|

Who Is Gotar? An Investigation by Carla O’Harris & Siegfried Goodfellow |

|

|

Saxo presents us with a comic episode of the retrieval of a bride for Frodi-Frey, as we have seen, and makes the bride’s father one Gøtar. By his very position as the father of Frey’s bride, we would equate him with Gymir, the giant-father of Gerd, who is presented as the formidable giant of the sea, Aegir. In Skirnismal, the only hope Skirnir has against this “all mighty” giant is the magic sword Frey gives him. Is there evidence elsewhere that would make a giant-figure out of Gøtar, one who lived by the sea, as Aegir-Gymir does? |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Indeed. In a translated excerpt from the Fljotsdaela Saga, W. G. Collingwood, “A Legend of Shetland from Fljotsdaela Saga”, in Saga-Book of the Viking Club, Volume V, Part II, Viking Club, London, April 1908, pp. 278 – 286, we find: “A giant called Geitir … He is the cause of great mischief; he maims both man and beast, and he is the evillest wight in all Shetland.” His depredations are the reason why even at the great festival of Yule, all are sullen and glum, hardly touching their food. The image is strikingly similar to the dismal atmosphere that the marauding Grendel casts upon the meadhall, taking away from what should be a holiday atmosphere of joy, and for similar reasons: Geitir, as Grendel, maims “man and beast”, and kidnaps maidens. “[H]e goes out of nights to plunder”. He is described as “the greatest enemy in the country.” And as it turns out, Geitir’s lair, like Grendel’s, lies in a watery region, in caves near or beneath the water. “Geitir’s cave or Geitir’s crag” is a cove contiguous with the sea, in which the water gets deeper when the tide is high. “…I went out toward the sea over great sands at ebbtide. When I had crossed the sands there was a green cove in front of me, and when I went through the cleft of the rocks great tangles of seaweed had grown there. Then shorewards and upbank I saw a great height or fell. In the fell yonder were crags looking toward the sea, and a great high rock. And I thought there were shallows beyond, and deep sea. Then I came to gravelbeds, and walked along them between the sea and the rock. Then in front of me was a great cave, and I went into it. I saw there a light burning, of such a kind that it threw no shadows. I saw an iron pillar in the cave, standing up to the roof, and to that pillar was tied a girl.” “Geitir’s Pillars” are the name of the mountain in which the crag or cove is situated by the shore. His “lair” or “cave” is filled with “gold and treasures”, a “heap of goods” and “all sorts of good things which were better to have than to lack.” |

|||||

|

|||||

|

The place is described very specifically again: “He went to the place where the green cove spread out, and the cleft in the rocks, and the great tangle of seaweed: there before him lay the gravel-beds. He went on to the place where the shallows were, and waded through them. At last he came to the spot he had seen in his dream, and climbed up to the cave, and entered it. He saw the light burning; on the further side he saw a bed-place, much bigger than he had ever seen such a thing before…” There is no doubt that this describes a series of sea-caves and cliffs by the ocean. We should note that Gymir’s wife Aurboda is described by Snorri as a bergrisa, a “cliff-giant”, while Aegir is described in Hymiskvida as a bergbúi, a “cliff-dweller”. describing cliffs off the shore of Gymir’s place, whose house is called “mighty and fair” by Snorri. The description inFljotsdaela Saga is rich and picturesque, just the kind of environment we would expect a sea-giant to live in, in rocky crags by the ocean, in which the tide rushes in, situated in sea coves filled with seaweed and treasure. We ought to compare the “burning” “light” in Geitir’s lair with the lýsigull … fyrir eltzliós, “illuminated gold instead of fire-light” that Lokasenna describes as characteristic of Aegir’s place (and Lokasenna specifically tells us that Ægir, er öðro nafni hét Gymer, “Aegir, who is called by another name, Gymer”). Similarly, Gymir’s court is surrounded byvafrloga, “wavering flames”, whose flickering must obviously be a source of light. On the other hand, in Geitir’s lair, where there is the bright light that threw no shadows, there was a maiden. Similarly, Gymir’s daughter Gerd is specifically said to throw forth a magnificent light from her body so bright it lights both the heavens and the seas. It turns out that Geitir keeps a magnificent and very old sword, by the description, made of bronze, above his gigantic beds. “Over it he saw a great sword hanging. He took it down, and then followed a mighty fall of stones. The sword was well fitted with its sheath; its pommel and guard were of iron, most beautifully ornamented. He drew the sword, and it was green in colour, but brown at the edges; there were no flecks of rust on the sword. He had never seen a weapon like it.” The sword is so powerful that it easily hews through iron fetters, and indeed, may be used to kill Geitir himself, even though he is described as enormously huge even for a giant (his “head reached heavenward, much higher than the rock”, the rock here being the giant crag). In fact, Geitir himself says that the sword is “the only weapon that could hurt me”. Geitir lays a curse upon the sword, that although it will be passed down through the owner’s family, it will never prove of help when they are really in need. To this sword we must compare the gambanteinn that Skirnir carries to protect him from Gymir, a sword which fights giants on its own, and which, according to Lokasenna, ends up with Gymir, as Frey “sold it” in exchange for Gymir’s daughter. Thus, the fact that we find Geitir with a tremendously powerful sword should be taken as no coincidence. (We might also note that in the lair of Grendel’s mother, we find a powerful sword in those sea-caverns as well.) |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Saxo describes a Gøtar who is the father of the bride

