The Poetic Edda: A Study Guide

The Speech of the Masked One

[PREVIOUS][MAIN][NEXT]

[HOME]

MS No. 2365 4to [R]

AM 748 I 4to [A]

Normalized Text:

in Icelandic Poetry

“The Song of Grimnir”

The Yale Magazine, Vol. 16

“The Song of Grimner”

A glorious fabric strove to raise:

Skidbladner was the name they gave

The noblest bark that plough'd the wave.

Soon as the wond'rous toil was done,

They gave it to Niorder's Son.

To build Skithbladner,

strove, the best of ships,

For Asa Freyr, Niörd's all-worthy son.

in Edda Sæmundar Hinns Frôða

“The Lay of Grimnir”

in Corpus Poeticum Boreale

“The Sayings of the Hooded One”

43. Ivald’s sons

went in days of old

Skidbladnir to form,

of ships the best,

for the bright Frey,

Njörd´s benign son.

6. The sons of Iwald in the days of old set about building Skidblade, the best of ships, for the bright Frey, the blessed son of Niord.

in Edda Saemundar

“The Sayings of Grimnir”

in The Poetic Edda

“Grimnismol: The Ballad of Grimnir”

43. (42) Went the Wielder's sons of old

to build

Skidbladnir the wooden bladed,

best of all ships, for the bright god Frey,

ever bountiful son of Niord.

43. In days of old did Ivaldi’s sons

Skithblathnir fashion fair,

The best of ships for the bright god Freyr,

The noble son of Njorth.

in The Poetic Edda

“The Lay of Grimnir”

in The Elder Edda

“The Lay of Grimnir”

44. [In earliest times, Ivaldi's sons*

Skithblathnir, the ship, did shape,

the best of boats, for beaming Frey, the

noble son of Njorth.]

* Stanzas 44 and 45 are evidently interpolated; Skithblathnir, "the thin-planked."

42. The Sons of Invaldi ventured of old

To build Skidbladnir,

The best of ships, for bright Frey,

The nimble son of Njörd.

in The Poetic Edda

“Grimnir’s Sayings”

in The Poetic Edda, Vol. III: Mythological Poems

“The Lay of Grimnir”

made Skidbladnir,

the best of ships, for shining Freyr,

the beneficient son of Njörd.

43. Ivaldi’s sons

in days of old

set about shaping Stick-Leaf,

the best of ships,

for shining Freyr

Njörðr’s indispensable boy.

The Elder Edda: A Book of Viking Lore

'The Lay of Grimnir"

in The Poetic Edda, Revised

“Grimnir’s Sayings”

to create Skidbladnir,

The best of ships, for shining Frey

the capable son of Njörd.

went to create Skidbladnir,

the best of ships, for shining Freyr,

Njörd's beneficient son.

WORD STUDY:

What Sort of a Son is Frey to Njörd?

1851 C.P.: Niörd's all-worthy son.

1866 Thorpe: Njörd's benign son

1883 Vigfusson: the blessed son of Njörd

1908 Bray: ever bountiful son of Niord.

1923 Bellows: The noble son of Njorth

1962 Hollander: the noble son of Njorth

1967 Auden/Taylor: the nimble son of Njörd

1996 Larrington: the beneficient son of Njörd

2011 Dronke: Njörðr’s indispensable boy

2011 Orchard: the capable son of Njörd

I suspect that the 'translations' noble and nimble were poetic renderings chosen to alliterate with Njörd. The other translations more or less are derived from the actual meaning of the word found in the Cleasby-Vigfusson Dictionary:

nýtom (from njóta): to be of use.

Njóta, pres. nýt; pret. naut, nauzt, naut, pl. nutu; subj. nyti; imperat. njót:

... the primitive sense of this word was to catch, hunt, whence metaph. to use, enjoy; I. To use, enjoy, with gen.; neyta eðr njóta vættis, ...II. to derive benefit from or through the virtue of another person; -- to get advantage from, to avail oneself of one's greater strength, to receive help at one's hands.

Frey's a useful lad indeed!

