The Cult of Óðinn in Early Scandinavian Aristocracy

by Joshua Rood © 2017

An Excerpt

All Images obtained from the internet. Any copyrights belong to their respective owners.

[TREASURES OF MEDIEVAL ART][HOME][POPULAR RETELLINGS]

| The Iconography of Óðinn | ||||||||||||

|

A number of images appear throughout the corpus of Iron Age Scandinavian physical culture whose features have resulted in researchers comparing them with, or identifying them with Óðinn. Worth particular attention here is a motif-group comprising a number of horned figures (some with one eye), appearing on a variety of mediums, which have long been identified with Óðinn by a number of researchers.143 Mikaela Helmbrecht recently constructed a comprehensive overview of the images as a group, with the conclusion that a connection must exist between these images and the figure of Óðinn (Helmbrecht, 2008, pp. 31-54). The same conclusion was also reached by Neil Price, who has argued that the horned figures with one eye can be placed alongside a variety of other items featuring an altered or damaged eye, including the Sutton Hoo and Valsgärde helmets, all of which, to his mind, also indicate Óðinn worship (N. Price, 2014, pp. 517-538). These images will be the center focus of this study, in which the aim is to focus on the nature, dating and distribution of these items to see whether there is reason to connect them to Óðinn, and if so, whether they add further weight to the evidence given above for the suggestion that the acceptance of Óðinn was related to the acceptance of new forms of rulership in southern Scandinavia. |

||||||||||||

|

6.3.1 Bird-Headed Terminals and

Horned Figures |

||||||||||||

|

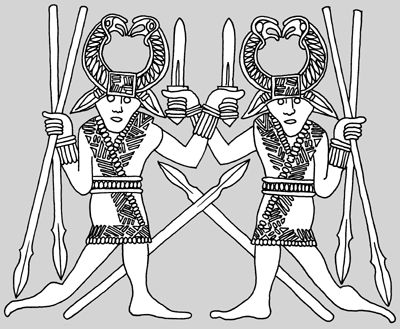

Images of figures wearing some kind of horned headdress are naturally not new (Coles, 2005, pp. 35, 64, 159). In Scandinavia alone, images of this kind appear as early as the Stone Age, and horned costumes were still being used by costumed Nordic guisers in the twentieth century (Gunnell 1995, pp. 98-117). Of course, this does not indicate that all of these images refer to a fixed concept that remained static throughout the several-thousand-year period over which they appear (over and above the fact that they must at some level have a reference to horned animals). On the contrary, as Helmbrecht argues, even if an image of this kind remains formally stable over time, there is a strong likelihood that its meaning for people would have varied in accordance with its immediate context (Helmbrecht, 2008, p. 33). As such, “horned figures” in general are not the main focus here, but rather the specific motif-group noted above, featuring figures in horned, or flat-bowed headdresses, which date to the Vendel era and Viking Age, and are found primarily in southern Scandinavia and eastern Anglo-Saxon England. It is noteworthy that the headdress in question often terminates in bird heads, and that (as Price underlines), the figure occasionally has an intentionally damaged or missing eye. As noted above, Helmbrecht made a case study of the entire motif-group in 2008, using all of those images known to her, although some dozen or so additional figures have since been found (private e-mail from Helmbrecht, dated 2017-03-13). In her research, Helmbrecht makes a careful classification of these images within which she has identified six subgroups, based on dating, context, and the physical attributes of the items in question. She also provides a map, and a chart in which each of the individual objects is numbered, along with details of their find spot, the type of object they are, their iconographic descriptions, their dating, and their find context. Because of the importance of these findings for the present thesis, a brief overview of Helmbrecht’s subgroups will now be provided, along with image examples of each. Following the overview, various particular details will be addressed further. Subgroup 1 (see figures 7 and 8) comprises of eight images, all dating to the Vendel period, which were found primarily in wealthy, warrior graves in eastern Scandinavia, mainly in and around Uppland, as well as in eastern Anglo-Saxon England, from areas known to have been in some contact with southern Scandinavia (see Chapter 5.2). One example comes from Germany. The images appear only on pressed sheet metal, or on a cast-die used for producing pressed sheet metal. They appear on helmets found at Sutton Hoo and Valsgärde (see further below), and on other parts of warrior gear (including a belt buckle). All of them depict “dancing” or running figures, sometimes in pairs (as on figure 8), wielding weapons. In seven of the eight images, the figures are wielding a pair of spears. The “horns” clearly form part of headgear worn by the figures, and in five of the eight images it is noteworthy that these horns end in a pair of bird heads (in one case this is unclear). Only one of the horned figures in this group is depicted as having one eye (that from Torslunda). |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

