written by Gunlaug the monk, and it also contains a reference to a more distinguished Icelandic scholar, Sæmund, of whom it relates the very interesting legend which pictures him as a disciple of the black art and a prodigy of learning. Björn's flighty fancy is fired, in one hand he holds the two anonymous works, in the other two authors, and so he boldly pairs them off, as in a game of cards, giving Edda to Sæmund, Skalda to Gunlaug. For is not Edda worthy of Sæmund? And does not Skalda suit Gunlaug, who knew all about Sæmund and was a learned man in his day too? With this satisfactory and pleasing hypothesis he rested in high content till he found that Ármgrím confidently named Snorri in his list of Speakers as 'auctor Eddæ.' He will not surrender his pet theory, and he will not dispute Ármgrím's statement, so he coins an hypothesis of reconciliation, and holds that the Edda was begun by Sæmund and completed by Snorri; but he leaves Gunlaug as author of Skalda, which he remained till late in last century.[5] In this final form we get it expressed in his Gronlandia [AM. 115, 8vo, autogr.], when, having spoken of the Skalda treatises as "written by Monk Gunlaug, who lived under Waldimar the Second" (!), he proceeds: "he forbids one to draw the synonyms and likenings farther than Snorri permits [quoting from Ólaf’s treatise]; that must have been Snorri Sturlason the Lawman, he lived in the days of Gunlaug; Snorri gathered the synonyms and many kinds of names and added them to Edda, which Priest Sæmund the Wise had compiled aforetime." This theory Ármgrím accepts and upholds as a tradition inhis correspondence with Ole Worm, 1636, who is a little puzzled by his loose statements. "Why do you speak of Edda as Sæmund's, when you in Crymogaea called Snorri its author?" Ármgrím answers, 1637: "I can solve your difficulty; in our records these words are plainly to be read, 'Snorri Sturlason lived in the days of Gunlaug the monk, he added to the Edda which Sæmund the historian had composed." A striking statement! What are these 'records?' Nothing but the words of Björn given above, written only ten years back, quoted almost letter for letter. Ármgrím is anxious to be thought consistent, and we are afraid the 'monumenta' looks a little like an equivocation. Certainly two years later Ármgrím is bolder, when he writes to the same correspondent: "Hence it is that Edda is found in old records ascribed both to Sæmund and Snorri, the plan and beginning being Sæmund's, the additions and conclusion Snorri's'." To show (in addition to these words of Ármgrím), (1) that Björn habitually spoke of the 'Edda' as Sæmund's or Snorri's, (a) that by this 'Edda' is always meant the prose Edda, (3) that he used the name of Sæmund wherever he wished to find an author for a great classic—the following extracts will be of use. In a Commentary on Law-phrases Björn quotes Skáldskaparmál three times as Sæmund's alone, once as Snorri's and Sæmund's, and the Thulor once as Sæmund's, twice as Snorri's, sometimes citing word for word, so that there can be no mistake; e. g. "Sæmund the historian says flatly that 'the speech of these peoples is called the Danish tongue;'" and "Sæmund the historian says, 'next to the liege men or barons came they who are called holds.'" Which passages are to be found in Edda Sksk. ch. 53'. He also cites from Skalda as Gunlaug's. To Sæmund he ascribes 'Njal's Saga and the great Saga of Ólaf Tryggvason' in his notes to Landnama-bok. Very interesting is the quotation given by Árni Magnúson (1696) from Björn, Commentary on Gest's Riddles, which we now take to be lost, written in 1641 (observe the date):—" The prose Edda, which we commonly call Snorri's Edda, Björn of Skardsa attributes to Sæmund'." Árni Magnúson (1696) has also preserved the statement:—" M. Thormod Torfisson (now 60) says, that in his youth he had heard his father quote somewhat from Sæmund's Edda, which he said he had himself read in the book some time ago." A notice easily interpreted in the light which we are now able to throw upon the invariable use of the words Sæmund's Edda for the 'Prose Edda' before 1642. We may now leave Björn in 1641 with his theory on the one prose Edda with two authors known to him, and turn to Magnús Ólafsson, who first conceived the idea of a second Edda having existed. He was not content with speculating on the authorship of the Edda, but boldly goes to the root of the matter, and holds that Edda, as preserved in Codex Wormianus, is merely a compendium of an archetypal Edda, a gigantic cyclopædia of ancient lore, composed by the Æsir themselves, at least their grandsons. As he says: "From the poems of the ancients [the fragments of poetry in Snorri's Edda], and also from certain titles of the Æsir, and especially Woden, and indeed of other things also, it appeareth that there hath been another older Edda, or book of stories, put together by the Æsir themselves or their grandsons, which hath perished, and of which our Edda is, as it were, an epitome; for of very few of these many names, which are applied to Woden on account of divers adventures of his, as Edda itself declareth, can any account be given from the stories contained therein, yea, nor even of the names of many others, which are therein to be found." The theory is grandiose, and not wholly fanciful. Snorri's Edda stands to tradition in much the same relation which Magnús dreamed that it stood to his Arch-Edda; and those names, in the Thulor, of sea-kings and ogresses, which we cannot identify, are indeed