destined for Frodi-Frey, and whose features are entirely

congruous with what the Fljotsdaela Saga tells us of

Geitar. Saxo’s description of Gøtar’s dwelling (he actually

calls it his penates, or ancestral home) in Book Five of Gesta

Danorum places it close to the sea, just as Geitar’s lair is by

the waters. This regiae, “palace” or “court”, is so close to the

shoreline that Gøtar, upon merely hearing the horn of the enemy,

may praeceps fugam navigio, “quickly

flee in a ship”. Like in the Shetland legend, he is also

described as someone who kidnaps maidens, who through raptuiand latricinio, “rape

and robbery”, seeks out love. And his place, like Geitar’s, is

so filled with treasure, that it took the plunderers “half the

night” to get out all this praedis, “booty”,

andsupellectilem, “household

furnishings and ornaments”. There is no doubt that Saxo’s Gøtar and Fljotsdaela Saga’s Geitir are one and the same giant. The composite picture is of a sea-giant who lives in treasure-coves by the shoreline, illuminated by magical light, in which he traps maidens he has seized, and who, according to Saxo, has an elfin daughter (Alfhild – and here let us remember the aelfscine which, not in so many words, Skirnismal describes Gerd) desired by Frodi-Frey, and who ends up with Frodi-Frey, through the explicit help and wooing of Frodi-Frey’s chief servant. All of this is completely congruent with, and dovetails into, Gymir-Aegir’s characteristics as the father of Gerd. Polynymy is a general characteristic of mythic figures, particularly in Norse mythology, and we already know that Aegir has at least two other names, Gymir and Hler. Aegir, whose very name means “ocean”, and whose wife, Ran, is said to drag sailors down to the bottom of the sea, must have his palace situated near the ocean bottom. He ends up with a tremendous kettle for brewing there in his place, as he becomes the God’s brewer. The underworld nature of this situation suggests it could even be in the vicinity of Hvergelmir, the “roaring kettle”. Hymiskvida says that there was an ørkost of kettles or cauldrons in Aegir’s place, originally, which literally is “lack of choice”, but may mean in context “unsuitable” for the purpose of brewing for all the Gods. While it could indicate that prior to Tyr and Thor’s mission there were no cauldrons at all in Aegir’s place, the greater likelihood is that of the cauldrons already there, none were suitable enough to satisfy all the Gods. The many different smaller kettles thus suggested in Hymiskvida could even suggest boiling pools such as can be found in caverns. |

|||||

|

|||||

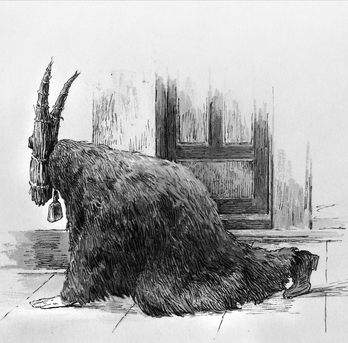

What can we glean from the name? It definitely means

“goat” or “goats”. We might note here that Gymir is specifically

said to have a shepherd in Skirnismal, and Chronicon

Lethrense lets us know that Aegir-Hler had King Snae as a

shepherd. The character has herds who need to be taken care of,

that may very well have included goats. Skirnismal describes all

kinds of underworld tortures, which include being given “goat

piss” to drink, and Gymir’s place is definitely situated near

these afterlife torture-zones, because Gymir’s shepherd declares

that if Skirnir is coming to Gymir’s court, he must be already

dead or fated to die, suggesting that souls are sent for

punishment to Gymir’s place. Rydberg has noticed that in Saxo’s

description in Book Eight of Gesta Danorum of Thorkill’s visit

to the smoking city of the damned in the underworld, certain

guardians are described as cavorting in goat-skins before the

threshold of places of torture. If we go to Saxo’s Latin, we

find, liminibus horrendae ianitorum excubiae praeerant. Quorum

alii consertis fustibus obstrepentes, alii mutua caprigeni

tergoris agitatione deformem edidere lusum. “At the threshold,

horrible doorkeepers were in charge of keeping watch. While

some, with clubs fastened together, roared, others sported

together, shaking a deformed goat hide spread over them.” This

last sentence may also be rendered, “While others, in a deformed

goat hide spread over them, shook in a kind of game.”