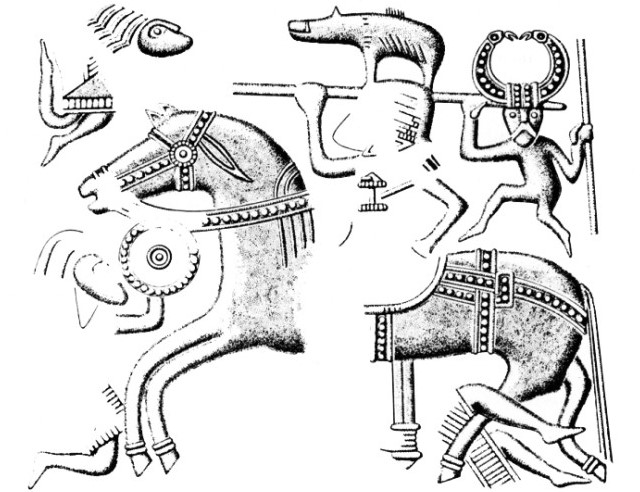

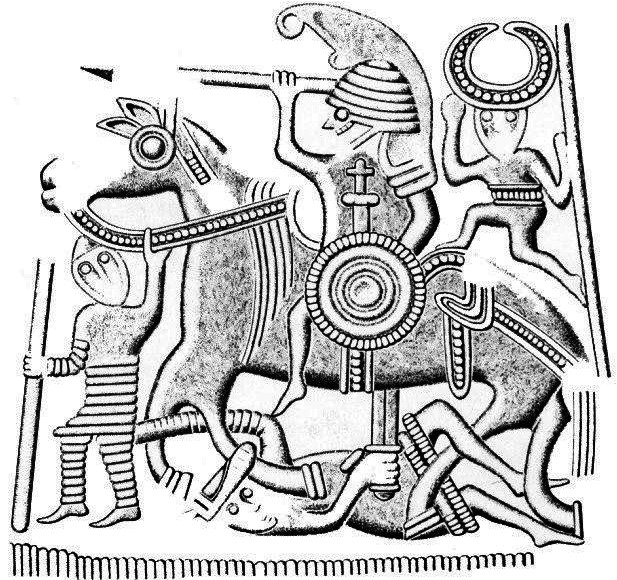

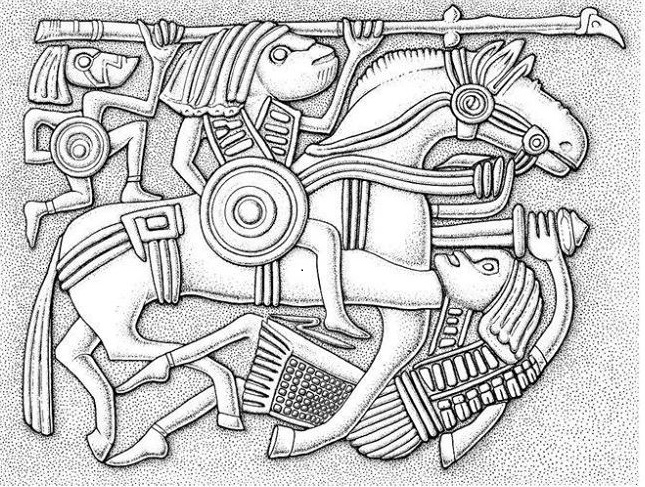

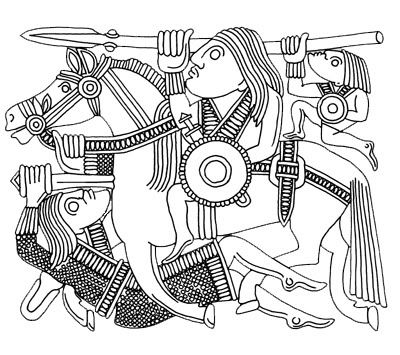

Subgroup 2 (see figures 9 and 10) of the horned figures comprises of only two images, both of which appear on helmets from Valsgärde dated to the seventh century. They depict a mounted warrior, riding into combat, behind which is a small figure, which Helmbrecht describes as a “helping figure”. The figure in question, which seems to be standing on the back of the horse, is holding a spear in one hand and has clear terminals coming out of its head which end in bird heads. Helmbrecht describes the figure as either running or dancing behind the warrior (Helmbrecht, 2008, p. 34). It seems to me, however, that the figure is holding the shaft of the warrior’s spear, as if to guide it. Based on this observation, these “helping figures” can be compared to other, almost identical images, which are found on the Sutton Hoo helmet, and on a gold disc brooch from Pliezhausen, Germany (figures 11 and 12), likewise dated to the early seventh century. 144 |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

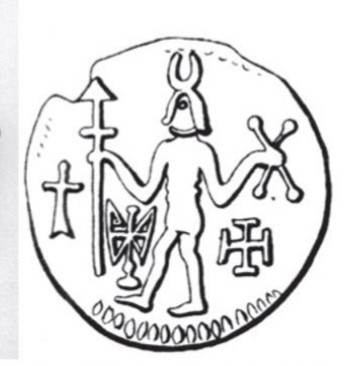

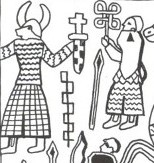

Subgroup 3 (see figures 13

and 14) consists of nine figures, found exclusively in southern

Scandinavia, which appear on one possible brooch, three coins

and two pendants, as well as the Oseberg tapestry from Norway

(three images), all of which are dated to the Viking Age. The

two brooches were found in women’s graves. The same applies to

the Oseberg tapestry which was found in the famous boat grave of

