An Investigation of Saxo's Telling of

the Bride-Winning of Gerd

by Carla O'Harris & Siegfried Goodfellow

© 2014

|

|

|

|

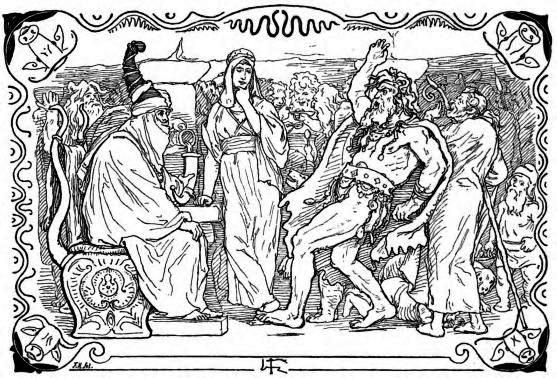

If

Skírnismál has burlesque elements, Saxo's

account of the retrieval of Gerd in Book Five of his

Gesta Danorum is pure situation

comedy and slapstick. It is not only funny, but zany. Moreover,

it shows signs that it was originally a stage play. Scholars

believe Skirnismal

was acted, because of speaking parts in the manuscript indicated

next to various strophes, but Saxo's account also shows every

sign of being acted out on a stage. Saxo tells us in Book Six

that there was a stage at Uppsala where the Sons of Frey would

enact "effeminate gestures" or dances, and the "mimes" would

clap with bells and so forth at the time of the sacrifices.

Besides conjuring up imagery of Morris Men, there is every

reason to think that the Myth of Frey would be enacted in

various forms, and that which led to his wedding, his being a

God of Nuptials and Fertility, would be foremost.

|

||||||

Saxo says,

|

||||||

|

The whole passage is important, because it sets the tone

of what was being shown on stage. It may be, as in Shakespeare's

day, that women's parts might have been played by men, and it is

traditional in such cases for women's parts to be

overexaggerated by the male actors in "swishy" kinds of ways.

Traditional festival mumming closely associated with Frey

included a stock drag-queen character as well, so this would not

be beyond the stage-activities that might have been found here.

Starkad definitely found the shows to be lascivious, which means

they must have been quite ribald -- appropriate not only for

comedy, but for a fertility god. "Mimes" doesn't just mean pantomimers -- it also has a connotation in Latin of an actor specifically performing in a comedy. There must have been dancing and quite a lot of pageantry indicated by the bells and rattles -- which could even suggest a shamanic component. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

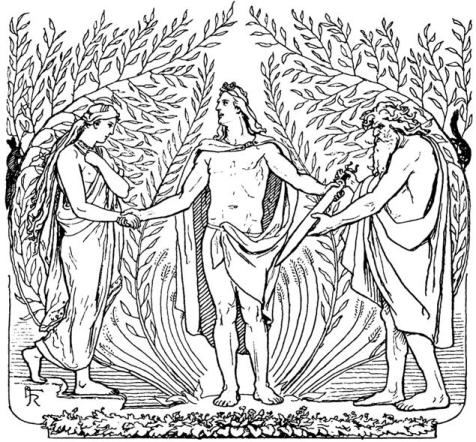

Sif, on the other hand, is completely veiled, and claims to be the sister of Freya. One can immediately see the similarities with Þrymskviða. This is yet another "fooling of brides" at a Giant's home that will be broken apart in the end by violence -- again, on Thor's part. Just as Thor was once veiled up, so will his wife Sif be. And just as the Gods clearly had fun in Þrymskviða, which just springs with jolliness from its telling, so they do here. One of the joys of outwitting the giants is that despite the fact that they can at times be clever, ultimately, they're not too terribly bright, and the Gods get great humor out of tricking them. The fact that there is so much comedy in the Gods' approach to the giants is also an indication to the audience the degree of their power -- they have that level of confidence. On another level, however, the gambit is quite risky. Odr, Freya, and Sif are going deep into the underworld -- to an area near the Bottom of the Ocean where Aegir's Hall is, and where Ran collects drowned soldiers she or her evil sea-spirits have been able to collect. They are headed, in other words, into the Enemy's Lair. It has not been so long since Freya has been in the hands of giants, and here she is going right back in -- albeit to a different giant's lair. Sure, this time, Thor's men are standing by nearby at a safe location, but it's still a risk. Yet Saxo's telling treats it like a jolly Þrymskviða-style lay, another indication this was a festival skit or stage comedy at the Uppsala holiday sacrifices. We have reason to believe that Odr took no chances, however, and that Njord was also standing by very closely, even though this is not explicitly indicated. We will look at this shortly. Odr agrees to Gymir's wife-swapping offer, but insists that the wedding festivities take place simultaneously. All they need do is have a partition in the hall, and each party can celebrate on either side. While Gymir celebrates his nuptial-feast with Freya, Odr will celebrate with Alfhild-Gerd.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

The shtick, of course, is, that Gymir leaves Freya's

side to go over and see how his daughter is enjoying the feast

with Odr. Freya has slipped through the partition and sits next

to Odr. Gymir asks why Freya is sitting there, and how she got

there, when she was just on the other side. The farcical nature

of this comes out immediately. Audiences were already laughing.

Freya claims she is Sif -- her sister. Gymir exclaims that she

looks exactly like Freya, and she responds, why yes, people have

always thought so. Gymir is suspicious, however, so he runs

around the partition again, and as he does so, Freya slips

through again to her original seating, there smiling innocently. |

||||||

1. A situation comedy. |

||||||

|

Shakespeare would have had a field day with this plot. It is surprising that to this day, this extraordinarily humorous and adventuresome plot not only remains unstaged or treated in any way in the drama, but remains virtually without comment by scholars.