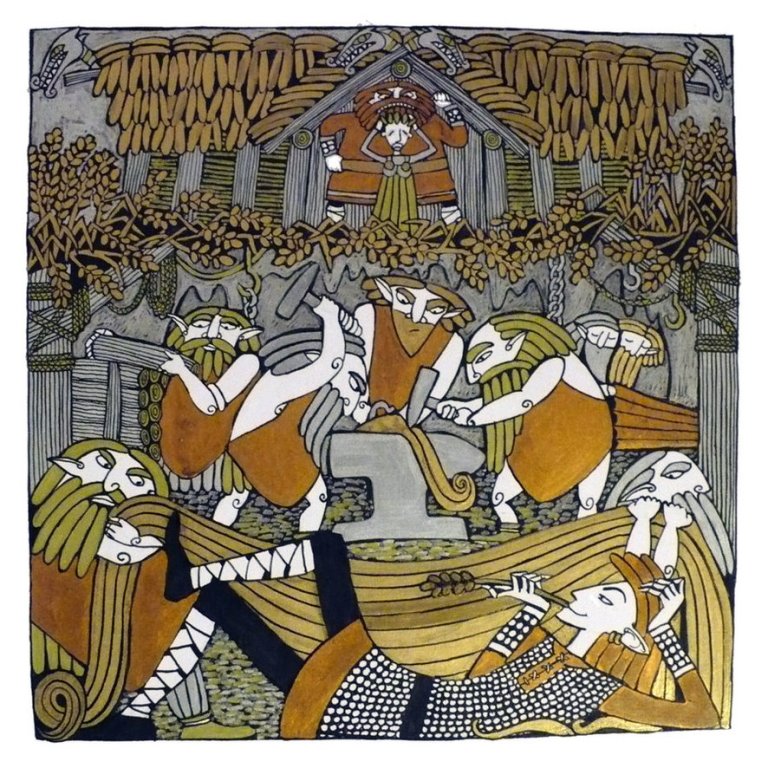

Ivaldi's Sons by Helena Rosova

FREYR AND THE ELVES

In verse 4, Thor's home Thrudheim is said to lie nearest to the Æsir and the Alfar (elves), and then in verse 5, Ull's home Ydalir (Yewdales) is named. In the second half of verse 5, "the gods, in ancient days, gave Alfheim to Frey as a tooth-gift". In verse 43, "Ivaldi's sons, in ancient days, create Skidbladnir, the best of ships, for Frey." Thematically, both verses describe gifts given to Frey by elves "in the earliest days," i árdaga. Side by side in the original language, a comparison makes this more apparent:

|

|

|

||

|

5. Ýdalir heita, |

43. Ívalda synir |

Esoterically, the framing device of this poem is concerned with the acquisition of kingship, as a blessing of the gods— particularly Odin, who initally favors Geirrod, who becomes king. At the end of the narrative, King Geirrod falls on his sword, and his nephew—young Agnar— ascends to the throne under Odin's guidance. The point of this poem seems to be the coronation of a just king.

This double invocation of Ull, Frey and the elves at the beginning and the end of the poem may suggest the opening and the closing of a ritual ceremony. In between Odin has conveyed geographical knowledge of the Old Heathen Cosmos and a symbol-laden tour of the afterlife. He has imparted the necessary esoteric wisdom for the heir apparent to ascend to the throne.

Immediately before he breaks into the wisdom verses of Grímnismál, Odin accepts the gift of a cool drink from Agnar, the boy who will be king. Immediately afterward, the "masked" speaker (Odin) reveals his identity as the Father of the Gods, the kingmaker himself, through a series of names. Foreshadowing this, the poem has already used the name Odin six times, more than any other proper name in the poem. After Odin has revealed himself, he speaks his name three more times for a total of nine, a mystic number in the lore alluding to the nine worlds in the tree— the totality of the universe.

An invocation of Frey and the elves at the beginning and end of the rite of kingship is both intentional and appropriate. As we shall see below, Frey and the elves are closely associated with kingship. Kings especially were responsible for the fertility of the land. In Gylfaginning 24, Snorri describes Frey as "Hann ræðr fyrir regni ok skini sólar ok þar með ávexti jarðar, ok á hann er gott at heita til árs ok friðar. Hann ræðr ok fésælu manna, "he rules over the rain and the shining of the sun, and with it the fruit of the earth; and it is good to call on him for fruitful seasons and peace. He governs also the prosperity of men." And he later says that Frey was known as árguð ok fégjafa, "harvest-god and the wealth-giver" (Skáldskaparmál 14). As we shall see in the next verse, the elves are closely associated with weather magic.

| Freyr and Kings |

The late 13th or early 14th century Gunnars þáttr helmings, preserved in the Flateyjarbók, contains a religious parody recounting the plight of a man named Gunnar who flees from Norway to Sweden in 995 AD, the first year of Olafr's reign, taking refuge there with a priestess of Frey. He accompanies her as she travels among her people giving arbót ('help with the crops'). In this procession, Frey represented by a wooden idol and his wife, the priestess, ride in a horse-drawn wagon through the countryside, just as Nerthus rides in a covered wagon drawn by cattle, attended by a priest of the opposite sex. The time of the procession is marked with peace and feasting. Gunnarr bravely leads the horse through a blizzard, but when he requires rest and sits in the wagon, Frey attacks him. As they wrestle, Gunnar vows to return to King Olafr and the Christian faith should he survive. At once, “the devil” exits the wooden idol and takes flight allowing Gunnar to smash the statue to pieces. Impersonating Frey, Gunnar impregnates the priestess before returning to Norway and Christianity. Here too, good harvests are attributed to the god.