a woman who clearly belonged to the upper milieu of society, and

who possibly had a religious role within her milieu (N. Price,

2002, p. 159). The remaining pieces are stray finds or were

discovered at settlements. Most of these figures seem to be

standing, or walking, and most are carrying a staff or a pair of

baton-shaped objects in one hand (as in figure 14, which offers

obvious parallels to the images in Subgroup 1), and a weapon

such as a sword in the other (in some cases, as in figure 13 it

appears the figure is holding a sword in one hand, and the

sheath to the sword in the other. The horns on the headgear of

these figures either end as points, or as ambiguous knobs that

could perhaps have originally represented birds’ heads.

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Subgroup 4 (see figures 15 and 16) consists of four objects found at settlement sites or stray finds in Scania, and Denmark, which date to the Vendel or early Viking Age, including one found near the hall and cult-house at Tissø, and likewise at Uppåkra. The objects in question are three-dimensional figurines or busts featuring a standing man with large bow-shaped horns, which clearly do not end in animal or bird heads. The shafts of these figures suggest that they were fixed to an object, but it is uncertain what their use was. It is worth noting that two of the objects seem to have once been holding something. Only one of the figures from this group, the figure from Uppåkra, is depicted as having one eye (see below and figure 15). |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Subgroup 5 (see figure 17) is comprised of five objects which

