Svaðilfari, Sleipnir,

The Sun, The Moon and Freya

by Dr. Christopher Johnsen

© 2014

[HOME]

|

It would seem to follow that farming technology was not just limited to knowing things about the earth and plants but also knowledge of the stars, planets, sun and moon and how the heavenly bodies can be used to create an accurate calendar so that agriculture could flourish. As Kevin Jones says, “Measuring and structuring time thus involves an element of prediction for purely practical agricultural purposes, and may therefore be considered an agricultural technology.”(1)

An important story along these lines is found in chapter 42 of Gylfaginning, where Har (“High”) tells a story set at the beginning of the gods' days, when they created Midgard and built Valhal. It is about an unnamed builder who offered to build a fortification for the gods that will keep out bergrisum ok hrímþursum, "hill giants and frost giants," in exchange for the goddess Freyja, the sun, and the moon. After some debate, the gods agree to this, but place a number of restrictions on the builder, including that he must complete the work within one winter with the help of no man. The builder accepts, but only after securing the use of his horse to help build the wall, (A. Brodeur translation):

“XLII. Then said Gangleri: "Who owns that horse Sleipnir, or what is to be said of him?"

Hárr answered: "Thou hast no knowledge of Sleipnir's points, and thou knowest not the circumstances of his begetting; but it will seem to thee worth the telling. It was early in the first days of the gods' dwelling here, when the gods had established the Midgard and made Valhall; there came at that time a certain wright and offered to build them a citadel in three seasons, so good that it should be staunch and proof against the Hill-Giants and the Rime-Giants, though they should come in over Midgard. But he demanded as wages that he should have possession of Freyja, and would fain have had the sun and the moon. Then the Æsir held parley and took counsel together; and a bargain was made with the wright, that he should have that which he demanded, if he should succeed in completing the citadel in one winter. On the first day of summer, if any part of the citadel were left unfinished, he should lose his reward; and he was to receive help from no man in the work. When they told him these conditions, he asked that they would give him leave to have the help of his stallion, which was called Svaðilfari; and Loki advised it, so that the wright's petition was granted. He set to work the first day of winter to make the citadel, and by night he hauled stones with the stallion's aid; and it seemed very marvelous to the Æsir what great rocks that horse drew, for the horse did more rough work by half than did the wright. But there were strong witnesses to their bargain, and many oaths, since it seemed unsafe to the giant to be among the Æsir without truce, if Thor should come home. But Thor had then gone away into the eastern region to fight trolls.

|

The unnamed bergrisi ("hill giant") builds a borg (“citadel”) or wall around Asgard. A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city with higher walls than the rest which is supposed to be the strongest part of the defensive system. It is positioned to be the last line of defense if the rest of the fortifications are breached.

"Now when the winter drew nigh unto its end, the building of the citadel was far advanced; and it was so high and strong that it could not be taken. When it lacked three days of summer, the work had almost reached the gate of the stronghold. Then the gods sat down in their judgment seats, and sought means of evasion, and asked one another who had advised giving Freyja into Jötunheim, or so destroying the air and the heaven as to take thence the sun and the moon and give them to the giants. The gods agreed that he must have counselled this who is wont to give evil advice, Loki Laufeyarson, and they declared him deserving of an ill death, if he could not hit upon a way of losing the wright his wages; and they threatened Loki with violence. But when he became frightened, then he swore oaths, that he would so contrive that the wright should lose his wages, cost him what it might.

"That same evening, when the wright drove out after stone with the stallion Svaðilfari, a mare bounded forth from a certain wood and whinnied to him. The stallion, perceiving what manner of horse this was, straightway became frantic, and snapped the traces asunder, and leaped over to the mare, and she away to the wood, and the wright after, striving to seize the stallion. These horses ran all night, and the wright stopped there that night; and afterward, at day, the work was not done as it had been before. When the wright saw that the work could not be brought to an end, he fell into giant's fury. Now that the Æsir saw surely that the hill-giant was come thither, they did not regard their oaths reverently, but called on Thor, who came as quickly. And straightway the hammer Mjöllnir was raised aloft; he paid the wright's wage, and not with the sun and the moon. Nay, he even denied him dwelling in Jötunheim, and struck but the one first blow, so that his skull was burst into small crumbs, and sent him down below under Niflhel. But Loki had such dealings with Svaðilfari, that somewhat later he gave birth to a foal, which was gray and had eight feet; and this horse is the best among gods and men. So is said in Völuspá:

Then all the Powers strode | to the seats of judgment,

The most holy gods | council held together:

Who had the air all | with evil envenomed,

Or to the Ettin-race | Ódr's maid given.

