How Passages in the Eddas Act as

References to Constellations

by Dr. Christopher E. Johnsen

© 2014

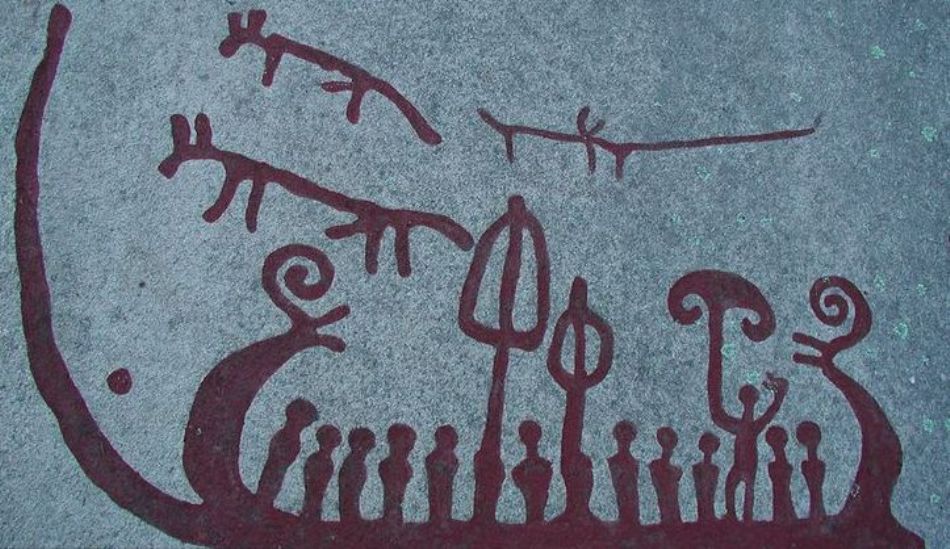

Image from Bronze Age Petrogylphs Böhuslan, Sweden |

The Norse Myths have a distinctive flavor all their own, but they also

have many similarities to the Greek, Roman, Persian and Indian mythologies.

These myths from other cultures have many well-known

correspondences with the stars, whereas the Norse mythical tradition has a

paucity of them, or perhaps it would be better to say that they have been

intentionally hidden and the keys to deciphering these correspondences have been

lost.

Modern astronomy’s roots can be traced to

Mesopotamia, and it descends directly from Babylonian astronomers who in turn

derived their knowledge from Sumerian astronomers. The earliest Babylonian

star catalogues date from about 1200 BC and many star names are in Sumerian

suggesting that the Sumerians were one of if not the first people to study the

stars that have been observed in the archeological record or that they inherited

an astronomical tradition from some unknown earlier culture.

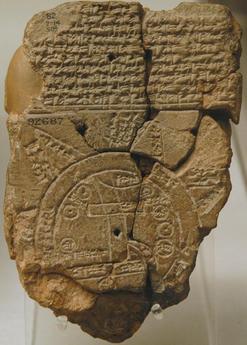

The Sumerians developed the earliest known writing system - cuneiform – whose

origin is currently dated to circa 3500 BC. Baked clay tablets with

cuneiform writing have been found that recorded detailed observations of the

stars which led to the sophisticated astronomy of the Sumerian’s successors, the

Babylonians. Only fragments of these cuneiform tablets detailing Babylonian

astronomy have survived down through the ages. Many believe that "all subsequent

varieties of scientific astronomy, in the Hellenistic world, in India, in Islam,

and in the West—if not indeed all subsequent endeavour in the exact

sciences—depend upon Babylonian astronomy in decisive and fundamental ways."(1)

An argument can be made that this statement also holds true for the Norse

astronomers of old and that they were continuing the ancient Sumerian/Babylonian

tradition.

|

The Sumerians created the concept of planetary gods and also used a sexagesimal (base 60) number system. This method of calculation facilitated the manipulation of both very large and very small numbers and is the basis for the modern practice of divvying up a circle into 360 degrees. The number 60 has twelve factors, namely 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30 and 60. With so many factors, manipulation of fractions involving sexagesimal numbers are simplified. |

Astronomy can be used for determining both time and location by careful

observation, thus making it useful for agricultural purposes to be able to

observe and record the cyclical movements of the moon, stars and planets as well

as for navigation on land and by sea.