are very similar to those in Subgroup 4. The objects in question

take the form of busts of the head and sometimes upper torso of

a male figure, and appear to have been fixed onto another

object. Unlike the figures in Subgroup 4, however, the horns on

these figures end in clear, even elaborate bird heads (much like

those in Subgroups 1 and 6), the ends of which touch to form a

complete ring. One of the objects from this group again is

one-eyed (from Staraja Ladoga). The objects in question are all

from the Vendel era and Viking Age, their dates ranging from the

seventh century through to the ninth. They are found in southern

Scandinavia, eastern England, and Russia (at Staraja Ladoga, a

Scandinavian settlement: see further below), three of them in

graves (one belonging to a woman), while the other two come from

settlement sites. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

The final Subgroup 6 (see figure 18) is comprised of five objects representing a style of head that diverges somewhat from those so far mentioned. According to Helmsbrecht, these figures probably belong to a different motif, that of a “head with two flanking animals”, which finds similarities throughout Scandinavia and Slavic regions (Helmsbrecht, 2008, p. 39). Two of the figures in question were found in graves (one belonging to a woman), while another one was found at a settlement site. Two were isolated finds. All of the objects were found in Southern and central Sweden and Denmark, and date primarily to the Vendel period, although some come from the early Viking Age. The objects all consist of a human head flanked by two downturned birds’ heads. As noted above, it is clear that only three of the horned-figures described above are one-eyed (those from Torslunda, Uppåkra, and Staraja Ladoga), although Helmsbrecht mentions a further one-eyed, horned figure that will be discussed further below. As noted above, recent research by Neil Price has demonstrated that the motif of the “One Eye” needs to be considered in a wider context, since the motifs extend beyond the horned figures themselves. They are also found on other images connected to the same kind of warrior gear as that associated with many of the horned figures, including eye-guards found on the headgear worn by aristocratic warriors, as will be seen in connection with the Sutton Hoo helmet discussed further below (N. Price, 2014, pp. 517-538).145 |

||||||||||||

| 6.3.2 One-Eyed Figures | ||||||||||||

| 6.3.2.a One-Eyed Figures with Horns or Birds’ Heads | ||||||||||||

|

For obvious reasons, not least relating to the fact that

in medieval Icelandic literature Óðinn is often described as

having one eye,146

it is logical to focus a little more closely on those horned

figures mentioned above which also have only one eye. These

appear in the following contexts: |

||||||||||||

|

The Torslunda Dancer

(sixth-eighth century):147

This image appears on part of a sheet metal stamping matrix

found from Torslunda, on the Swedish island of Öland. It is

worth noting that the scene depicts a dancing, horned figure

beside a second figure dressed in a wolf costume, the horns on

the horned figure’s head ending once again in two birds’ heads.

Using laser-scanning, scholars from the Archaeological Research

Laboratory in Stockholm have conclusively demonstrated that the

figure’s right eye has been struck out with a squaretipped

object, probably a chisel (see Arrhenius and Freij, 1992, pp.

76-81). What this means is that the image was originally

manufactured with both eyes, and that someone intentionally

stabbed out an eye after this occurred. The Staraja Ladoga Horned Figure (eighth-ninth century).148 This bronze figure which was probably designed to go on the end of a handle to an unknown object was found among a hoard of smith’s tools at a Scandinavian settlement from Staraja Ladoga, in Russia, and has been dated to between 750 and 800. The handle represents a man’s head, crowned with horns which terminate in bird’s heads (Roesdahl and Wilson, 1992, p. 298). Its left eye had clearly been struck out with a sharp object (Price, 2014, p. 525). |

||||||||||||

Torslunda Bronze helmet plate |

||||||||||||

| The Uppåkra Horned Figure (eighth-tenth century).149 This horned figure was found at Uppåkra, not far from the eyebrow ridge mentioned in Chapter 5.4.1 and discussed further below. The figurine in question has been dated to the ninth century and represents a standing man with horned terminals rising from his head. As noted above, since the horns are broken, it is unknown if they terminated in bird’s heads or not. In this case, the figures’ right eye has been depressed into a concave hole, while the left eye remained convex after its manufacturing (Bergqvist, 1999, pp. 119-21; Helmbrecht, 2008, pp. 35-43). | ||||||||||||

|

The

Ribe Horned Pendant (eighth-tenth century). This small pendant

was found at Ribe in Denmark, the same market settlement in

which the skull fragment with the Óðinnic runicinscription noted

in Chapter 6.1 was found. The pendant is of a male head with a

moustache and horned headgear. Here, the right eye is marred

with a clear punch-mark from a sharp object. As with the others,

this clearly occurred after the object was manufactured

(Helmbrecht, 2008, p. 43). |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| 6.3.2.b One-Eyed Figures Without Horns | ||||||||||||