In any case, the image is of a kind of mumming, where they appear in some kind of goat-costume, even of the ulfhednar or shape-shifting type, albeit definitively caprigeni, born of goats. Even the activity with the clubs consertis, “brought together” or even “contending against each other” (initially, Latin concertare denoted a kind of contest or dispute, and through that, a kind of game), suggests that kind of Morris man dance conducted with clubs or sticks. It is also reminiscent of the “Wild Men” or woodwoses of European lore and carnival, who appeared in iconography with clubs, and who often danced and cavorted in hairy skins at pageants.

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Indeed, the description of Geitir’s lair in Fljotsdaela Saga paints a vivid backdrop to Saxo’s tale, and would prove useful in any set design that arranged to dramatize the play. We can imagine dripping cavern sounds, as well as the swill of the tides, which it is interesting to note are called in a strophe of Ynglingital, Gymis Ljod, “Gymir’s Song”. We would visualize seaweed hanging from various rock-like paper-machie formations, as well as the possibility of fish strewn about. Incidentally, this setting helps solve a problem of translation in Hymiskvida,where at the beginning of the poem, the Gods were said to have been veiðar námu, “hunting”, in the Ár or “yore-days” at the beginning of time. But given that veiðar can also mean “to fish”, and is often associated with fishing, the setting suggests it should be translated “taking fish”, ie., fishing. That would place them right by the sea-shore, near to where we would expect to find Aegir’s place. In fact, we do find the Gods by the sea-shore in the beginning of time.Gylfaginning 9 says that Bor’s sons were gengu með sævarströndu, “walking amidst the sea strands”, when they came upon Ask and Embla and transformed them into people, by giving of their very substance. It is possible that exhausted from this afterwards, they needed to replenish themselves, and fished in the waters nearby. Wanting to celebrate their accomplishment, the Gods sumblsamr, “wished together for sumble”, at which they could toast each other, but lacked for drink, and upon examining the lot-sticks, found that there were some drinking cauldrons at Aegir’s, whereupon he was ordered to brew for them. It is, of course, not necessary that the two narratives directly follow each other, as there are several instances connecting the Gods to the shores. Heimdall, as Rig, is said to walk along the shore, and of course, he himself was born from nine giants who would seem to be the nine daughters of Aegir, the “nine waves”. If Aegir gave his daughters as brides to the Gods, this would suggest an alliance perhaps cemented at the periodic winter sumbles. Indeed, as we do not know the origin of Thor’s two goats who pull his chariot, is it possible if Geitir-Aegir was known for his herd of goats, that they might have been gifts confirming that alliance? If the alliance had been broken, as it surely was during the Frost War, when there was a great naval battle at Froka-strand between Fridlief-Njord and Volund, and the great ur-tsunami overtook and flooded the land, indicating a direct rebellion of Aegir against Njord, then afterwards, as part of the peace-process, it would have to be glued back together and reconfirmed by a series of gifts. As we know from Northern lore, there is no more solid way to do this than through bride-giving, which explains, in terms of the alliances, why Frey ends up with one of Aegir’s daughters as a bride. | |||||

|

|||||

| Footnote | |||||

|

A caveat is in order here in terms of interpreting the figure of Gøtar in Book Five of Saxo’s Gesta Danorum. We have seen in other investigations, as first observed by Rydberg, that Saxo often confuses mythic figures with very similar names, exemplified most particularly in Book Three where he conflates Otherus and Hotherus, subsuming both under the latter, whereupon the lore-student must meticulously separate the strands. Similarly, it would appear that there are two figures that Saxo has Latinized as Gøtarus here. We have sufficiently demonstrated that the figure who is the father of Frodi-Frey’s bride is Geitir, the giant. But Saxo speaks of Ericus-Odr as being at the court of Gøtar and receiving from him the ship Skrøter along with his appellation Disertus, “The Eloquent.” The Gøtar with whom Ericus contends in the Pseudo-Weddings acts as if this title is new to him, and Eric speaks of it as well as something that Gøtar knows little of. But the king with whom the young son of Groa would have been fostered was King Halfdan-Gram, a human king under the patronage of Thor. Gotar can mean “of the Goths”, who originally inhabited Sweden. Halfdan, as a famous king who eventually reconquered Sweden from the hands of Volund, could very well be given a title, amongst others, of king “of the Goths”, and thus, Gøtar would not be inappropriate for him. If Saxo came across this appellation of him, he could easily have confused it with the Geitir he Latinizes as Gøtarus. Thus, we must distinguish the first Gøtar, who is Halfdan, and in whose court we find the young Ericus before his rescue of Freya-Gunvara, from the second Gøtar, who is the giant Geitir-Aegir-Gymir. |