Since the Norse were an agricultural society, the

welfare of the people depended upon timing planting properly and study of the

stars could be used to create a calendar in order to maximize the turnout of the

crops. They were also mariners and travelled vast distances between different

lands on the sea and needed an accurate method of navigation in order to get to

where they were going.

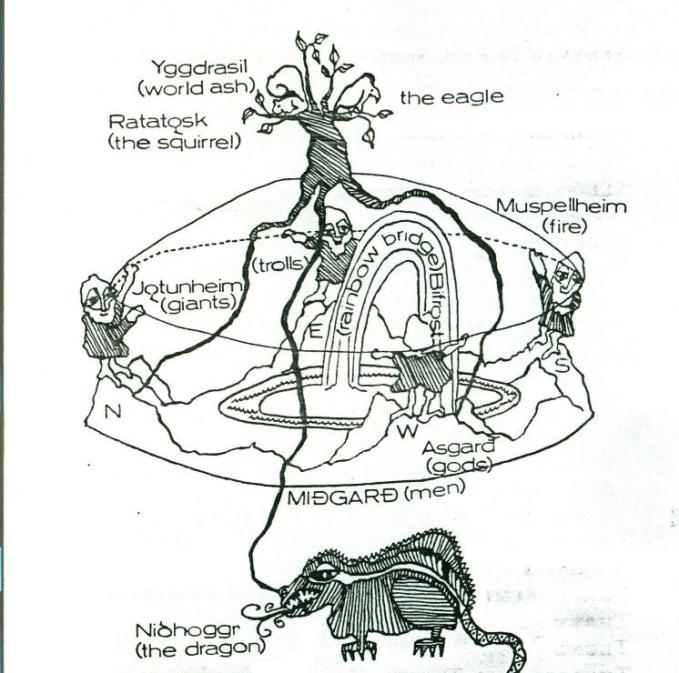

Illustration of Yggdrasil from W. H. Auden and P.B. Taylor's The Elder Edda

It would seem that the people who created the stories (perhaps to

transmit this wisdom to their children and descendants) about the gods and

goddesses could certainly have encoded information about astronomical phenomena.

There do seem to be hidden astronomical references

present in the Norse Myths and there is also evidence that the Norse were

inheritors of this ancient Sumerian/Babylonian tradition and this becomes

clearer when we look at some special numbers found in the mythology.

|

Fimm hundruð dura |

23. Five hundred doors and forty there are, I ween, in Valhall’s walls; Eight hundred fighters through one door fare When to war with the wolf they go. (Henry A. Bellows Translation, 1923) |

540 has the factors 20, a standard numerical

unit known as a score, and 27, which also happens to be a number that is called

the sidereal lunar cycle or the number of days it takes for the moon to return

to the same place in the sky. When you multiply 540 and 800 it ends up

being 432,000 which is an astronomically significant number.

A Chaldean priest named Berossos, who wrote in Greek circa 289 B.C., reported

the Mesopotamian belief that 432,000 years had elapsed between the crowning of

the first earthly king and the coming of the deluge(2). In the Babylonian or

Sumerian story, there were ten kings total who lived very long lives from

creation to the time of the flood which is a total of 432,000 years. This

number represents the number of years in the Babylonian Great Year and the time

it takes for the planets to return to their exact same position in the sky (3).

To discover that this non-arbitrary, ancient Babylonian/Sumerian number used in

their mythology and astronomy is also present in the Norse myths is remarkable.