|

As noted above, Price and others

have suggested that several other one-eyed figures should be

considered alongside those which have horned headdresses, so

these will also be noted here: The Valsgärde Helmet 7 Animal-Crest (seventh-eighth century). It is worth noting that the helmet found in Valsgärde burial 7 features a prominent crest which terminates in an animal head just over the brow of the face-guard. The animal’s eyes are made from garnet. While the right eye is made of a light garnet and backed with gold-foil, the left eye was made with a dark garnet, and is not backed with a foil (a pattern which was repeated elsewhere: see below). The effect of the missing foil behind the garnet, and the use of a darker garnet, is that it causes one of the beast’s eyes to shine much brighter than the other. The difference between the two eyes is stark and obvious, and, as will be discussed further below, must have been an intentional stylistic effect (see figure 20). |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| The Vendel Grave 12 Animal-Grip (seventh century). Among the finds at the boat burial at Vendel grave 12 was a shield, the grip of which terminates in an animal head. It is interesting to note that the animal head was given identical treatment to the one on the helmet crest from Valsgärde. In other words, the left eye is not backed with a gold foil, while the right eye is. | ||||||||||||

| The Sutton Hoo Helmet Animal-Crest (seventh century). The Sutton Hoo helmet features a crest ending in an animal head, on which the garnet which forms the left eye lacks a foil backing, much like that from Valsgärde (see above). | ||||||||||||

| The Elsfleth Buckle Mask (late sixth century). Here, the silver-gilt tongue to a buckle found at Elsfleth, in north-west Germany, is decorated with a mask-like face, on which gouge marks are clearly visible, leaving a jagged hole where the left eye had once been. The buckle belongs to a group of equipment found in warrior graves, such as Sutton Hoo (N. Price, 2014, p. 525). | ||||||||||||

|

The

Lindby Figurine (seventh century). This is a small figurine of a

standing man with a moustache and conical hat, found at Lindby,

in Scania. Here, the figure’s right eye is depicted as a simple

line, as if closed, while the left eye is “open” (Abram, 2011,

p. 8). |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| 6.3.2.c The One-Eyed Masks | ||||||||||||

|

Perhaps most interesting of

all in the present context is that evidence also exists of

Iron-Age rulers or prominent aristocratic figures giving special

attention to one eye on the facemask of their own ceremonial

headgear. Either the masks of their helms would have been

manufactured to give the impression that the wearer was

one-eyed, or else altered as a means of emphasizing an eye.

There is also evidence to suggest that rulers could have

ritually deposited one of the oculars or eye-guards of their

helm. These items add weight to the idea that the images

discussed above (and especially those with a ritual context like

the Torslunda helmet die and the processional images on the

Oseberg tapestry) might depict a ruler utilizing the concept of

being one-eyed in a ritualistic setting. In the very least, the

implication is that the images represent a concept that could

that on occasion be embodied by living, breathing members of

society. The Sutton Hoo Helm (early seventh century) (see figure 23). The main item in this group is the famous, mask-like ceremonial helmet found at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, England, which came from a royal burial complex comprising of several mounds, one of which contained a ship-burial, dating to sometime around 625 (Bruce-Mitford, 1974, p. 24). The individual buried in the ship was undoubtedly a ruler. The nature of the artifacts, and not least the style of the helm and the plates, which, as noted above in Chapter 5.2.6 have close parallels to those found at Valsgärde, Vendel, and Torslunda in Sweden, make it clear that the figure in question belonged to the same elite milieu as that discussed in Chapters 5.2-5.4, which was taking an ever-increasing role in the Germanic world in the Age of Migrations, and particularly in southern Scandinavia.150 |

||||||||||||

Figure 23. The Sutton Hoo Helmet British Museum |

||||||||||||

| The Sutton Hoo helm was made of sheet-iron with a neck guard, cheek guards, and a facemask. A prominent crest terminating in animal heads runs the crown of the helm from back to front, and part of the facemask is decorated with a flying animal or dragon. The body of the animal forms the nose of the mask, while its wings and tail form the brow ridges and moustache.151 The surface of the helm is covered with bronze plates like those also found on many of the Vendel and Valsgärde helms, which are decorated with elaborate patterns and symbolic scenes of figures dancing or fighting. Many of the panels on the Sutton Hoo helm are badly damaged, and only some of the images are recoverable. One of the panels in question already discussed above as belonging to Subgroup 1, depicts a pair of dancing figures wearing horned headgear terminating in pairs of birds’ heads (figure 8). A second panel from the helmet, also mentioned above in relation to Subgroup 2, depicts a riding warrior holding a spear with a second, small figure “guiding” the spear from behind (figure 12; see also Bruce-Mitford, 1974, pp. 13, 14, 198-213). | ||||||||||||