Intended to make light of the pagan past, this story instead confirms many of the details of the Nerthus cult as described by Tacitus: an idol is drawn through the countryside in a wagon, attended by a priest of the opposite sex; only the priest can sense the presence of the god and touch the idol; during the procession, peace reigns. At the very least, this tale provides evidence that people in the early fourteenth century accepted the idea that heathen religious processions conveying effigies of heathen idols through the countryside were still taking place during the reign of Olaf Tryggvasson. In Christian times, images of saints were drawn through the fields for a similar purpose.

Besides Nerthus, many examples of divinities or kings being pulled through the countryside in a wagon are found throughout northern europe. Jacob Grimm catalogs many of these in his Deutsche Mythologie. In some traditions, the land vehicle was a ship. This may explain Skidbladnir's nature as a collapsable wooden ship. The oldest instance we have of the veneration of a Germanic diety in a ship comes from Tacitus' Germania, chapter 9:|

Pars Sueborum et Isidi sacrificat: unde causa et origo

peregrino sacro, parum comperi, nisi quod signum ipsum in modum

liburnae figuratum docet advectam religionem. |

Part of the Suebi sacrifice to Isis as well. I have little idea what the origin or explanation of this foreign cult is, except that the goddess's emblem, which resembles a light warship, indicates that the goddess came from abroad. |

It is unlikely that this "Isis" was related to the cult of the Egyptian goddess, whose range is well mapped throughout the ancient world. More likely is that Tacitus' informers witnessed a ship procession devoted to a native Germanic goddess. Noteworthy in this regard, the 3rd century Germanic goddess Nehalennia named on 160 votive altars from the second and third centuries. Twenty-eight of these are found on the Rhine island of Walchern in the Netherlands. A similar number were discovered in 1971-72 at Colijnsplaat on the island of Noord-Beveland. Two more were found in the Cologne-Deutz area. She is most often depicted resting against the prow of a ship or an oar.

The twelfth century monk Rudolfus from the Abbey of St. Trond, in his account of a Carnival festival in the district of Jülich, in Lower Germany pens a detailed report about the year 1133 (Chronicon Abbatiae S. Trudonis, Book XI). In a forest near Inda (in Ripuaria), a ship was built, set upon wheels, and drawn about the country by "rustic folk" who were yoked to it; first to Aix-la-Chappelle, then to Maestricht, where mast and sail were added, and up the river to Tongres, Looz, and so on, everywhere with crowds of people assembling and escorting it. Wherever it stopped there were joyful shouts, songs of triumph and dancing round the ship kept up till far into the night. The approach of the ship was made known in advance to the towns; the people opened the gates and went out to meet it.

Ship-processions at the beginning of spring continued in various parts of Germany to the end of the Middle Ages. The custom of drawing a plough seems, however, to have been more widespread among the ancient Germans, and has survived down to the present day in some German villages on Shrove Tuesday, more often on Plough Monday. In some districts of Germany, a ship was drawn in addition to the plough. In Ulm on the Danube a ship-procession took place annually down to 1530 when an order by the city council put a stop to it. A ship-cart was drawn in the Nuremberg procession of maskers ("Schembartlauf") from 1475 on. A closer analysis of the content of these rituals, such as the Anglo-Saxon Aecerbot, demonstrates that these wagon and ship processions at the beginning of spring were closely associated with the communal "opening of the fields" that would ensure a successful harvest.

In ancient Sweden, a king was invested with a certain quality of "luck". The fertility of the land depended upon it. Ynglingasaga 15 says that the Ynglinga king Domaldi was sacrificed after three years of starvation and misery (sultr ok seyra) during his reign in Svetjud. The first year, the Svear made a huge sacrifice of oxen, but nothing improved. The second year, they sacrificed humans and the crops were worse. In the third year, Svear in great numbers came to Uppsala at the time of sacrifice. The chieftains held council and agreed that their king Domaldi was the cause of the famine, and so resolved to sacrifice him and sprinkle the land with his blood for better seasons (blóta til árs sér). Historia Norwegiæ (Ed. Storm p. 98) goes so far as to say that Domaldi, one of the Ynglinga kings, "was hung and offered by the Svear (Swedes) to the (Roman) goddess Ceres to give good crops."Surviving stanzas of Vellekla by Einar (c. 990 AD), preserved in Fagrskinna and Olafs Saga Tryggvasonnar, praise Hakon Jarl, who re-established pagan practices after a brief Christian conquest. Fagrskinna's author comments that Hakon performed the sacrifices with more strictness than before and soon the earth flourished. The crops of grain and herring improved, and Hakon grew rich.

The cult was a means of consolidating social structures. The elite used cult feasts as a form of repayment, while the farmers needed the cult of the ruler for protection and for ritual matters. Thus there was a reciprocal relationship between the ruling class and the peasants. The idea of people paying tribute to their ruler appears in Hakonar Saga goda, ch. 14, where Snorri states:

"It was ancient custom that when sacrifice was to be made, all farmers were to come to the hof and bring along as much food as they needed while the feast lasted. At the feast, all took part in ale drinking. Also all kinds of livestock were slaughtered in connection with it, horses too."