Broken were oaths then, | bond and swearing,

Pledges all sacred | which passed between them;

Thor alone smote there, | swollen with anger:

He seldom sits still | when such he hears of."

|

|

The giant asks for the sun, the moon and the goddess Freya as his

reward if he completes his task in time —according to the story, within just

one winter. It begs the question, why the sun, the moon and Freya and

why one winter? If we assume the classical association of Freya with

the planet Venus, then the giant wants the sun, the moon and the planet

Venus and it seems clear that the giant’s labors are about astronomy since

he is describing the three brightest objects in the sky.

The giant is building this fortification around Asgard which is the home of

the Aesir. If the 13 Aesir correspond to the constellations of the

zodiac, they are contained within a band that the sun passes through which

we call the ecliptic. The fortification that the giant and his horse

are building is gradually getting higher and higher each day as the horse

pushes the blocks along starting in the winter and ending just 3 days before

the summer. This gradual process seems to be a mythical allusion to

the sun’s apparent movement over time from low down in the heavens in the

winter to high up in the heavens in the summer.

| East |

|

West |

| South

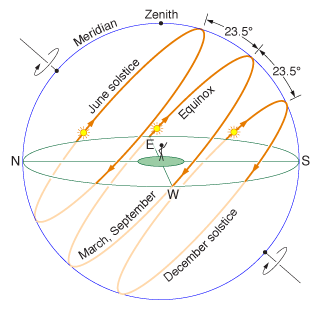

The sun’s apparent path as seen

from the Earth.

|

The sun moves through

our sky in the same way as a star —it rises along the eastern horizon and sets

in the western horizon. Those in mid-northern latitudes always see the noontime

sun somewhere in the southern sky, but, the location of the sun's path across

the sky varies with the seasons. During the Equinoxes, it rises due East and

sets due West.

The sun's path (ecliptic) varies and is farther North during the middle of the

summer and farther south during the winter —this means that the sun is seen

higher in the sky in the summer and lower down in the sky in the winter.

|

The Tropic of Cancer, also referred to as the Northern Tropic, is the most northerly circle of latitude at which the Sun may appear directly overhead at its culmination. This event occurs once per year, at the time of the Northern (summer) solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun to its maximum extent. From the southern to the northern extremes, it almost appears as if a “wall” is being built course by course along the sky from 23.5 degrees North and 23.5 degrees South of the equinoctial line, getting higher and higher until the Summer Solstice when it reaches its peak height.

The word "tropic" comes from the Greek τροπή (trope),

meaning turn (change of direction), referring to the sun appearing to

"turn back" at the solstices. The name “solstice” indicates a

“standing still” since the sun’s apparent motion seems to stop for about

3 days and then it begins to move back in the opposite direction.

As Sir James George Frazer says in the Golden Bough

(pg. 160):

“The Summer solstice or Midsummers Day is the great turning point in the sun’s career, when, after climbing higher and higher day by day in the sky, the luminary stops and thenceforth retraces his steps down the heavenly road.”

European midsummer-related holidays, traditions, and celebrations are pre-Christian in origin. Midsummer's Day (Midsommardagen) in Sweden was formerly celebrated on 24 June which is 3 days past the summer solstice (June 21) and this was (in Sweden at least) understood to traditionally be the first day of summer. Its festivities still include raising a maypole and in former times, the kindling of fires and rolling flaming wheels down hills. In the Finnish midsummer celebration, bonfires (Finnish kokko) are very common and are burned at lakesides and by the sea. In folk magic, midsummer was a very potent night and the time for many small rituals, mostly for young maidens seeking suitors and fertility.

