The Complete

Fornaldarsögur Norðurlanda

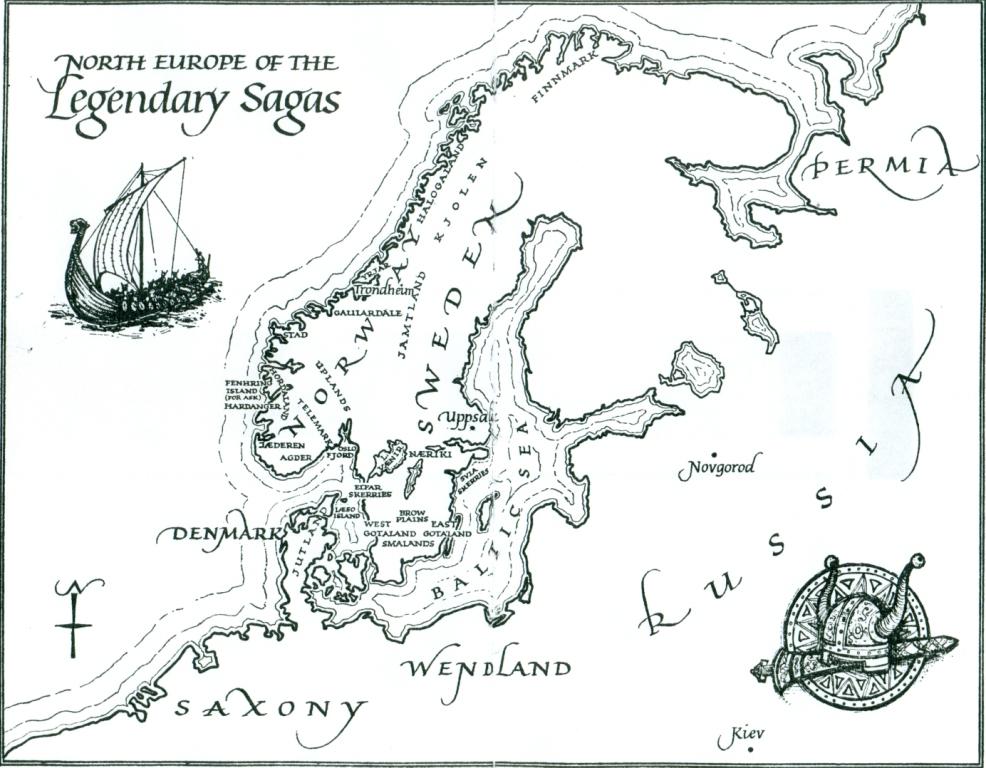

Legendary Sagas of the Northland

in English Translation

"King Gudmund of the Glittering Plains"

Who is Guðmund of Glæsisvellir?

King Guðmund appears in several of the fornaldarsögur. In the legend of Helgi Thorisson, he is pitted against the Christian King Olaf Tryggvason as a representative of the new and true doctrine. King Gudmund of the Glittering Plains represents the older heathen doctrine. The author would not have done this if he had not believed that the king of the Glittering Plains had his ancestry in heathendom.

From Vikings in Russia by Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards,

1989.

Is

Gudmund and his realm an invention of Christian times or is

any person found in the mythology who dwells in a similar environment and is

endowed with similar attributes and qualities?

Upon reflection, these qualities also describe Mimir, perhaps the

most characteristic figure of all Germanic mythology. He is the lord of the fountain which bears

his name. Odin covets its liquid, yet he has neither authority nor power over it.

Neither he nor anyone else of the gods seek to get control of it, even upon Mimir's

death. His authority remains unchallenged. To get a drink from it, Odin must subject

himself to great sufferings and sacrifices (Völuspá

27-28; Hávamál 138-140; Gylfaginning

15), and it is as a gift or a loan that he afterwards receives from

Mimir the invigorating and soul-inspiring drink (Hávamál

140-141). Over the fountain and its territory Mimir, exercises unlimited control, an authority which the gods never appear to

have disputed. He has a sphere of power which the gods recognize as

inviolable. The domain of his rule belongs to the lower world; it is

situated under one of the roots of the world-tree (Völuspá

27-28; Gylfaginning 15), and

when Odin, from the world-tree, asks for the precious mead of the

fountain, he peers downward into the deep, and from there brings up the

runes (nýsta eg niður, nam eg up rúnar -

Hávamál 139). Saxo's account of the adventure of Hotherus (Hist., Book 3) shows that there was thought to be a descent to

Mimir's land in the form of a mountain cave (specus), and that this descent was, like the one to Gudmund's

domain, to be found in the uttermost North, where terrible cold reigns.

Like Gudmund of Glæasisvellir, Mimir is the collector of treasures. According to mythology, the same treasures that Gorm and his men find in the land which Gudmund lets them visit are in the care of Mimir: the wonderful horn (Völuspá 27), the sword of victory, and the ring (Saxo, Hist., Book 3).

Líf og

Leifþrasir,

en þau leynast

munu

í holti

Hoddmímis.

Morgundöggvar

þau sér að mat

hafa,

en þaðan af aldir alast.

Lif and Leifthrasir

are concealed

in Hodd-Mimir's grove.

Morning dews

they will have for nourishment,

From them are born (new) races.

Lif and Leifthrasir must have had their secure place of refuge in Mimir's grove

during the fimbul-winter, which

precedes Ragnarok. And, accordingly, the idea that they were there only during

Ragnarok is unfounded. They

continue to remain there while the winter rages, and during all the episodes

which characterize the progress of the world towards ruin, and, finally, also,

as Gylfaginning reports, during the

conflagration and regeneration of the world.