Adam of Bremen describes the ritual nature of this gathering:

|

Sacrificium itaque tale est. Ex omni animante, quod

masculinum est, novem capita offeruntur, quorum sanguine deos

placari mos est. Corpora autem suspenduntur in lucum, qui

proximus est templo. Is enim lucus tam sacer est gentilibus, ut

singulae arbores eius ex morte vel tabo immolatorum divinae

credantur. Ibi etiam canes et equi pendent cum hominibus, quorum

corpora mixtim suspensa narravit mihi aliquis christianorum 72

vidisse. Ceterum neniae, quae in eiusmodi ritu libationis fieri

solent, multiplices et inhonestae ideoque melius reticendae.

Schol.137

Schol. 137. Novem diebus commessationes et

eiusmodi sacrificia celebrantur; unaquaque die offerunt hominem

unum cum ceteris animalibus, ita ut per novem dies 72 fiant

animalia quae offeruntur. Hoc sacrificium fit circa aequinoctium

vernale. |

The sacrifice is of this nature: of every living thing that is male, they offer nine heads with the blood of which it is customary to placate gods of this sort. The bodies they hang in the sacred grove that adjoins the temple. Now this grove is so sacred in the eyes of the heathen that each and every tree in it is believed divine because of the death or putrefaction of the victims. Even dogs and horses hang there with men. A Christian told me that he had seen 72 bodies suspended promiscuously. Furthermore, the incantations customarily chanted in the ritual of a sacrifice of this kind are manifold and unseemly; therefore, it is better to keep silent about them. 137 Note 137: Feasts and sacrifices of this kind are solemnized for nine days. On each day they offer a man along with other living beings in such a number that in the course of the nine days they will have made offerings of seventy-two creatures. This sacrifice takes place about the time of the vernal equinox. |

This is most certainly a Germanic rite. We find it elsewhere among the Scandinavian heathens. The German historian Thietmar of Merseburg, writing in the beginning of the eleventh century, relates as follows about the heathen practices of the Danes:

"There is a place in those regions which is the capital of the realm, called Lederun, in that part of the country which is called Selon where, every ninth year, in the month of January, somewhat later than our Christian Yuletide, they assemble together and sacrifice to their gods 99 men and as many horses, dogs, and cocks, believing that these will be of service to them in the realm of the dead and atone for their misdeeds."

There can be no doubt that Selon here represents Zealand (Old Norse Selund) and that Lederun stands for Lejre (Old Norse at Hleiftrum, Old Danish at Ledhrum).

Snorri mentions a winter market at Uppsala held at the same time as the cult feast and Thing of the Svear. This is probably identical with the Disþing attested in Upplandslagen (1296 AD). At Uppsala, the name of the market, Disþing, also indicates a pre-Christian assembly attached to the cult of the Disir.

|

Í Svíþjóðu var það forn landsiður meðan heiðni var þar að

höfuðblót skyldi vera að Uppsölum að gói. Skyldi þá blóta til

friðar og sigurs konungi sínum og skyldu menn þangað sækja um

allt Svíaveldi. Skyldi þar þá og vera þing allra Svía. Þar var

og þá markaður og kaupstefna og stóð viku. En er kristni var í

Svíþjóð þá hélst þar þó lögþing og markaður. En nú síðan er

kristni var alsiða í Svíþjóð en konungar afræktust að sitja að

Uppsölum þá var færður markaðurinn og hafður kyndilmessu. Hefir

það haldist alla stund síðan og er nú hafður eigi meiri en

stendur þrjá daga. Er þar þing Svía og sækja þeir þar til um

allt land. |

In Svithjod it was the old custom, as long as heathenism prevailed, that the chief sacrifice took place in the month Gói (sometime around Feburary 15th until March 15th) at Upsala. Then sacrifice was offered for peace, and victory to the king; and thither came people from all parts of Svithjod. All the Things of the Swedes, also, were held there, and markets, and meetings for buying, which continued for a week: and after Christianity was introduced into Svithjod, the Things and fairs were held there as before. After Christianity had taken root in Svithjod, and the kings would no longer dwell in Upsala, the market-time was moved to Candlemas, and it has since continued so, and it lasts only three days. There is then the Swedish Thing also, and people from all quarters come there. |

Adam of Bremen describes the heathen temple at Uppsala in 10th century Sweden as follows:

|

Capitulum 27: Omnibus itaque diis suis attributos habent sacerdotes, qui sacrificia populi offerant. Si pestis et famis imminet, Thorydolo lybatur, si bellum, Wodani, si nuptiae celebrandae sunt, Fricconi. Solet quoque post novem annos communis omnium Sueoniae provintiarum sollempnitas in Ubsola celebrari. Ad quam videlicet sollempnitatem nulli praestatur immunitas. Reges et populi, omnes et singuli sua dona transmittunt ad Ubsolam, et quod omni poena crudelius est, illi qui iam induerunt christianitatem, ab illis se redimunt cerimoniis. |