This period of time is connected with many customs about fertility. In Denmark, it is the day where the medieval wise men and women would gather herbs that they needed for the rest of the year to cure people. It has been celebrated since the times of the Vikings by visiting healing water wells and kindling bonfires to ward away the evil spirits.

In Norway, Sankthansaften, as it is now called, is also celebrated with the burning of a large bonfire and in Western Norway, a custom of mock weddings both between adults and between children, apparently meant to symbolize the blossoming of new life, is still kept alive. Such weddings are known to have taken place in the 1800s, but the custom is believed to be older. It is also said that, if a girl puts flowers under her pillow on Midsummer’s night, she will dream of her future husband.

The giant in the story wants to possess Freya (Venus) as part of his reward and fertility is central to the myth we are examining since Svaðilfari and Loki create Sleipnir. The planet Venus is visible as the morning star for 263 days of the year or just about 9 months. This echoes the length of a typical full term human pregnancy and it is likely that because of this the planet Venus came to be associated with the goddess of sexual love in many ancient cultures.

The Sun, the Moon and the planet Venus are all found in the same part of the sky every eight years or 99 months (584 days x 5 = 2920 days, 365 x 8 years = 2920 days and 29.5 x 99 months = 2920.5). After Venus appears as the morning star, it then appears as the evening star for 265 days. This means that a total of 584 earth days pass between the appearance of Venus as the morning star, its disappearance and then its re-appearance as the morning star again. Five of these periods is almost 8 years or 99 lunations and this harkens back to the time period known as the Octaetris, which I have discussed before in a previous essay on Thor and Tyr. Using the planet Venus, in addition to the sun and the moon allows for a greater degree of accuracy in time cycle calculations using the heavenly bodies.

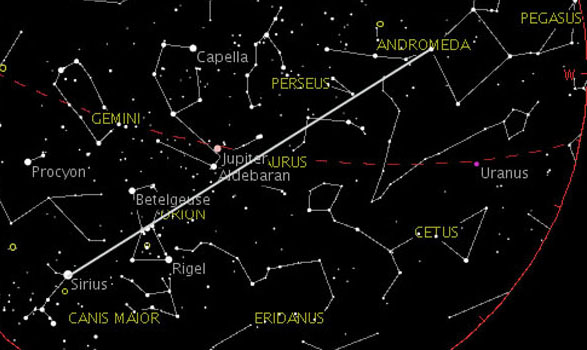

If we take Thor to be Orion, he is found overhead from late autumn to early spring, but in the summer, he is gone. Midsummer occurs in late June and, soon thereafter in July, Pegasus becomes “born” or visible in the sky where it remains visible until January. In a previous essay, I equated the horse Sleipnir with the constellation Pegasus and it would seem that part of the myth is about the summer solstice and the subsequent “birth” of the constellation Pegasus when it becomes visible after the summer solstice.

|

What about Svaðilfari? What does he represent? The name /Sva-ÐIL-fari/ may be etymologically identical with the Vedic god-name Savitr who is likened to a "horse" (Laksman Sarup tr., The Nighantu and the Nirukta. 1920. p. 164, 32nd section, see Wikipedia) and is also a Vedic sun god. His name in Vedic Sanskrit means "impeller, rouser” or “vivifier." It would seem that Svaðilfari is a representation of the sun. Svaðilfari means "unlucky traveler" in Old Norse, and as the sun, he certainly is “traveling” across the sky and the relentless daily “progress” that he makes only to eventually to be lured away before completing the project on time does seem to be a direct reference to the poor luck that the traveling giant experiences because of this horse.

From Winter to the Summer the giant builds the wall higher to stop the encroachment of hrimthursar or frost giants, and this movement of the sun higher and higher into the sky makes the earth warmer and warmer – stopping the hrimthursar in their tracks. Loki can be thought of as a “trickster god” in many cultures seen as a coyote or dog. There is definite evidence linking the Norse god Loki with the star Sirius – the dog star – known in Icelandic as Lokabrenna or “Loki’s burning.”