Still the purpose of

Mimir's land is not limited to being a protection for the

fathers of the future world against moral and physical

corruption, through this epoch of the world, and a seminary

where Baldur educates them in virtue and piety. The grove

protects, as we have seen, the

ásmegir during

Ragnarok, whose flames do not penetrate therein. Thus the grove,

and the land in which it is situated, exist after the flames of

Ragnarok are extinguished. Was it thought that the grove after

the regeneration was to continue in the lower world and there

stand uninhabited, abandoned, desolate, and without a purpose in

the future existence of gods, men, and things?

The last moments of the existence of the crust of the old earth

are described as a chaotic condition in which all elements are

confused with each other. The sea rises, overflows the earth

sinking beneath its billows, and the crests of its waves aspire

to heaven itself (cp.

Völuspá 58:2 - sígur fold í mar, with Völuspá

in skamma 14:1-3 - Haf

gengur hríðum við himin sjálfan, líður lönd yfir). The

atmosphere, usurped by the sea, disappears, as it were (loft

bilar - Völuspá in

skamma 14:4). Its snow and winds (Völuspá

in skamma 14:5-6 -

snjóar og snarir vindar) are blended with water and fire,

and form with them heated vapors, which "play" against the vault

of heaven (Völuspá

58:7-8 - leikur hár hiti

við himin sjálfan). One of the reasons why the fancy has

made all the forces and elements of nature thus contend and

blend was doubtless to furnish a sufficiently good cause for the

dissolution and disappearance of the burnt crust of the earth.

At all events, the earth is gone when the rage of the elements

is subdued, and thus it is not impediment to the act of

regeneration which takes its beginning beneath the waves.

This act of regeneration consists in the rising from the depths

of the sea of a new earth, which on its very rising possesses

living beings and is clothed in green. The fact that it, while

yet below the sea, could be a home for beings which need air in

order to breathe and exist, is not necessarily to be regarded as

a miracle in mythology. Our ancestors only needed to have seen

an air-bubble rise to the surface of the water in order to draw

the conclusion that air can be found under the water without

mixing with it, but with the power of pushing water away while

it rises to the surface. Like the old earth , the earth rising

from the sea has the necessary atmosphere around it. Under all

circumstances, the seeress in

Völuspá 60 sees after

Ragnarok -

|

...upp

koma

öðru sinni

jörð úr ægi

iðja græna. |

…come up

a second time

earth out of the sea iðja green. |

The earth risen from the deep has mountains and cascades, which,

from their fountains in the fells, hasten to the sea. The

waterfalls contain fishes, and above them soars the eagle

seeking its prey (Völuspá

60:5-8). The eagle cannot be a survivor of the beings of the

old earth. It cannot have endured in an atmosphere full of fire

and steam, nor is there any reason why the mythology should

spare the eagle among all the creatures of the old earth. It is,

therefore, of the same origin as the mountains, the cascades,

and the imperishable vegetation which suddenly came to the

surface. The earth risen from the sea also contains human

beings, namely, Lif and Leifthrasir, and their offspring.

Mythology did not need to have recourse to any hocus-pocus to

get them there. The earth risen from the sea had been the lower

world before it came out of the deep, and a paradise-region in

the lower world had for centuries been the abode of Lif and

Leifthrasir. It is more than unnecessary to imagine that the

lower world with this Paradise was duplicated by another with a

similar

Among the mountains which rise on the new earth are found those

which are called Niða

fjöll (Völuspá

67), Nidi's mountains. The very name

Niði suggests the

lower world. It means the "lower one." Among the abodes of

Hades, mentioned in

Völuspá, there is also a hall of gold on Nidi's plains (á

Niða völlum - Völuspá

37), and from Sólarljóð

(56) we learn - a statement confirmed by much older records -

that Nidi is identical with Mimir. Thus, Nidi's mountains are

situated on Mimir's fields.

Völuspá's seeress

discovers on the rejuvenated earth Nidhogg, the corpse-eating

demon of the lower world, flying, with dead bodies under his

wings, away from the rocks, where he from time immemorial had

had his abode, and from which he carried his prey to Nastrond (Völuspá

38-39). There are no more dead bodies to be had for him, and his

task is done. Völuspá's

description of the regenerated earth under all circumstances

shows that Nidhogg has nothing there to do but to fly thence and

disappear. The existence of Nidi's mountains on the new earth

confirms the fact that it is identical with Mimir's former lower

world, and that Lif and Leifthrasir did not need to move from

one world to another in order to get to the daylight of their

final destination.

In their youth, free from care, the Aesir played with a wonderful tafl game. But they had it only í árdaga, in the earliest time (Völuspá 8, 61). Afterwards, they must in some way or other have lost it. The Icelandic sagas of the Middle Ages have remembered this tafl game, and there we learn, partly that its wonderful character consisted in the fact that it could itself take part in the game and move the pieces, and partly that it was preserved in the lower world, and that Gudmund-Mimir was in the habit of playing tafl (Fornaldarsögur: Saga Heiðreks konungs ins vitra ch. 6; Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks konungs ch. 5; Sörla saga sterka ch. 4; Egils saga einhenda ok Ásmundar berserkjabana chs. 12, 13, 15; In the last passages, the game is mentioned in connection with another subterranean treasure, the horn.) If, now, the mythology had no special reason for bringing the tafl game from the lower world before Ragnarok, then they naturally should be found on the risen earth, if the latter was Mimir's domain before. Völuspá 61 also relates that they were found in its grass:

Þar munu

eftir

undursamlegar

gullnar

töflur

í grasi finnast.

There, once again, will

the wonderous

golden tablemen

be found in the grass.

Thus, when the Fornaldarsagas speak of Guðmund and his realm, they provide us additional insight into Mimir and his role in Germanic mythology:

5. Now Thorsteinn saw three well armed men riding, and so huge that he had never seen such large men before. The one who rode in the middle was the largest, in clothes woven through with gold, on a pale horse, and the two others rode on gray horses in red scarlet clothes.