| Bearing in mind that fact that the helmet plates seem to make reference to Óðinnic figures, it is interesting to note that both of the eye openings of the mask are lined with garnets, and that that the garnets lining the left eye are curiously missing the gold-foil backings which are used on the right eye of the helm. As has been noted from an early point, this is particularly curious in the light of the fact that foil backings for garnets are found in almost all of the other garnet finds in the entire expansive Sutton Hoo collection (with one exception: see below) (see Bruce-Mitford, 1978, p. 169; and Marzinzik, 2007, pp. 29-30). There was obvious reason to consider further what the reason for the lack of gold foil behind the garnets of the left eye might be. As most scholars agree, the purpose of gold or silver backings behind garnets was to reflect light through the garnet and to allow the gem to shine brightly.152 Without gold backings, the garnets lining the left eye would have appeared dark and lusterless compared to those lining the right eye (not least in firelight). Indeed, when Price and Paul Mortimer tested a reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helm, both outdoors in bright sunlight, and particularly within the firelight of reconstructed halls, they found that the eyes were starkly contrasted. According to Price, from his observation within the dim light of a hall, the mask appeared to be one-eyed, not least because in the darkness the real eyes of the wearer were not visible (Price, 2014, 522). In this context, it is also worth bearing in mind that the same approach was taken with the left eye of the animal crest on the helm. There is logical reason to consider a potential connection between such a helm and the objects that will be considered next. | ||||||||||||

| Deposited Eye-Guards (see figures 21 and 22). As has been mentioned in Chapter 5.4.1, just outside of the cult-house at Uppåkra, a highly decorative eye-ridge was discovered which could well have belonged to a helmet very much like those from Sutton Hoo, Valsgärde, and Vendel. The eye-guard in question has been dated, as with the others, to the Vendel period (Helgesson 223). Given the location of the find, just south of the cult-house, and the spears and other military equipment ritually deposited nearby, Price has argued that this eye-ridge must have been taken off a helmet also been ritually deposited (Price, 2014, p. 523). | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

It is noteworthy that the

deposited eye-ridge has a parallel found at Gevninge, just north

of Lejre in Denmark. Here, a metal detector discovered an entire

right ocular ring, with a sculpted brow, which would have

belonged to a helm much like the others discussed above. Like

those noted above, it is dated to the Merovingian period. Based

on the find context Christensen has similarly argued, based on

the find context, that the ocular was ritually deposited

(Christensen, 2002, p. 43).153

|

||||||||||||

| Footnotes | ||||||||||||

|

143 The amount of literature that has come about as a result of attempts to identify Óðinn in Iron Age imagery is too large to detail here. Some individual images appearing in the late Viking Age could be argued to depict Óðinn, the fact that they are often dated to a point which is later than this thesis regards, and due to the fact that they often do not fall into a motif-group which can give insight, they will not be regarded here. Perhaps the best example of a probable Óðinn figure which will disregarded in this case study, is the enthroned figure flanked by two birds, mentioned in a footnote in Chapter 5.3.4. Other images which have frequently been identified as Óðinn, but are much less convincing. One such image is the figure of a figure riding an “eight-legged horse” on the Alskog Tjängvide I and Ardre Kyrka VIII picture stones on Gotland (Hejdström, 2012, p. 20) In short, the horse could be running, and as Helmbrecht writes, “a drinking horn does not make a valkyrie, a spear does not make Odin – these attributes may just mark the figures as male or female” (Helmbrecht, 2012, p. 86) Various bracteates have tentatively been interpreted as representing Óðinn over the years and also deserve mention because of their frequent mention here, and because of the impact the research on them has had. Karl Hauck, the most prominent scholar to make such arguments, in fact went as far as arguing that most of the images on the Type A, B and C bracteates (for a review of these types, see Hauck, 1986, pp. 474-512) were representative of Óðinn. In his attempt to construct a coherent interpretive system out of the bracteate iconography, Hauck argued that the Type C bracteates, in particular, were pictorial equivalents to the myth related in the Second Merseburg Charm (see footnote in Chapter 5 above), and showed Óðinn healing the injured leg of a horse (Hauck, 1986, p. 487; 1998, p. 39). In the last twenty years, however, Hauck’s arguments for the figure on the bracteates representing Óðinn have faced considerable criticism. A comprehensive overview of Hauck’s research and of the criticism it has faced is provided by Nancy Wicker (2014, pp. 25-26). As Wicker shows, Hauck’s identifications are too problematic to be relied upon. If we disregard Hauck´s systemic interpretations of the bracteates as depicting Óðinn, they become a heterogenous collection of items that depict a wide variety of images and image types (Wicker, 2014, p. 26). There is thus no trustworthy means of including the bracteate iconography in this review of Óðinnic iconography. |