Chapter 27: For all their gods there are appointed priests to offer sacrifices for the people. If plague and famine threaten, a libation is poured to the idol Thor; if war, to Wotan; if marriages are to be celebrated, to Frikko. It is customary also to solemnize in Uppsala, at nine-year intervals, a general feast of all the provinces of Sweden. From attendance at this festival no one is exempted Kings and people all and singly send their gifts to Uppsala and, what is more distressing than any kind of punishment, those who have already adopted Christianity redeem themselves through these ceremonies. |

During these feasts and gatherings it was convenient for rulers to gather tribute from the people (especially the chieftains) and exchange gifts. Rulers took pledges of military service, loyalty, goods, raw materials, labor and other services in exchange for protection and prosperity. The ruler was looked upon as the cult leader and the link between the people and their gods. Adam of Bremen says that the people and their leaders were obligated to visit or send their gifts to Uppsala during the major calanderic sacrifices, of which there were three held annually in the Spring, Summer and Winter. Snorri's Ólafs Saga helga ch. 77 in Heimskringla also refer to the great sacrifice at Uppsala. Both Adam and Snorri indicate that the assembly gathered at the same time as the sacrifical feasts at Uppsala, in Feburary-March. The ruler was given presents and tributes for the cult feasts he made for his people throughout the year.

On the local level, Eyrbyggja Saga ch. 4 and Landnámabók say that all men must pay tribute (tolla) to the sanctuary. In reference to a local hof in Egils Saga ch. 84, the author says "all men pay a hof-toll for that" (allir menn guldu hoftoll till). In return, the cult leader, who may be the clan patriarch or local military ruler, is expected to perform the necessary rituals to keep the land prosperous. By giving and receiving gifts in public at ritual feasts the ruler tied himself to the people. The queen acting as his delegate, "the lady with the mead cup", fortified the ties between the ruler and his retainers, recognizing each in order of importance. In Old English the ruler's hall is sometimes called the gif-haell, "the gift-hall", or gold-sele, "hall of gold", and the ruler is characterized as a gift-giver: "treasure-giver", "ring-giver", "ring-breaker", etc. A good ruler is seen as a distributer of wealth.

As the archaeological work at Hofstaðir in Iceland demonstrates, these "temples" are best seen as large communal halls, containing the living quarters of the ruling elite, where sacrifical slaughter and communal feasts were regularly performed.

Like Freyr, elves are also associated with kingship. The most famous example is that of Olaf Geirstada-alfr, "Olaf the elf of Geirstad" as told in Ólafs Saga Helga, ch. 106 preserved in the Flateyjarbók. Regarding King Ólaf Haraldsson, the source informs us that his contemporaries believed that he was the ancient king Ólaf Geirstada-alf reborn. The king, it adds, had heard this but labeled it heathen superstition. Ólaf Geirstadaalf was reputed to be the uncle of Harald Fairhair, a descendant of the Ynglings and the first king to unify Norway. The story of Ólaf Geirstadaalf, as found in the Flateyjarbók says that he ruled in two counties, Upsi and Vestmar. His throne was in Geirstadir in Vestfold. According to the Fornaldarsaga known as Af Upplendinga Konungum. (“Of the Kings of Uppland”), he was unusually large, strong, and handsome in appearance. It is said that he defended his kingdom bravely against foes, and that under his leadership, good harvests and peace, for the most part, prevailed so that the people multiplied greatly.

Yet, once he was troubled by a worrisome dream. Before an assembly gathered for this purpose, King Ólaf revealed that he had dreamed that a big, black ox from the east traveled around his entire country, killing so many people with its noxious breath that those who died were as numerous as those that survived. The ox even killed him and his retinue. Ólaf interpreted the dream for them, saying: “Long has peace reigned in this kingdom and good harvests, but the population is now greater than the land can bear. The ox means that a plague will come to the country from the east and cause many deaths. My retinue will also die of it and even I, myself.” He requested that the people not sacrifice to him after his death. In time, King Ólaf's dream came true. The people laid him in a mound with many treasures, and later, when bad harvests came, the people sacrificed to him, despite his prohibition, and called him Geirstada-alf (“the elf of Geirstad”). This story, told in the Flateyjarbók, is associated with a verse in Ynglingatal 38 occurring in variants in the Flateyjarbók and Heimskringla. These stories of Ólaf the elf were not written later than 1200, and thus are among the older stories of St. Ólaf in existence. They contain remarkable parallels to the cult of Freyr.