...The biggest man took a gold ring from his finger and gave it to Thorsteinn. It was three aura in weight. Thorsteinn said: "What is your name, and from what background are you, and into what land have I come?"

"Godmund is my name. I rule that place which is called Glaesir Plain. They are a colony of that land that is called Risaland. I am a king’s son, and my squires are called Fullsterk and Allsterk. But did you see any men ride here this morning.?"

Thorsteinn said: "Twenty-two men rode here and did not slow down."

"They are my squires," said Godmund. "That land lies nearby, called Giant-land. A king rules there, who is called Geirrod. We are tributaries under him. My father was called Ulfheidinn the Trustworthy. He was called Godmund, like everyone else who lives in Glaesir Plain. But my father went to Geirrod’s court to deliver his tribute to the king, and died on the journey. The king gave me a request that I should have a funeral feast for my father, and take the rank that my father had. But we are not happy to serve the Giants."

"Why do your men ride ahead?" said Thorsteinn.

"A great river divides our land," said Godmund. "It is called Hemra. It is so deep and strong, that no horses can ford it, except those which we companions ride. Those others have to ride to the source of the river, and we meet in the evening."

...They now rode to the river. There was a house there, and they took other clothes, and dressed themselves and their horses. The clothes were of such a nature that water could not touch them, but the water was so cold that gangrene would set in, if anything got wet. They then forded the river. The horses pushed ahead strongly. Godmund’s horse stumbled, and Thorsteinn got water on his toe, and gangrene then set in. When they came out of the river, they spread out their clothes to dry. Thorsteinn cut off his toe, and they were very impressed with his valor. They then rode on their way.

...They now came to the town, and Godmund’s men came to meet them. They now rode into the town. They could now hear all kinds of instruments, but Thorsteinn did not think much of the tune. King Geirrod came now toward them and greeted them well, and they were shown a stone house or hall to sleep in and men to lead their horses to the stalls. Godmund was led to the king’s hall. The king sat on the high seat, and his earl next to him, who was called Agdi. He ruled the district that was called Grundir. That is between Risaland and Giant-land. He had his residence at Gnipalundi. He was a sorcerer and his men were more like trolls than men.

Godmund sat on a step before the high seat opposite the king. It was

their custom that the king’s son should not sit at the high seat, before

he took title from his father and had drunk the first toast. A fine

feast got under way, and men drank and were merry and then went to

sleep.

7. The king who ruled there was named Harek. He was married, and had two sons. One was named Hraerek and the other Siggeirr. They were great champions, and retainers of King Gudmund of Glaesir Plain, and were his land guardians. The king's daughter was named Edda. She was pretty to look at, and very capable in most matters.

8. "Here in the forest stands a great temple. King Harek owns it, who rules here over Bjarmaland. The god called Jomali is worshipped. There is much gold and treasure. The king's mother, who is called Kolfrosta, is in charge of the temple. She is made strong by witchcraft so that nothing takes her by surprise. She knows beforehand with her magic that she will not live out this month, and so she traveled in the shape of an animal east to Glaesir Plain and took away Hleidi, the sister of King Gudmund, and intends that she shall be one of her priestesses. That is a loss indeed, for she is the most beautiful and most courteous maiden, and it would be best if that could be prevented."

Related Sagas & Concepts:

Other Sources:

Samsons Saga Fagra

['Saga of

Samson the Fair']:

A later saga which

places Gudmund’s realm in

The oldest source for the legend of

Guðmund of Glæsisvellir is Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Dancorum,

Book 8, written around 1200, which predates the Icelandic

fornaldarsögur by one or two centuries, and Snorri Sturluson's

Edda by about a generation. Here Glæsisvellir is part of the

underworld :

|

Dan 8.14.6 (p. 240,4)

1 Quo

facto, optato vento excepti in ulteriorem Byarmiam navigant.

2 Regio

est perpetui frigoris capax praealtisque offusa nivibus, ne vim

quidem fervoris persentiscit aestivi, inviorum abundans nemorum,

frugum haud ferax inusitatisque alibi bestiis frequens.

3 Crebri

in ea fluvii ob insitas alveis cautes stridulo spumantique

volumine perferuntur.

4 Illic

Thorkillus, subductis navibus, tendi in litore iubet, eo loci

perventum astruens, unde brevis ad Geruthum transitus foret.

5 Prohibuit

etiam ullum cum supervenientibus miscere sermonem, affirmans

monstra nullo magis nocendi vim quam advenarum verbis parum

comiter editis sumere, ideoque socios silentio tutiores

exsistere; se vero solum tuto profari posse, qui prius gentis

eius mores habitumque perviderit. |

This done, a favouring wind took them, and they sailed to

further Permland. It is a region of eternal cold, covered with

very deep snows, and not sensible to the force even of the

summer heats; full of pathless forests, not fertile in grain and

haunted by beasts uncommon elsewhere. Its many rivers pour

onwards in a hissing, foaming flood, because of the reefs

imbedded in their channels. Here Thorkill drew up his ships

ashore, and bade them pitch their tents on the beach, declaring

that they had come to a spot whence the passage to Geirrod would

be short. Moreover, he forbade them to exchange any speech with

those that came up to them, declaring that nothing enabled the

monsters to injure strangers so much as uncivil words on their

part: it would be therefore safer for his companions to keep

silence; none but he, who had seen all the manners and customs

of this nation before, could speak safely. |

|

Dan 8.14.7 (p. 240,14)

1 Crepusculo

appetente, inusitatae magnitudinis vir, nominatim salutatis

nauticis, intervenit.

2 Stupentibus

cunctis, Thorkillus adventum eius alacriter excipiendum

admonuit, Guthmundum hunc esse docens, Geruthi fratrem,

cunctorum illic applicantium piissimum inter pericula

protectorem.