evidences of lost legends and faded myths. Bishop Brynjólf accepts the theory, but he has heard of Björn's ideas on the authorship of Edda, and he effects a decent episcopal substitution of Sæmund for the 'Æsir or their grandsons.' In a letter to Stephanius (1641) he expresses himself with a certain fervour: " Where be those mighty treasuries of all human knowledge, written down by Sæmund the Wise, and in especial that most noble Edda, of which, beside the name, we have now left scarce a thousandth part; yea, and that which we have, had been altogether destroyed had not the compendium of Snorri Sturlason, which we have, preserved to us what I would call the bare shadow and foot-print of that ancient Edda, rather than the work itself? Where too is that huge volume of histories, from Woden down to his own day, which Ári, surnamed the Historian, compiled? [Alluding to another theory of the author guessing Björn.] Where be those most excellent writings of Monk Gunlaug? Where be the royal poets' songs that were held as marvels over the whole northern worlds?" The last stage of the Magnús theory is reached by the poet Peter Thordsson, who says (c. 1650): "The story goes, that in the old days in Gautland, there was a king's daughter named Edda, who was held the greatest paragon for wise counsel and for her many accomplishments, but above all for knowledge and book-learning, of any maid or matron that was living in her day. She flourished a short time after Woden and the Æsir came hither out of Asia to the lands of the North and took them under their rule. And because of her wisdom she wrote down in a continuous story the dealings between Woden and King Gylfi of Sweden, who was named Gangler, etc. . . . But I have never found that these histories have ever been put down in writing since Edda wrote the 'Beguiling of Gylfi' (Gylfaginning) till Snorri Sturlason wrote his Edda.” In Stockholm there is an interesting MS. (Holm. Isl. 38, fol.) containing an Essay on Edda composed in 1641, a date to be noted. This essay is an omnium gatherum of all kinds, and, amongst other things, contains the first written information respecting the elves and other popular legend-matter, for which the Editor (in 1861) made use of it in his preface to Mr. Árnason's Icelandic Fairy-tales. The author's name is not given, but his personality is clearly pointed out, for instance, in the following passage :—" This book, like all my other things, I lost in 1616, whereof it is no profit to think." Which is an allusion to the persecution that Jón Lærdi underwent for siding with some Gascon pirates in the west of Iceland in 1616, and for being suspected of sorcery, as he tells us in his autobiographical poem, called ‘Fjolmod’ (the Curlew). Jón draws his information from the few books which he knew—Snorri's Edda and its two arrangements (Laufas Edda and Upsalensis Edda) and Hauksbók; and he quotes no poetry but what is found in these, save two verses from Völuspá, which do not occur in the prose Edda, but are found in Hauksbók (his favourite store-house), as we can tell by the reading he follows. He also tells the story of Giant Thrym, but here again from the Rimur Thrymlor, not from any other source. Now Thrymlor is contained in the big Rimur vellum which was found in the west of Iceland, precisely the spot from whence Jón Lærdi came. Jón accepted Magnús' grand theory, with the same modifications as Brynjólf had supplied, as we see from such passages as: "Then the clerk Snorri Sturlason of Reykholt, the lawman of the south of the country in the days of Gudmund Arason the bishop, the fifth bishop of Holar, began to write somewhat out of the old books of the Æsir. Some got more and some less; that is why there are such different Eddas about. But men think that the Edda of Sæmund the historian is the fullest and best, for he was the older in point of time." Here the statement about Snorri's age would be derived from a statement in the Life of Bishop Jón respecting Gunlaug, who is there said to have written it for Gudmund the bishop, whilst Björn says that Snorri and Gunlaug are contemporaries: it is hence that Bishop Gudmund puts in an appearance here. Again, Jón Lærdi says that he is obliged to write from the shortest Eddas, for he has not yet been able to come across a larger one; he being evidently of opinion that there was, for instance, a far larger Gylfaginning than his [which is our text of today], but this he had never seen. A further proof (if it were needed) that Jón knew Hauksbók well, is found in his imitation of Merlinus Spa, called Kruck’s Spa, a prophecy of Iceland's fate and future history. Jón, with his cabalistic learning and happy love of popular superstition, is a figure of rather pathetic interest to one; his works are a storehouse of old words and phrases. He was a bit of a poet too in his own way; Ditty 51, vol. ii, is his, and it may well be that some of the fairy-tale poems, such as Kötlu-draumr, are by him. He was an artist too, a noted ivory-carver. Poor fellow! he lost most of his papers, which were taken and burnt, when he himself had a narrow escape from the mania for witch persecution which had reached Iceland too in the seventeenth century. He was what Jónson loved, a 'good hater.' He died in 1651. [1] Bök þessi heitir EDDA, hána hefir saman setta Snorri Sturlo sonr eptir þeim hætti sem her er skipað: er fyrst frá Ásom ok Gylfa [Ymi Cd.] þar næst Skaldskapar-mál ok heiti margra hluta. Síðast Hátta-tal er Snorri hefir ort um Hákon konung ok Skúla hertoga.—Cod. Ups. |