In the related Biblical account, there were ten patriarchs between Adam and

Noah, who also lived long lives. Noah was 600 years old at the time of the

landing of the Ark on Mount Ararat. The total years add up to 1,656. In 1,656

years, there are 86,400 weeks, and half that number is 43,200. Doubling and

cutting in half these figures seems to be a common theme. The number of years

from Adam to Noah seems to hide the time cycle number and indicates that the

composer of this text and also the composer of the Norse poem had a working

knowledge of the earth’s cycle of precession, which that number indicates.

Precession is the periodic wobble of the earth, which spins like a spinning top.

When the Earth wobbles, it does it over a very long period of time and the

wobble only makes one complete revolution every 25,920 years. This figure

divided by the sexagesimal base number 60 results in the number 432. There is

further evidence that the ancient Norse divided up the heavens into equal slices

of a 360 circular pie, echoing the approach of the Babylonians and Sumerians

with their use of sexagesimal calculations, just like we currently use

sexagesimal instruments such as the watch and clock, along-side standard decimal

mathematics.

|

|

IIt is clear that the Babylonian astronomers

thought in terms of sixes and twelves more than our current culture does, which

is to think in terms of tens, 100’s and thousands. The sexagesimal

calculation, 60 x 60 x 120, equals 432,000. For a 6 and 12-based society,

talking about 432,000 of something is like talking about a hundred thousand of

something to present day people. For a Babylonian astronomer, 432,000 would seem

like a nice, even number since it has multiple factors that are easy sexagesimal

calculations.

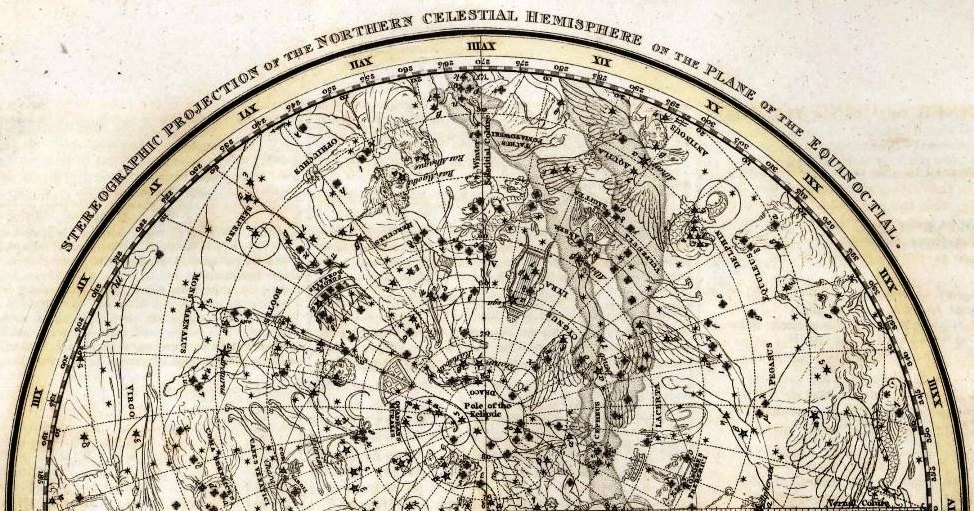

Grímnismál also contains a description of the Norse cosmology and the homes

of the gods. As noted above, this lay contains the astronomically

significant number 432,000, however, an earlier portion of the poem describing

the gods’ homes and lands has sexagesimal influence because twelve homes of the

gods and goddesses are described:

|

1. Thrudheim for Thor as well as Ydalir (the

Yewdales apparently in Thrudheim) for Ull who is his stepson. |

With twelve homes of the gods mentioned, it

can be seen as a hint that they are located in the sky, since the sky has for

many thousands of years been divided up into twelve equal “houses” as they are

known in present day astrology. Homes and houses are the same thing both

in the present and the past.