3 Percontantique,

quid ita ceteri silentium colerent, refert rudes admodum linguae

eius ignoti pudere sermonis.

4 Tum

Guthmundus hospitio invitatos curriculis excipit.

5 Procedentibus

amnis aureo ponte permeabilis cernitur.

6 Cuius

transeundi cupidos a proposito revocavit, docens eo alveo humana

a monstruosis secrevisse naturam nec mortalibus ultra fas esse

vestigiis. |

As

twilight approached, a man of extraordinary bigness greeted the

sailors by their names, and came among them. All were aghast,

but Thorkill told them to greet his arrival cheerfully, telling

them that this was Gudmund, the brother of Geirrod, and the most

faithful guardian in perils of all men who landed in that spot.

When the man asked why all the rest thus kept silence, he

answered that they were very unskilled in his language, and were

ashamed to use a speech they did not know. Then Gudmund invited

them to be his guests, and took them up in carriages. As they

went forward, they saw a river which could be crossed by a

bridge of gold. They wished to go over it, but Gudmund

restrained them, telling them that by this channel nature had

divided the world of men from the world of monsters, and that no

mortal track might go further. |

|

Dan 8.14.8 (p. 240,23)

1 Subinde

ad ipsa ductoris penetralia pervenitur.

2 Illic

Thorkillus, seductis copiis, hortari coepit, ut inter

tentamentorum genera, quae varius obtulisset eventus, industrios

viros agerent atque a peregrinis sibi dapibus temperantes

propriis corpora sustentanda curarent discretasque ab indigenis

sedes peterent, eorum neminem discubitu contingendo.

3 Fore

enim illius escae participibus inter horridos monstrorum greges,

amissa cunctorum memoria, sordida semper communione degendum.

4 Nec

minus ministris eorum ac populis abstinendum edocuit. |

Then they reached the dwelling of their guide; and here Thorkill

took his companions apart and warned them to behave like men of

good counsel amidst the divers temptations chance might throw in

their way; to abstain from the food of the stranger, and nourish

their bodies only on their own; and to seek a seat apart from

the natives, and have no contact with any of them as they lay at

meat. For if they partook of that food they would lose

recollection of all things, and must live for ever in filthy

intercourse amongst ghastly hordes of monsters. Likewise he told

them that they must keep their hands off the servants and the

cups of the people. |

|

Dan 8.14.9 (p. 240,31)

1 Duodecim

filii Guthmundi egregia indole totidemque filiae praeclui forma

circumsteterant mensas.

2 Qui

cum regem a suis dumtaxat illata delibare conspiceret, beneficii

repulsam obiciens iniuriosum hospiti querebatur.

3 Nec

Thorkillo competens facti excusatio defuit.

4 Quippe

insolito cibo utentes plerumque graviter affici solere

commemorat, regemque, non tam alieni obsequii ingratum quam

propriae sospitatis studiosum, consueto more corpus curantem

domesticis cenam obsoniis instruxisse.

5 Igitur

haudquaquam contemptui imputari debere, quod fugiendae pestis

salutari gereretur affectu. |

Round the table stood twelve noble sons of Gudmund, and as many

daughters of notable beauty. When Gudmund saw that the king

barely tasted what his servants brought, he reproached him with

repulsing his kindness, and complained that it was a slight on

the host. But Thorkill was not at a loss for a fitting excuse.

He reminded him that men who took unaccustomed food often

suffered from it seriously, and that the king was not ungrateful

for the service rendered by another, but was merely taking care

of his health, when he refreshed himself as he was wont, and

furnished his supper with his own viands. An act, therefore,

that was only done in the healthy desire to escape some bane,

ought in no wise to be put down to scorn. |

|

Dan 8.14.10 (p. 240,39)

1 Videns

autem Guthmundus apparatus sui fraudem hospitum frugalitate

delusam, cum abstinentiam hebetare non posset, pudicitiam

labefactare constituit, omnibus ingenii nervis ad debilitandam

eorum temperantiam inhians.

2 Regi

enim filiae matrimonium offerens, ceteris, quascumque e

famulitio peterent, potiendas esse promittit.

3 Plerisque

rem approbantibus, Thorkillus hunc quoque illecebrarum lapsum,

sicut et ceteros, salubri monitu praecurrit, industriam suam

inter cautum hospitem ac laetum convivam egregia moderatione

partitus.

4 Quattuor

e Danis oblatum amplexi, saluti libidinem praetulerunt.

5 Quod

contagium lymphatos inopesque mentis effectos pristina rerum

memoria spoliavit; quippe post id factum parum animo constitisse

traduntur.

6 Qui

si mores intra debitos temperantiae fines continuissent,

Herculeos aequassent titulos, giganteam animo fortitudinem

superassent perenniterque patriae mirificarum rerum insignes

exstitissent auctores. |

Now

when Gudmund saw that the temperance of his guest had baffled

his treacherous preparations, he determined to sap their

chastity, if he could not weaken their abstinence, and eagerly

strained every nerve of his wit to enfeeble their self-control.

For he offered the king his daughter in marriage, and promised

the rest that they should have whatever women of his household

they desired. Most of them inclined to his offer: but Thorkill

by his healthy admonitions prevented them, as he had done

before, from falling into temptation. With wonderful management

Thorkill divided his heed between the suspicious host and the

delighted guests. Four of the Danes, to whom lust was more than

their salvation, accepted the offer; the infection maddened

them, distraught their wits, and blotted out their recollection:

for they are said never to have been in their right mind after

this. If these men had kept themselves within the rightful

bounds of temperance, they would have equalled the glories of

Hercules, surpassed with their spirit the bravery of giants, and

been ennobled for ever by their wondrous services to their

country. |

|

Dan 8.14.11 (p. 241,11)

1 Adhuc

Guthmundus propositi pertinacia dolum intendere perseverans,

collaudatis horti sui deliciis, eo regem percipiendorum fructuum

gratia perducere laborabat, blandimentis visus illecebrisque

gulae cautelae constantiam elidere cupiens.