||

| 4.

The History of the Word 'Edda.' b. In and after 1642. |

||

We have now traced the story of the Edda among the scholars of the Icelandic Renaissance down to the great year 1642. How the whole of their ideas and theories were changed by the important discovery of Codex Regius at that date, remains now to be pointed out. The theory of Magnús respecting a double Edda paved the way for the acceptance of the new MS. as an Edda; Björn's fantasy supplied Sæmund's name (which, but for that, would never have been hit upon) as the author thereof. Let us see how the knowledge of the new-found MS. affected Björn. In the same MS. which contains Jón's treatise, is an Essay by Björn of Skardsa, entitled 'A certain little Compilation on Runes (Samtai um Runir), for the benefit of the learned, at Skardsa, 1642, B. J. S.' [Björn Jónson]. In this Essay for the first time appears the word Hávamál, and quotations unmistakably drawn from the songs in the Codex Regius MS. Hitherto there has been no citation from any one of the songs therein contained which one cannot point out as derived from other works. Here at last is sure and certain evidence that Björn has seen Codex Regius. How does he treat the songs? He speaks of them as dim, obscure, and difficult, needing interpretation, as of immense age, composed by the Æsir, etc. It would seem as if he had come across the MS. while writing his Essay, for he stops to explain what he is talking about, and to make clear to his readers what he means by the words he is using respecting it. For of course he must account for the book in some way. How he does so is this, he accepts the Magnús-Brynjólf theories as to a double Edda, and adapts them to this new find: this is the Edda we have all been talking about, the archetype or a piece of it, composed by Æsir and heroes, and written down by Sæmund. This Song-Edda I shall call Sæmund's Edda for distinction sake, and the Prose one I call henceforth Snorri's. This is what we gather clearly from such passages as this: "There are two books (he says) here in Iceland, which men commonly call Edda [a characteristic sweeping statement]. Now these books which are called Edda are very different indeed, for the book, which priest Sæmund Sigfusson the Wise has composed, is all in verse, and he has gathered together therein all the oldest, wisest, and most obscure songs which he could find in that tongue [the Danish tongue alluded to above in his Essay]. Many[1] have called the book Sæmund's Song-Book'," etc. [This last statement covers his own advance, or volt-face of theory, for it does not do to let people know one has not been omniscient, and a good broad assertion will always go down. There is of course no real intent to deceive here; it is only the old man's flighty fancy, not to say pet vanity, instinctively saving itself.] Again we have: "All that I have just stated comes from the Edda of Sæmund and its extremely old poems, prophecies and proverbs of wisdom, which are too long to insert here. This deep and obscure matter is treated of at great length in diverse places of the old poems in Sæmund's Edda." Surely in such passages we catch old Björn in the very act of christening his new-found treasure. In the same Edda he makes this final confession of faith as to Sæmund's authorship, the last edition, in fact, of his theories: "These (he says) are his works which men know for certain that he has composed and written: 1. Njala, which he has composed with great brilliancy. 2. Edda, which we call the Song-Edda. Master Brynjólf believes that this has for the most part perished; however, its yet existing fragments yield clear testimony to the learning and eloquence of this author. 