Details concerning Freyr's cult can be gathered from diverse sources. In the Flateyjarbók tale, Freyr is called blótguð svía, the “sacrificial god of the Swedes.” In Ynglingasaga 4, a euhemerized Odin appoints Njörd and Freyr as blótgoða (sacrificial priests) among the Aesir. Njörd's daughter, Freyja, is their blótgyðja (sacrificial priestess). In Víga-Glum’s Saga, ch. 9, a man named Thorkel goes to Freyr's temple and offers the god an ox. In Brandkrossa þáttur, ch. 1, a farmer kills and cooks a bull, dedicating the entire feast to Freyr. In Hyndluljóð, Ottar reddens the Freyja's altar with ox blood (nauta blóði). In the first book of Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Dancorum, the hero Hadding institutes the annual festival known as the Fröblot, Frø being the Danish equivalent of Freyr, in which only “dark-colored” (furvis) victims were sacrificed, recalling the black ox of Ólaf Geirstadaalf's dream. The color black, commonly associated with death or evil in Christian iconography, was the color of fertility and the soil in Old Europe. In Hrafnkels Saga Freysgóða, Freyr's priest Hrafnkel dedicates half of all his best livestock to the god (ch. 2). His most valuable animal was a dun stallion with a dark tail and mane, and a dark stripe down its back (ch. 3). He loved this horse so much that he dedicated half of it to Freyr, naming it Freyfaxi.

The nickname alfr (elf) applied to King Olaf buried in a gravemound has suggested to some scholars like E.O.G. Turville-Petre (Myth and Religion of the North, p. 231) that the alfr have come to be identified with the dead. This in turn is supposed to explain how men can be descended from elves. From the existing examples in the lore, however, the connection appears to be more direct.

The identity of the "black-elves" or dwarves known as Ivaldi's sons can be established from the surviving references. They are three in number, commonly called Thjazi, Egil and Idi. Elsewhere Thjazi is known as the giant who kidnaps Idunn. For the evidence demonstrating the connection between the "giant" Thjazi and the "elf" artist of the same name, see The Æsir and the Elves. The artisans known as the Sons of Ivaldi are the offspring of an elf father and a giantess mother, allowing them to thus be characterized by both tribal affiliations, depending on their current loyalties. They were once friends of the gods, producing treausres for them, and because of Loki's perfidy became their most bitter foes, causing devastating destruction on the gods' creation, before the Æsir were able to slay Thjazi and reconcile with the elf-clan.

As part of this reconciliation, after Thjazi's death, Frey's father Njörd marries Thjazi's daughter, Skadi. In Heimskringla, Hakon Jarl claims direct descent from her. In Ynglingasaga chapter 9, Snorri informs us:

|

Njörður fékk konu þeirrar er Skaði hét. Hún vildi ekki við hann samfarar og giftist síðan Óðni. Áttu þau marga sonu. Einn þeirra hét Sæmingur. Um hann orti Eyvindur skáldaspillir þetta: Þann skjaldblætr skattfæri gat ása niðr við járnviðju, þá er

þau mær í Manheimum skatna vinr og Skaði byggðu. Til Sæmings taldi Hákon jarl hinn ríki langfeðgakyn sitt.

|

Njörd took a wife called Skadi; but she would not live with

him and married afterwards Odin, and had many sons by him, of

whom one was called Saeming; and about him Eyvind Skaldaspiller

sings |

The Scandinavian king Hakon is descended from Thjazi's daughter Skadi. Based on the association of Frey and the elves, and the line of the Yngvi kings, it seems likely that at least some of these kings claimed direct descent from elves, such as Skadi's father Thjazi. This can be demonstrated in another way as well. |

Skadi The Huntress, Daughter of Thjazi by Howard David Johnson |

| Elves and Kings |

According to at least one record, early heathen "converts" to Christianity preferred the name of an elf to the name of a Biblical patriarch for their newly-crowned king. So much so, they were willing to riot until it was changed. Fagrskinna, A Catalogue of the King's of Norway, by Alison Finlay, p 146:

| "It is explained in Heimskringla that the name Jakob, chosen because he was born on the day before the feast day of St James the Apostle (25th July), was considered inappropriate for a king of the Swedes and was changed to Önundr, when he succeded his father. (Hkr II, 130, 156)." |

Chapter 88 of Ólafs saga Helga (Hollander tr.) states:

| Enn gátu þau son og var fæddur Jakobsvökudag. En er skíra skyldi sveininn þá lét biskup hann heita Jakob. Það nafn líkaði Svíum illa og kölluðu að aldregi hefði Svíakonungur Jakob heitið. | They still had another son born on the day before Saint Jacob's Mass. When the boy was to be baptized, the bishop called him Jákob. That name ill-pleased the Swedes. They said that no Swedish king had borne that name." |