2 Adversum

quas insidias rex Thorkillo, ut prius auctore firmatus,

simulatae humanitatis obsequium sprevit, utendi excusationem a

maturandi itineris negotio mutuatus.

3 Cuius

prudentiae Guthmundus suam in omnibus cessisse considerans, spe

peragendae fraudis abiecta, cunctos in ulteriorem fluminis ripam

transvectos iter exsequi passus est. |

Gudmund, stubborn to his purpose, and still spreading his nets,

extolled the delights of his garden, and tried to lure the king

thither to gather fruits, desiring to break down his constant

wariness by the lust of the eye and the baits of the palate. The

king, as before, was strengthened against these treacheries by

Thorkill, and rejected this feint of kindly service; he excused

himself from accepting it on the plea that he must hasten on his

journey. Gudmund perceived that Thorkill was shrewder than he at

every point; so, despairing to accomplish his treachery, he

carried them all across the further side of the river, and let

them finish their journey. |

|

Dan 8.14.12 (p. 241,19)

1 Progressi

atrum incultumque oppidum, vaporanti maxime nubi simile, haud

procul abesse prospectant.

2 Pali

propugnaculis intersiti desecta virorum capita praeferebant.

3 Eximiae

ferocitatis canes tuentes aditum prae foribus excubare

conspecti.

4 Quibus

Thorkillus cornu abdomine illitum collambendum obiciens,

incitatissimam rabiem parvula mitigavit impensa.

5 Superne

portarum introitus patuit; quem scalis aequantes arduo potiuntur

ingressu.

6 Atrae

deintus informesque larvae conferserant urbem, quarum

perstrepentes imagines aspicere horridius an audire fuerit,

nescias; foeda omnia, putidumque caenum adeuntium nares

intolerabili halitu fatigabat.

7 Deinde

conclave saxeum, cui Geruthum fama erat pro regia assuevisse,

reperiunt.

8 Cuius

artam horrendamque crepidinem invisere statuentes, repressis

gradibus in ipso paventes aditu constiterunt. |

They went on; and saw, not far off, a gloomy, neglected town,

looking more like a cloud exhaling vapour. Stakes interspersed

among the battlements showed the severed heads of warriors and

dogs of great ferocity were seen watching before the doors to

guard the entrance. Thorkill threw them a horn smeared with fat

to lick, and so, at slight cost, appeased their most furious

rage. High up the gates lay open to enter, and they climbed to

their level with ladders, entering with difficulty. Inside the

town was crowded with murky and misshapen phantoms, and it was

hard to say whether their shrieking figures were more ghastly to

the eye or to the ear; everything was foul, and the reeking mire

afflicted the nostrils of the visitors with its unbearable

stench. Then they found the rocky dwelling which Geirrod was

rumoured to inhabit for his palace. They resolved to visit its

narrow and horrible ledge, but stayed their steps and halted in

panic at the very entrance. |

|

Dan 8.14.13 (p. 241,31)

1 Tunc

Thorkillus, haerentes animo circumspiciens, cunctationem

introitus virili adhortatione discussit, monens temperaturos

sibi, ne ullam ineundae aedis supellectilem, tametsi possessu

iucunda aut oculis grata videretur, attingerent, animosque tam

ab omni avaritia aversos quam a metu remotos haberent, neque vel

captu suavia concupiscerent vel spectatu horrida formidarent,

quamquam in summa utriusque rei forent copia versaturi.

2 Fore

enim, ut avidae capiendi manus subita nexus pertinacia a re

tacta divelli nequirent et quasi inextricabili cum illa vinculo

nodarentur.

3 Ceterum

composite quaternos ingredi iubet.

4 Quorum

Broderus et Buchi primi aditum tentant; hos cum rege Thorkillus

insequitur; ceteri deinde compositis gradiuntur ordinibus. |

Then Thorkill, seeing that they were of two minds, dispelled

their hesitation to enter by manful encouragement, counselling

them, to restrain themselves, and not to touch any piece of gear

in the house they were about to enter, albeit it seemed

delightful to have or pleasant to behold; to keep their hearts

as far from all covetousness as from fear; neither to desire

what was pleasant to take, nor dread what was awful to look

upon, though they should find themselves amidst abundance of

both these things. If they did, their greedy hands would

suddenly be bound fast, unable to tear themselves away from the

thing they touched, and knotted up with it as by inextricable

bonds. Moreover, they should enter in order, four by four.

Broder and Buchi (Buk?) were the first to show courage to

attempt to enter the vile palace; Thorkill with the king

followed them, and the rest advanced behind these in ordered

ranks. |

|

Dan 8.14.14 (p. 242,1)

1 Aedes,

deintus obsoleta per totum ac vi taeterrimi vaporis offusa,

cunctorum, quibus oculus aut mens offendi poterat, uberrima

cernebatur.

2 Postes

longaeva fuligine illiti, obductus illuvie paries, compactum e

spiculis tectum, instratum colubris pavimentum atque omni

sordium genere respersum inusitato advenas spectaculo

terruerunt.

3 Super

omnia perpetui foetoris asperitas tristes lacessebat olfactus.

4 Exsanguia

quoque monstrorum simulacra ferreas oneraverant sedes; denique

consessuum loca plumbeae crates secreverant; liminibus horrendae

ianitorum excubiae praeerant.

5 Quorum

alii consertis fustibus obstrepentes, alii mutua caprigeni

tergoris agitatione deformem edidere lusum.