3 He was also the first to begin the Odd-Annals from the creation of the world right down to his own day." One more passage will show that it is unmistakably Codex Regius which Björn now dubs Edda Sæmundi: "I will first say something about that obscure prophecy which Sæmund places first in his book, and which is named after the Völva." We need not pursue the list of notices of the Edda-Songs any further. We have seen the state of opinion just before and just after the discovery of Codex Regius. Subsequent scholars follow Brynjólf and Björn's theory, like sheep, without doubt or development [2] down to the present day. As to the order in which single songs of Eddic type turned up later, a few words may suffice. About the same time, or a few years later, the discovery of Codex Regius was supplemented by the discovery of a fragment of a MS. (A) which contains Ólaf Whitepoet's Essay on the Figures of Grammar, Snorri's Skáldskaparmál, the Thulur, and one sheet of poems, chief of which was the hitherto unknown Balder's Dreams. When Flateyjarbók came to light [in 1643] the one old poem it includes, the Hyndluljód, became known. In 1641 Bishop Brynjólf had bought a new second MS. of Snorri's Edda (r); in this the Grotti Song is preserved. The Sun's Song (Sólarljód) is first mentioned in Björn's Essay of 1642: 'as it is said in the old Sun's Song;' we have no information as to its vellum original, only paper copies having come down to us. The Lay of Menglad and Svipdag (Gróugaldur and Fjölsvinnsmál, aka Svipdagsmál) seems to have emerged later, as it is not cited by Björn; it is in like case, as to MSS., with the Sun Song. The first of all these early poems known was the Lay of Righ (Rígsþula), as it is in Codex Wormianus, which was certainly known before 1609 (when it is first mentioned by Magnús Ólafsson), for we gather that Ármgrím knew it as early as 1596. Heidrek's Riddles, to which Björn made a commentary (1641), were known first from Hauksbók, one of the mediæval MSS. which emerged earliest, quite as early as 1620. The introductions to the poems in Book IV note the earliest citations and the MS. authority of the other 'Eddic' poems; e. g. of Egil's three great poems Hofudlausn was the first known, before 1640, and the indefatigable Björn wrote a commentary on it. When Brynjólf had found the Codex Regius he had a copy taken on vellum, and inscribing it 'Edda Sæmundi multiscii,' sent it abroad. From it the title became spread on the continent, where scholars, as Árni Magnússon complains, accepted the superscription as an oracle not to be doubted. This vellum copy is lost. It came with the rest of Torfaeus' MSS. into Árni Magnússon's collection, and has disappeared, probably burnt in the Copenhagen fire, 1728. Beyond the momentary stir among the little knot of scholars, the influence of the newly-discovered 'Poetic Edda' was not very great; the scholars of the continent chiefly cared for them as throwing light upon 'Runic' matters, and the complete ignorance of their real worth is shown by the fact that the Editio Princeps of the Mythic Poems of Codex Regius is of 1787, only scraps and stray bits having been printed before, and that the earliest edition of the Heroic Poems is that of von der Hagen, 1812. The first complete edition of the whole is Rask's of 1818. In Iceland the influence is (beyond the lost copies alluded to, § 15) not very marked. Hallgrim Petersson's Commentary on some of the verses in Ólaf Tryggvason's Saga, a quaint work, quotes one of the Helgi Lays (but as from Gudrunakviða),—the earliest citation from these poems. There are traces of an acquaintance with the Didactic poems in his Passion Hymns, and his Sam-hendur clearly show a knowledge of them. Besides this, there is little or nothing save the forgery, Hrafnagaldr Óðins or Forspjallsljód, intended as an introduction to Balders Draumr, the oldest MS. of which goes back to 1670. [1] ‘Many’ here is Björn himself and nobody else; the national ‘we’ of the Three Tailors of Tooley Street. |