||||||||||||

| 144 Both the Sutton Hoo helmet and the Pliezhausen disc contain an almost identical scene to that portrayed on the Valsgärde helmets: a rider on a horse is trampling a fallen man. The warrior’s spear is hoisted, and behind the rider is a little figure, posed like the helping figures from Valsgärde, which has one hand on the rider’s spear. It should be stressed however, that the helping figures from both Pliezhausen and Sutton Hoo lack the horned helmet, and are holding a buckler or shield in place of their own spear (see figures 11 and 12 | ||||||||||||

| 145 Unless otherwise referenced, I am basing my overview here on Neil Price’s own investigation into the “OneEye” motif: see N. Price, 2014, pp. 517-538. | ||||||||||||

|

146 See, for example,

Gylfagynning, p. 17; Skaldskaparmál, p. 8; Vǫluspá, st. 28;

Vǫlsunga saga, p. 28. 147 This is the one-eyed figure mentioned in Subgroup 1 above. See figures 7 and 19. 148 This is the one-eyed figure mentioned in Subgroup 5 above. See figure 17. 149 This is the one-eyed figure mentioned in Subgroup 4 above. See figure 15. |

||||||||||||

| 150 There are so many similarities between the weapons and equipment found at Sutton Hoo and that found in sites like Valsgärde and Vendel (including the phenomena of the ship burial itself), that scholars have regularly debated whether the items found, and not least the ruler himself might have originated in Scandinavia rather than England. See further Bruce-Mitford, 1974, pp. 1-60; and Arwidsson, 1983, pp. 71-82 | ||||||||||||

| 151 The process of designing the nose and brow guards to look like an animal is once again not unique to Sutton Hoo. It also appears on the Vendel grave 14 helmet (Bruce-Mitford, 1974, plate 55; and Arrhenius & Freij, 1992, pp. 75-110). | ||||||||||||

| 152 Price sums up the importance of cloisonne-technique garnet-work as follows:: “Although garnets can be quite bright, especially if cut thinly, when placed in this way against a solid background their lustre is substantially dimmed. Early medieval jewel-smiths solved this problem by inserting wafer-thin foils of gold, or occasionally silver, at the base of the cells into which the garnets were set. Stamped with a cross-hatched pattern, the foils reflected light back through the stone to produce the gorgeous red glow for which the Sutton Hoo regalia is known. The use of gold foils in this way is virtually universal in Anglo-Saxon and Merovingian cloisonné garnet jewelry, and Sutton Hoo is no exception” (N. Price, 2014, p. 521). | ||||||||||||

| 153 Also deserving mention in this context is a bronze facemask from the Roman iron Age, found within a house foundation at Hellvi on the Swedish island of Gotland. This facemask was originally a Roman cavalry parade helmet apparently representing Alexander the Great (the second Roman parade helmet to be found in Scandinavia). The mask seems to have been deposited in the middle of the sixth century, a few hundred years after its creation. What makes it both unique and relevant in the present context is that at some point the original eyes of the mask were removed and replaced with new ones made of polished bronze and silver. These new eyes are unlikely to be Roman work, and are believed to have been manufactured by Swedish smiths. According to Price, the result would have been that the antique mask would have had piercing, gold and silver colored eyes (N. Price, 2014, p. 527). Of most interest here is that one of the eyes was missing from the mask when it was found, although it was later found in a later excavation in the same house. According to Price it, is likely that the mask hung from the roof-bearing pillar, and that one of its eyes was ritually removed and buried in the floor below. The Hellvi mask is particularly interesting because it is yet another example of Scandinavians emulating Romans, in a local context (see also Chapters 5.2.5-5.2.6). |

[TREASURES OF MEDIEVAL ART][HOME][POPULAR RETELLINGS]