6 Hic

secundo Thorkillus, avaras temere manus ad illicita tendi

prohibens, iterare monitum coepit. |

Inside, the house was seen to be ruinous throughout, and filled

with a violent and abominable reek. And it also teemed with

everything that could disgust the eye or the mind: the

door-posts were begrimed with the soot of ages, the wall was

plastered with filth, the roof was made up of spear-heads, the

flooring was covered with snakes and bespattered with all manner

of uncleanliness. Such an unwonted sight struck terror into the

strangers, and, over all, the acrid and incessant stench

assailed their afflicted nostrils. Also bloodless phantasmal

monsters huddled on the iron seats, and the places for sitting

were railed off by leaden trellises; and hideous doorkeepers

stood at watch on the thresholds. Some of these, armed with

clubs lashed together, yelled, while others played a gruesome

game, tossing a goat's hide from one to the other with mutual

motion of goatish backs. Here Thorkill again warned the men, and

forbade them to stretch forth their covetous hands rashly to the

forbidden things. |

|

Dan 8.14.15 (p. 242,12)

1 Procedentes

perfractam scopuli partem nec procul in editiore quodam suggestu

senem pertuso corpore discissae rupis plagae adversum residere

conspiciunt.

2 Praeterea

feminas tres corporeis oneratas strumis ac veluti dorsi

firmitate defectas iunctos occupasse discubitus.

3 Cupientes

cognoscere socios Thorkillus, qui probe rerum causas noverat,

docet Thor divum, gigantea quondam insolentia lacessitum, per

obluctantis Geruthi praecordia torridam egisse chalybem eademque

ulterius lapsa convulsi montis latera pertudisse; feminas vero

vi fulminum tactas infracti corporis damno eiusdem numinis

attentati poenas pependisse firmabat. |

Going on through the breach in the crag, they beheld an old man

with his body pierced through, sitting not far off, on a lofty

seat facing the side of the rock that had been rent away.

Moreover, three women, whose bodies were covered with tumours,

and who seemed to have lost the strength of their back-bones,

filled adjoining seats. Thorkill's companions were very curious;

and he, who well knew the reason of the matter, told them that

long ago the god Thor had been provoked by the insolence of the

giants to drive red-hot irons through the vitals of Geirrod, who

strove with him, and that the iron had slid further, torn up the

mountain, and battered through its side; while the women had

been stricken by the might of his thunderbolts, and had been

punished (so he declared) for their attempt on the same deity,

by having their bodies broken. |

|

Dan 8.14.16 (p. 242,21)

1 Inde

digressis dolia septem zonis aureis circumligata panduntur,

quibus pensiles ex argento circuli crebros inseruerant nexus.

2 Iuxta

quae inusitatae beluae dens, extremitates auro praeditus,

reperitur.

3 Huic

adiacebat ingens bubali cornu, exquisito gemmarum fulgore

operosius cultum nec caelaturae artificio vacuum; iuxta quod

eximii ponderis armilla patebat.

4 Cuius

immodica quidam cupiditate succensus, avaras auro manus

applicuit, ignarus excellentis metalli splendore extremam

occultari perniciem nitentique praedae fatalem subesse pestem.

5 Alter

quoque, parum cohibendae avaritiae potens, instabiles ad cornu

manus porrexit.

6 Tertius,

priorum fiduciam aemulatus nec satis digitis temperans, osse

humeros onerare sustinuit.

7 Quae

quidem praeda uti visu iucunda, ita usu prodigialis exstitit;

illices enim formas subiecta oculis species exhibebat.

8 Armilla

siquidem anguem induens venenato dentium acumine eum, a quo

gerebatur, appetiit; cornu in draconem extractum sui spiritum

latoris eripuit; os ensem fabricans aciem praecordiis gestantis

immersit.

9 Ceteri

sociae cladis fortunam veriti, insontes nocentium exemplo

perituros putabant, ne innocentiae quidem incolumitatem

tribuendam sperantes. |

As

the men were about to depart thence, there were disclosed to

them seven butts hooped round with belts of gold; and from these

hung circlets of silver entwined with them in manifold links.

Near these was found the tusk of a strange beast, tipped at both

ends with gold. Close by was a vast stag-horn, laboriously

decked with choice and flashing gems, and this also did not lack

chasing. Hard by was to be seen a very heavy bracelet. One man

was kindled with an inordinate desire for this bracelet, and

laid covetous hands upon the gold, not knowing that the glorious

metal covered deadly mischief, and that a fatal bane lay hid

under the shining spoil. A second also, unable to restrain his

covetousness, reached out his quivering hands to the horn. A

third, matching the confidence of the others, and having no

control over his fingers, ventured to shoulder the tusk. The

spoil seemed alike lovely to look upon and desirable to enjoy,

for all that met the eye was fair and tempting to behold. But

the bracelet suddenly took the form of a snake, and attacked him

who was carrying it with its poisoned tooth; the horn lengthened

out into a serpent, and took the life of the man who bore it;

the tusk wrought itself into a sword, and plunged into the

vitals of its bearer. The rest dreaded the fate of perishing

with their friends, and thought that the guiltless would be

destroyed like the guilty; they durst not hope that even

innocence would be safe. |

|

Dan 8.14.17 (p. 242,37)

1 Alterius

deinde tabernaculi postica angustiorem indicante secessum,

quoddam uberioris thesauri secretarium aperitur, in quo arma

humanorum corporum habitu grandiora panduntur.

2 Inter

quae regium paludamentum, cultiori coniunctum pilleo, ac

mirifici operis cingulum visebantur.

3 Quorum

Thorkillus admiratione captus, cupiditati frenos excussit,

propositam animo temperantiam exuens, totiesque alios informare

solitus ne proprios quidem appetitus cohibere sustinuit.

4 Amiculo

enim manum inserens, ceteris consentaneum rapinae ausum

temerario porrexit exemplo. |

Then the side-door of another room showed them a narrow alcove:

and a privy chamber with a yet richer treasure was revealed,

wherein arms were laid out too great for those of human stature.