||

| § 5. Icelandic Diplomatics. | ||

There are four great collections of Icelandic MSS:— First, MSS. collected by Bishop Brynjólf and presented to the king, especially those which he sent him in 1662, now in the Royal Library of Copenhagen (the old MSS. Collection, 'Gamle Kgl. Saml.')—Codices Regii, about fifteen in all.* |

||

Secondly, the Collection of Árni Magnússon, the Father of Icelandic Letters, made between the years 1690 and 1728. —Codices Arna-Magnæni [ =AM. or Arna-Magn.]* Thirdly, the Upsala Collection, which was formed by Stephanius, of whom we have spoken above: from the hands of the De La Gardie family these MSS. passed to their present locale—Codices Upsalenses. Fourthly, the Stockholm Collection, of which the first part was brought together in Iceland in 1662 by Rugman; the second by Jón Eggertzson in 1682—Codices Holmenses. There was formerly a fifth collection, that of the University Library of Copenhagen, many from the library of Resenius/Peder Resen (Codices Reseniani). This collection was wholly destroyed by fire in 1728, save one MS. which had been lent out to Árni Magnússon. But luckily, under the auspices of Torfæus and other scholars, careful copies had been made of all the important Icelandic MSS. in this University collection, and these copies are now in the Arna-Magnaean Library—Codices Academici. These five collections absorbed all the Icelandic vellums and the best paper copies; and happily it was so, for the destruction of MSS. which went on in Iceland at the end of the seventeenth century would have left very little to be gathered if Árni had not come just when he did. As we have seen, all the vellums still in Bishop Brynjolf's possession at his death were scattered or mutilated or destroyed within a few years, and Árni could only procure fragments of what had been the finest collection in Iceland. Besides careless keeping, ill-usage, and bookbinding (for which the vellums were cut up, the loose plies serving to cover the wooden boards of modern printed books), which we may rank as active agents, Icelandic MSS. had, owing to the absence of libraries and national buildings, much to contend with,—the damp and smoke of the houses, which blackens and rots the parchment itself, and accounts for the dark, grimy, mouldering state of most MSS. Besides the dark, discoloured state of Icelandic MSS., there are other diplomatic signs which distinguish them. They are written in a systematically contracted form, which is quite unique in European diplomatics; hundreds of the ordinary words, and nearly all proper names, are expressed by abbreviations. This we may well suppose to have arisen from lack of parchment, but it was continued as a matter of calligraphy long after vellum was generally available, for however costly the MSS., however large the margin, Icelandic scribes never wrote otherwise. In the Norwegian MSS., unless they were written by Icelanders, the fashion did not obtain. One of the results of this is, that it requires a long and special training to read blurred passages, or to restore from the misreadings of extant MSS. the original words of the archetype. |