Sirius’ risings and settings were noted in ancient Chaldean and Babylonian tablets from at least 300 B.C., and Jules Julius Oppert (1825–1905), is reported to have said “that the Babylonian astronomers could not have known certain astronomical periods, which as a matter of fact they did know, if they had not observed Sirius from the island of Zylos in the Persian Gulf on Thursday, the 29th of April, 11542 B.C.!” (R.H. Allen, Star Names from p.120-129 of Star Names by Richard Hinckley Allen, 1889). Certain numbers that are present in Babylonian sources and also in Norse ones suggest transmission of an ancient astronomical tradition to the Norse. Egyptian astronomy and calendars also present many shared elements and it seems that elements of the Egyptian astronomy may have also been part of this tradition – perhaps related to diffusion of agricultural knowledge.

Sirius (“glowing” in Greek) is the brightest star in the sky and is the

only star known with absolute certainty to be found both in Old

Icelandic and in Egyptian records. Its’ Egyptian hieroglyph, a

dog, was found throughout the Nile country and Sirius’ heliacal rising

marked Egypt's New Year.

The heliacal rising of Sirius was used millennia ago to predict the

summer solstice. The day each year that Sirius is first visible in

the pre-dawn sky, known as its heliacal rising, was used in ancient

Egypt to mark the annual cycle of the heavens and the beginning of the

Nile inundation.

The Egyptians devised three calendars: solar, lunar and stellar —all

based on observation of the heavens just like the Norse. They tracked

the lunar cycles and created the lunar calendar of 354 days and measured

the solar calendar at 365 days, but used 360 days for the conventional

year to facilitate sexagesimal calculations, adding 5 epagomenal days at

the end.

Sirius, at the latitude of Thebes in Upper Egypt, would appear just

before dawn at the summer solstice and then within 20 days the Nile

flooding would occur. Sirius became known as the herald of the sun,

announcer of the flood and harbinger of the New Year. The solar year

measured from solstice to solstice is 365.24219 days and the year

measurement based on the heliacal rising of Sirius is 365.25636 days

also known as the Sothic or sidereal calendar. They rounded off

this "tropical year" at the mean between the two measurements settling

on 365 1/4 days. This meant that the 365 day civil calendar used by the

Egyptians diverged in retrograde, recoinciding with the true year every

1460 years, which became known as the Sothic cycle. Adding another 80

years due to the effects of precession and that would have made the

first Sothic Cycle 1540 years and the Egyptian calendar would actually

have begun approximately 4450 BC.

The Egyptian calendar started in the year the summer solstice (June 21) coincided with the helical rising of the Dog Star, Sirius. This was called "the opening of the year." Thus began the first period of the Civil Calendar which fell behind the rising of Sirius by an increasing number of days each century.

The unlucky traveler, or the giant trying to build a wall around Asgard

in one winter, “early in the first days of the gods' dwelling here” is a

personification of the apparent motion of the sun progressing further

northward during the period from the winter solstice to the summer

solstice. The cycles of the sun, the moon, the planet Venus and

the brightest star in the heavens, Sirius, all seem to be described in

this myth.

The trickster, Loki, as Sirius (Lokabrenna), heralds the

approach of the Summer Solstice with its helical rising, and Svaðilfari

is the sun, who is gradually moving higher and higher up in the sky as

the summer approaches, as if he were building a wall up around the

ecliptic, warming the earth. His apparent progress on building the

wall up any higher seems to stop 3 days prior to the beginning of summer

(Midsummers Day).

This was when Svaðilfari stopped helping the giant to build the wall and

instead began to frolic with Loki which later resulted in the birth of

Sleipnir. This would presumably indicate that the constellation Pegasus

becomes visible in the sky in July, soon after the summer solstice.

The 8 legs also seem to reflect the 8 year Octaetris cycle in which the

sun, the moon and Venus are all in the same part of the sky in addition

to Magnússon’s excellent explanation of Sleipnir as the “wind horse.”

Thor isn’t present to start with, but he eventually comes on the scene

as Orion, and when he does, his hammer smashes the giants’ head into

small crumbs.

‘Celtic’ Wheel Symbolism: The Archaeological & Iconographical Evidence For The Links Between Time, Agriculture, & Religious Ideas In The Celtic World From Later Prehistory To The Roman Period. Kevin Jones 2003.