Among these were seen a royal mantle, a handsome hat, and a belt

marvellously wrought. Thorkill, struck with amazement at these

things, gave rein to his covetousness, and cast off all his

purposed self-restraint. He who so oft had trained others could

not so much as conquer his own cravings. For he laid his hand

upon the mantle, and his rash example tempted the rest to join

in his enterprise of plunder. |

|

Dan 8.14.18 (p. 243,7)

1 Quo

facto, penetralia, ab imis concussa sedibus, inopinatae

fluctuationis modo trepidare coeperunt.

2 Subinde

a feminis conclamatum aequo diutius infandos tolerari praedones.

3 Igitur,

qui prius semineces expertiaque vitae simulacra putabantur,

perinde ac feminarum vocibus obsecuti, e suis repente sedibus

dissultantes vehementi incursu advenas appetebant.

4 Cetera

raucos extulere mugitus.

5 Tum

Broderus et Buchi, ad olim nota sibi studia recurrentes,

incursantes se Lamias adactis undique spiculis incessebant

arcuumque ac fundarum tormentis agmen obtrivere monstrorum.

6 Nec

alia vis repellendis efficacior fuit.

7 Viginti

solos ex omni comitatu regio sagittariae artis interventus

servavit, ceteri laniatui fuere monstris. |

Thereupon the recess shook from its lowest foundations, and

began suddenly to reel and totter. Straightway the women raised

a shriek that the wicked robbers were being endured too long.

Then they, who were before supposed to be half-dead or lifeless

phantoms, seemed to obey the cries of the women, and, leaping

suddenly up from their seats, attacked the strangers with

furious onset. The other creatures bellowed hoarsely. But Broder

and Buchi fell to their old and familiar arts, and attacked the

witches, who ran at them, with a shower of spears from every

side; and with the missiles from their bows and slings they

crushed the array of monsters. There could be no stronger or

more successful way to repulse them; but only twenty men out of

all the king's company were rescued by the intervention of this

archery; the rest were torn in pieces by the monsters. |

|

Dan 8.14.19 (p. 243,17)

1 Regressos

ad amnem superstites Guthmundus navigio traicit exceptosque

domi, cum diu ac multum exoratos retentare non posset, ad

ultimum donatos abire permisit.

2 Hic

Buchi parum diligens sui custos, laxatis continentiae nervis,

virtute, qua hactenus fruebatur, abiecta, unam e filiabus eius

irrevocabili amore complexus, exitii sui connubium impetravit,

moxque repentino verticis circuitu actus, pristinum memoriae

habitum perdidit.

3 Ita

egregius ille tot monstrorum domitor, tot periculorum subactor,

unius virginis facibus superatus, peregrinatum a continentia

animum miserabili iugo voluptatis inseruit.

4 Qui

cum abiturum regem honestatis causa prosequeretur, vadum

curriculo transiturus, altius desidentibus rotis, vi verticum

implicatus absumitur. |

The

survivors returned to the river, and were ferried over by

Gudmund, who entertained them at his house. Long and often as he

besought them, he could not keep them back; so at last he gave

them presents and let them go. Buchi relaxed his watch upon

himself; his self-control became unstrung, and he forsook the

virtue in which he hitherto rejoiced. For he conceived an

incurable love for one of the daughters of Gudmund, and embraced

her; but he obtained a bride to his undoing, for soon his brain

suddenly began to whirl, and he lost his recollection. Thus the

hero who had subdued all the monsters and overcome all the

perils was mastered by passion for one girl; his soul strayed

far from temperance, and he lay under a wretched sensual yoke.

For the sake of respect, he started to accompany the departing

king; but as he was about to ford the river in his carriage, his

wheels sank deep, he was caught up in the violent eddies and

destroyed. |

|

Dan 8.14.20 (p. 243,27)

1 Rex

amici casum gemitu prosecutus, maturata navigatione discessit.

2 Qua

primum prospera usus, deinde adversa quassatus, periclitatis

inedia sociis paucisque adhuc superstitibus, religionem animo

intulit atque ad vota superis nuncupanda confugit, extremae

necessitatis praesidium in deorum ope consistere iudicans.

3 Denique,

aliis varias deorum potentias exorantibus ac diversae numinum

maiestati rem divinam fieri oportere censentibus, ipse

Utgarthilocum votis pariter ac propitiamentis aggressus,

prosperam exoptati sideris temperiem assecutus est. |

The

king bewailed his friend's disaster and departed hastening on

his voyage. This was at first prosperous, but afterwards he was

tossed by bad weather; his men perished of hunger, and but few

survived, so that he began to feel awe in his heart, and fell to

making vows to heaven, thinking the gods alone could help him in

his extreme need. At last the others besought sundry powers

among the gods, and thought they ought to sacrifice to the

majesty of divers deities; but the king, offering both vows and

peace-offerings to Utgarda-Loki, obtained that fair season of

weather for which he prayed. |

|

Dan 8.15.1 (p. 243,35)

1 Domum

veniens, cum tot maria se totque labores emensum animadverteret,

fessum aerumnis spiritum a negotiis procul habendum ratus,

petito ex Suetia matrimonio, superioris studii habitum otii

meditatione mutavit.