And in chapter 94, it is clear that this movement is lead by the Uppland Swedes:

|

Freyviðr svarar: "eigi viljum vér Upsvíarnir, at konungdómr gangi ór langfeðga-ætt inna fornu konunga á várum dögum, meðan svá góð faung eru til, sem nú er. Oláfr konúngrá tvá sonu, ok viljum vér annan hvárn þeira til konungs." "...Eptir þat létu þeir brœðr, Freyviðr ok Arnviðr, leiða

fram á þingit Jákob konungs-son ok létu honum þar gefa

konungs-nafn, ok þar með gáfu Svíar honum Önundar nafn, ok var

hann svá síðan kallaðr, meðan hann lifði." |

Freywith answered: "We Uppland Swedes do

not wish that in our days the crown go from the line of the

ancestors of our ancient kings while there is such good choice

as we have. King Olaf has two sons and we desire one of them to

be king." "...Therefore the brothers Freyvith and Arnvith had the king's son Jákob brought before the assembly and had him given the title of king. at the same time the Swedes gave him the name Onund, and that name he bore till his death." |

In the poems of the Elder Edda, we find the name Önund once, and then applied to an elf-prince. In Völundarkviða 2, Önund or Anund appears as an alternate name for Völund, the elf-prince. The Swedes prefer the name Önund, a byname of Völund the elf-prince over Jacob, the name of an Old Testament patriarch. Thus, a designation invoking an elf from heathen mythology was considered appropriate for royalty among the ancient Swedes, while a the name of a patriarch from the new religion was not. For this, they rest on tradition. No Swedish king had borne such a name before. No doubt, by their actions, the people were probably only nominally Christian, rooted fast in their ancient custom, in which the bounty of the land was directly tied to the ruler's relationship with the old gods.

In a stanza from the poem Velleka preserved in Fagrskinna, chapter 17, we find the name Miðjungr used as a base in a kenning for warrior. The kenning reads: leikmiðjungr odda: 'Miðjungr of the play of spear'.

Here we would expect to find the name of a god or legendary hero. The translator of the text, Alison Finlay, who understands Midjungr as a giant's name is surprised by this and remarks:

| "Miðjungr is listed as a giant's name in one of the þulur attached to Snorra Edda (Skáld I, 111), but it is not known how it comes to be used as a base word in kennings for 'man'." |

In Skáldskaparmál 39, Snorri informs us:

| Af þessum heitum hafa skáldin kallat manninn ask eða hlyn, lund eða öðrum viðarheitum karlkenndum ok kennt til víga eða skipa eða fjár. Mann er ok rétt at kenna til allra ásaheita. Kennt er ok við jötnaheiti, ok er þat flest háð eða lastmæli. Vel þykkir kennt til álfa. | It is also correct to paraphrase man with all the names of the Æsir; also with giant-terms, and for the most part the latter is for mocking or libellous purposes. Periphrasis with the names of elves is held to be favorable. |

We see no reason to suspect the name Miðjung is used in mockery here. So how can this be explained? How can the name of an apparent giant be used as the basis for a warrior-kenning? Snorri adds that the use of an elf name as a baseword in a kenning is favorable.

Of interest, we find the name Miðjungr associated with Thjazi in the skaldic poem Haustlöng 8/4-8. When Thjazi, in eagle guise, picks up Loki whose hand is stuck to a pole, and flies off with him, dragging his body over trees and rocks until he begs for mercy, the poem describes the scene this way:

| þá varð Þórs of rúni (þungr vas Loptr of sprunginn) mölnaut, hvats mátti, miðjungs friðar biðja. | Then Thor's confidant (Loptr [Loki] was heavy and near dead with exhaustion) was obliged to beg Midjung's meal-companion for whatever deal he got." |

In Haustlöng, preserved within manuscripts of Snorri's Edda, Thjazi is called miðjungur, which is commonly taken as a proper name Midjung. He is further designated as Þórs of runni, "he who caused Thor to run," (Codex Regius) or as Þórs of rúni, "he who was Thor's friend,"(Codex Wormianus). The manuscripts vary here, but each kenning is explainable in the context of the myth of the Ivaldi sons.

According to the later reading Thjazi once had been Thor's ofrúni, Thor's trusted friend. This reading finds its support in the myths if Thjazi is a Son of Ivaldi, a treasure-maker for the gods, particularly Thor. When Loki cut off Sif's hair, he went to the Sons of Ivaldi first to ask them favor in replacing it, demonstrating their initial goodwill and friendship toward the Æsir. Even though only one of the two variant readings can be the original, both are found in ancient manuscripts and both can be mythologically justified.