It should be noted that, in accordance with Skírnismál

highlighting Gerd's aelfscine, she is called here "Alfhild".

"Elf" is right in her name. Moreover, she receives the "-hild"

suffix that I have consistently traced to those in Sol or

Sunna's lineage, indicating she was a dis of light. Whatever her

giant heritage, she definitely has other heritage running in her

veins as well.

In Skírnismál, there are two implied social forces thwarting Frey’s desires. The first, is as we said, Odin, who while not Frey’s immediate father, functions as “All Father”. The second is the feuding social structure of the Gods and the Giants, which here functions as the original Montagues and Capulets, across whose feuding boundaries, love is forbidden. In Saxo’s play, the forbidding figure is a father, too, but this time, it is Gerd-Alfhild’s father, Gymir-Gotar (Aegir) who will not permit the bride and betrothed to marry, but tries to control who she shall marry, according to his will and his desire for social alliances. He literally is a double-thwarter, as he tries to separate two couples, Frey and Gerd, and Freya and Odr. But of course, if he intends to double-thwart, he will, in turn, be comically double-thwarted, as his intended marriages are turned into mock-weddings, mock-weddings that in all their hilarity will only facilitate and accelerate the intended wedding of Frey and Gerd. Some comments by Helen Gardner in her assessment of “As You Like It” (Herbert Weil, Jr., op cit) are relevant here. She underlines aspects of comedy I have themed as Spring motifs. “The great symbol of pure comedy is marriage by which the world is renewed, and its endings are always instinct with a sense of fresh beginnings. Its rhythm is the rhythm of the life of mankind, which goes on and renews itself as the life of nature does.” In this light, it is obvious why youth must triumph in comedy, for the life of the species must go on, and thwarters cannot be allowed to ultimately block this. But it is her comments that follow that particularly shed light on some of the antics in Saxo’s piece. “Comic plots are made up of changes, chances and surprises. Coincidences…heighten comic feeling. It is absurd to complain in poetic comedy of improbable encounters and characters arriving pat on their cue…” When we think of all the improbable complications in Saxo’s plot – Freya shifting back and forth from one side of the room (or stage, as I’ve argued) to another, and Freya and Odr getting to sleep together after the banquet despite its riskiness, or the just-in-the-nick-of-time arrival of the cavalry when Thor bursts in, and so forth, her comments make a tremendous amount of sense. And she contrasts the comedic affirmation of the life of the species to the tragic mourning of “the rhythm of the individual life which comes to a close, and its great symbol is death.” This helps us place our comedy. The weddings of Freya and Odr, Skadi and Njord, Sif and Thor, Hanunda and Ullr, and Idunn and Bragi, are grand finales of Spring in a literal mythic battle against Winter which is the epic arc of the “Frost War”. Idunn and Freya return, and Spring takes its course. It is a triumph of triumphs – but shortly thereafter, there is a tragic interlude that arrays dark clouds around this comedy and makes it more somber. When Skadi arrives in Asgard and ends up betrothing Njord, Baldur is still amongst the Gods, as her initial desire is for him. But by the time Skirnir makes his descent to woo Gerd for Frey in Skírnismál, Draupnir has already been burnt on Baldur’s pyre and been brought back to the Gods by Hermodr (Svipdag-Odr-Skirnir). Thus, the tragic “close” “of the individual life”, with “its great symbol [of] death”, has played out in the Death of Baldr, in the most sobering and terrible of ways. It is time for a comedy again. Wise dramatists intersperse tragedies and comedies, and our ancestors were no different. Frey is the perfect protagonist, because he was left out of the previous wedding-cycle, and has been further saddened by the death of his kinsman Baldr, and needs something – as we all, the audience, do – to lighten the mood and give a sense that life as a whole can recover after its tragic dénouement on the individual level. We can argue here that Skírnismál and Saxo’s telling constitute a double-punch of comic infusion, doubly necessary to offset the elegiac mood of Baldr’s tragedy. If we consider Frey’s Bride-Winning as a two-act play, perhaps each act enacted on different days if not the same day, Skírnismál would constitute Act I, while Saxo's telling would constitute Act II. Together, they both have adventure, comedy, and burlesque, and perhaps there would have been an interlude between the two acts celebrating the betrothal at Barri, perhaps even with handfasting rituals of assembled couples, or some sort of Morris Men dance that had suggestive movements -- the kind that offended Starkad. With the details we have, a very lovely and quite funny romantic comedy could be constructed, one that could bear close resemblances to a performance that Saxo may very well have either witnessed, in skit form, or heard of from some elder who had seen it with his own eyes. And the alternation of tragedy and comedy we have explored above – which we traditionally associate with the masks of Melpomene and Thalia, the stock faces of the comic grin and the tragic grimace which have become the traditional symbol of the theatre – fits well with the structure of sacrifice which Saxo frames around the comic mimings on the stage of Uppsala. Adam of Bremen has emphasized the “tragic” aspects of these sacrifices, where every nine years, there were great slaughters of animals, followed, of course, by feasts. In this first tragic act, an animal is killed, and here we may see how the animal could stand in for the death, say, of Baldur. This may even have been accompanied by skits or rituals mourning the death. But once this mourning aspect of the slaughter is accomplished, the feast follows, and comedy is appropriate to the feast. Here is where Saxo’s emphasis on the cavorting mimes and dancers comes in. Here is where the marvelous Two-Act play of Frey’s Bride-Winning seasons the feast and sparkles the mead with that joyous, and even rollicking, element of festive mirth. |

||||||

|