2 Vita

quoque per summum securitatis usum exacta, ad ultimum paene

aetatis suae finem provectus, cum probabilibus quorundam

argumentis animas immortales esse compertum haberet, quasnam

sedes esset, exuto membris spiritu, petiturus, aut quid praemii

propensa numinum veneratio mereretur, cogitatione secum varia

disquirebat. |

Coming home, and feeling that he had passed through all these

seas and toils, he thought it was time for his spirit, wearied

with calamities, to withdraw from his labours. So he took a

queen from Sweden, and exchanged his old pursuits for meditative

leisure. His life was prolonged in the utmost peace and

quietness; but when he had almost come to the end of his days,

certain men persuaded him by likely arguments that souls were

immortal; so that he was constantly turning over in his mind the

questions, to what abode he was to fare when the breath left his

limbs, or what reward was earned by zealous adoration of the

gods. |

Saxo's description of that house of torture, which is found within the city, is not unlike Völuspá's description of that dwelling of torture on the Náströnds ["corpse-shores"]. In Saxo, the floor of the house consists of serpents wattled together, and the roof of sharp stings. In Völuspá, the hall is made of serpents braided together, whose heads from above spit venom down on those dwelling there. Saxo speaks of soot a century old on the door frames; Völuspá of ljórar, air- and smoke-openings in the roof.

Saxo himself points out

that the Geruthus (Geirröðr)

mentioned by him, and his famous daughters, belong to the myth about

the god Thor. That Geirrod after his death is transferred to the

lower world is no contradiction to the heathen belief, according to

which beautiful or terrible habitations await the dead, not only of

men but also of other beings. Compare

Gylfaginning 42, where Thor with one blow of his Mjölnir sends a

giant niðr undir Niflhel.

When the Danish adventurers had left the horrible city of fog in

Saxo's saga about Gorm, they came to another place in the lower

world where the gold-plated mead-cisterns were found. The Latin word

used by Saxo, which I translate with cisterns of mead, is

dolium. In the classical

Latin, this word is used in regard to wine-cisterns of so immense a

size that they were counted among the immovables, and usually were

sunk in the cellar floors. They were so large that a person could

live in such a cistern, and this is also reported as having

happened. The size is therefore no obstacle to Saxo's using this

word for a wine-cistern to mean the mead-wells in the lower world of

Germanic mythology. The question now is whether he actually did so,

or whether the subterranean dolia in question are objects in regard to which our earliest mythic

records have left us in ignorance.

In Saxo's time, and earlier, the epithets by which the mead-wells -

Urd's and Mimir's - and their contents are mentioned in mythological

songs had come to be applied also to those mead-vessels which Odin

is said to have emptied in the halls of the giant Fjalar or Suttung.

This application also lay near at hand, since these wells and these

vessels contained the same liquor, and since it originally, as

appears from the meaning of the words, was the liquor, and not the

place where the liquor was kept, to which the epithets

Óðrærir, Boðn, and

Són applied. In

Hávamál 107, Odin expresses his joy that

Óðrærir has passed out of the possession of the giant Fjalar and can

be of use to the beings of the upper world. But if we may trust

Skáldskaparmál 6, it is

the drink and not the empty vessels that Odin takes with him to

Valhall. On this supposition, it is the drink and not one of the

vessels which in Hávamál is called Óðrærir.

In Hávamál 140, Odin

relates how he, through self-sacrifice and suffering, succeeded in

getting runic songs up from the deep, and also a drink dipped out of

Óðrærir. He who gives him

the songs and the drink, and accordingly is the ruler of the

fountain of the drink, is a man, "Bölthorn's celebrated son." Here

again Óðrærir is one of

the subterranean fountains, and no doubt Mimir's, since the one who

pours out the drink is a man. But in the second stanza of

Forspjallsljóð, Urd's

fountain is also called

Óðrærir (Óðhrærir

Urðar). Paraphrases for

the liquor of poetry, such as "Boðn's growing billow" (Einar Skálaglamm) and "Són's

reed-grown grass edge" (Eilífr Guðrúnarson,

Skáldskaparmál 10, Jónsson

edition), point to fountains or wells, not to vessels. Meanwhile, a

satire was composed before the time of Saxo and Sturluson about

Odin's adventure at Fjalar's, and the author of this song, the

contents of which the Prose

Edda has preserved, calls the vessels which Odin empties at the

giant's Óðhrærir, Boðn,

and Són (Skáldskaparmál

5-6, Jónsson ed.). Saxo, who reveals a familiarity with the genuine

heathen, or supposed heathen, poems handed down to his time, may

thus have seen the epithets

Óðrærir, Boðn, and Són

applied both to the subterranean mead-wells and to a giant's

mead-vessels. The greater reason he would have for selecting the

Latin dolium to express an

idea that can be accommodated to both these objects.

|

Veit

hún Heimdallar undir heiðvönum helgum baðmi. |

hearing is hidden beneath the bright-accustomed holy tree. |

Near one of the mead-cisterns in the lower world, Gorm's men see a horn

ornamented with pictures and flashing with precious stones.

Two of the sagas, Helgi Thorisson's

and Gorm's, cast a shadow on Gudmund's character. In the former,

this shadow does not produce confusion or contradiction. The saga is a

legend which represents Christianity, with Olaf Tryggvason as its

apostle, in conflict with heathenism, represented by Gudmund. It is

therefore natural that the latter cannot be presented in the most

favorable light. With his prayers, Olaf destroys the happiness of

Gudmund's daughter. He compels her to abandon her lover, and Gudmund,

who is unable to take revenge in any other manner, tries to do so, as is

the case with so many of the characters in saga and history, by

treachery. This is demanded by the fundamental idea and tendency of the

legend. What the author of the legend has heard about Gudmund's

character from older sagamen, or what he has read in records, he does

not, however, conceal with silence, but admits that Gudmund, aside from

his heathen religion and grudge toward Olaf Tryggvason, was a man in

whose home one might fare well and be happy.

Hervör's saga says that Gudmund was wise, mighty, in a heathen sense

pious ("a great sacrificer"), and so honored that sacrifices were

offered to him, and he was worshipped as a god after death. Bosi's saga

says that he was greatly skilled in magic arts, which is another

expression for heathen wisdom, for

fimbul-songs, runes, and incantations.