Thjazi is commonly identified as the giant who kidnapped Idunn. As shown above, Thjazi the son of Allvaldi and Ölvaldi, is likely one of the famous Sons of Ivaldi. As an alternate name of Thjazi, Midjung has been identified as a "giant's name", and thus been added to a list of jötun-heiti in Skáldskaparmál. In the mythology, Thjazi is a son of the elf Ivaldi and a giantess named Grep. As a "Son of Ivaldi" he was an elf-prince and mastersmith, who made golden treasures for the gods. As the loser of the Contest of the Artists instigated by Loki, he becomes a bitter enemy of the gods and plots his revenge. Then he is called a "jötun". He first attacks Loki and then finds a way to effect all of the gods by removing his half-sister Idunn and her golden apples from Asgard. As a skilled artist, his sister's youth-perserving apples may have been a product of his own forge. He is long able to avoid the gods in his mountain halls. Grímnismál 11 names his home Thrudheim (now occupied by his daughter Skadi) among the homes of the gods. In Icelandic, a labyrinth is known as Völundarhús, Völund's house. It is there he likely kept Idunn. She is probably the mother of Thjazi's daughter Skadi, and thus is received favorably by the gods.In an unprecedented event, when the "giant" Thjazi is killed, his daughter Skadi arrives in Asgard and demands compensation for his death. This had not happened before or since, which is remarkable considering the number of giantesses that Thor alone killed. Skadi's father must have been a being in high standing, because the Æsir comply by allowing her her choice of husband from among the gods. Of them all she desired Baldur most. However, the gods imposed this condition. They would be veiled, and she could only choose them by the natural beauty of their feet. Njörd, the sea-god, won the competition. Thiers was an unhappy union. Regardless, it is worthy to note that she was treated kindly by the gods, and compensated handsomely, despite the outcome.

Similarly, when the gods kill Thjazi within the walls of Asgard, Odin or Thor makes stars of his eyes, as if to honor him. Prior to this, the honor of having a star made from a part of one's body was reserved for Thor's friend Aurvandil, whose frost-bitten toe Thor broke off and threw into the heavens, where it is known as 'Aurvandils Toe.' Perhaps as a reference to this, Völundarkvida informs us that Völund's eyes flash like a serpents when he awakes and finds himself in chains and his treasures distributed among his captor's family.

Can Thjazi be both an elf and a jötun? Is this possible? If we accept that the giant Thjazi is identical to the elf-prince Völund, this is easily explainable. All we need do is look at their parentage. Thjazi is the son of the elf Ivaldi (Hrafnagaldur Óðins 6) and a giantess named Grep (Haustlöng). The same confusion surrounds Völund's parentage in the sources. In the Poetic Edda, Völund is an elf-prince, son of a Finn-King. In Thidreks Saga of Bern, Velund (Völund) is said to be a giant and his mother is said to be a mermaid. In Germanic folklore, Völund (Wayland) himself must have been considered to have been of giant stature considering the natural rock formations named as being his workshop. Yet, Völundarkviða, the oldest record of him, clearly identifies him as an elf-prince.

Although Thjazi-Miðjung has giant-blood in his veins (on his mother's side), he is the son of the elf Ivaldi, and therefore himself a prince of the elves. Völundarkviða confirms this. The names of gods and goddesses, even valkyries, can be used as the base in kennings to indicate honorable men and women. Snorri in his Edda says that the names of elves can also be used as base names for warriors, and that this is considered favorable. This suggests that the elves themselves, like gods, were held to be honorable and worthy of comparison. The use of Elves' names was a designation of distinction. Conversely, the substitution of giants' names in kennings was considered mockery.

This probably is because the elves were seen as a third divine class. The three castes of gods were the Aesir, the Vanir and the Alfar. Each were likely founded by one of the Sons of Borr. Odin formed the Æsir, his brothers Vili and Vé, also called Lodur and Hoenir, most likely founded the Vanir and the Alfar respectively. See Toward the Origin of the Vanir and the Alfar and Heimdall: Bridging the Gap [Interlude: Odin's Brothers].

Borr's sons slay Ymir by Giovanni Casselli (1977) |

Thjazi is said to be the son of Allvaldi and of Ölvaldi, which both seem to be variant names of Ivaldi. Hrafnagaldur Óðins 6 identifies Ivaldi as an elf, and the father of Idunn. It says that he has two sets of children, a younger and an older set. In Grímnismál and in the Prose Edda, Ivaldi is the father of the famous sons who crafted treasures for the gods such as Skidbladnir. In Haustlöng, which alludes to the myth of Thjazi and Idunn, Thjazi owns several magic objects: a decoy-reindeer, a pole that cannot be released, a fire that won't cook, and a feather-guise. Völund escapes Nidhad's smithy in a flying device of his own making. In Thidreks Saga of Bern, Velund's brother Egill the archer collects feathers for its construction. The same scene may be depicted on one panel of the Franks Casket. As the creator of an eagle-guise, later worn by Odin, Thjazi may be the author of all the mythic feather-guises, predominately worn by the goddesses such as the falcon-dresses of Frigg and Freyja, as well as the swan-dresses of his and his brothers' wives. The forge of the Sons of Ivaldi are the most likely source of these mythic treasures.

Since the elves are closely associated with Freyr and the Yngvi line through the line of Thjazi and his daughter Skadi, it is appropriate that Odin evokes them at the beginning and the end of the kingship ritual that underlies the action of Grímnismál.

The Cult of Freyr and Freyja

[PREVIOUS][MAIN][NEXT]

[HOME]