Here we have ancient Mesopotamian numbers showing up in a Norse poem – that is

very interesting isn’t it? In addition to these numbers, however, there

are some other clues that the poems are describing stellar locations and

heavenly bodies.

In Skáldskaparmál in the Prose Edda, Aurvandill, SIf’s first husband and father

of Ull, is mentioned in the context of a journey he took with the god Thor:

| [Þórr] hafði vaðit norðan yfir Élivága ok hafði borit í meis á baki sér Aurvandil norðan ór Jötunheimum, ok þat til jartegna, at ein tá hans hafði staðit ór meisinum, ok var sú frerin, svá at Þórr braut af ok kastaði upp á himin ok gerði af stjörnu þá, er heitir Aurvandilstá. |

Thor had waded from the north over the river Elivagar and had borne Aurvandill in a basket on his back from the north out of Jotunheim. And he added for a token, that one of Aurvandill's toes had stuck out of the basket, and became frozen; wherefore Thor broke it off and cast it up into the heavens, and made thereof the star called Aurvandill's Toe. |

Norse Aurvandill is the same as the Old

English Ēarendel and has been thought to mean "luminous wanderer", a reasonable

description of the planet Venus, since “planet” means “wanderer.” It would

seem reasonable that the Norse were referring to Venus in the myth where Thor

throws Aurvandill’s toe up into the heavens.

Old English Earendel appears in glosses translating iubar as "radiance” or

“morning star." In the Old English poem Crist I are the lines:

| éala

éarendel engla beorhtast ofer middangeard monnum sended and sodfasta sunnan leoma, tohrt ofer tunglas þu tida gehvane of sylfum þe symle inlihtes. |

Hail Earendel, brightest of angels, |

The name Earendel is here taken to refer to

John the Baptist and he is addressed as the morning star which heralds the

coming of Christ, the sun. Of course, there are other theories, including

Richard Allen’s who links Orion with Aurvandill, identifies the star Rigel as

one of his toes and the frozen and broken-off toe as the star Alcor (5).

There are also direct references to heavenly bodies in Norse Mythology.

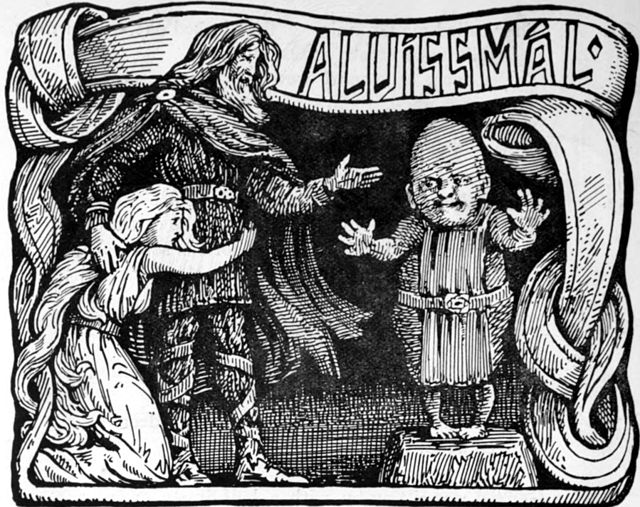

The poem Alvismal contains a series of back and forth questions and answers

about what the heavenly bodies are called by various races. Thor asks

Alvis these questions to test the knowledge of the dwarf who wants to be the

suitor for his daughter Thrud.

|

|

| Illustrations by William Gershom Collingwood (1854-1932) | |

|

Þórr kvað: "Segðu mér þat, Alvíss, |

Thor spake 9. "Answer me, Alvis! thou knowest all, Dwarf, of the doom of men: What call they the earth, that lies before all, In each and every world?" |

|

Alvíss kvað: "Jörð heitir með mönnum, |

Alvis spake: 10. " 'Earth' to men, 'Field' to the gods it is, 'The Ways' is it called by the Wanes; 'Ever Green' by the giants, 'The Grower' by elves, 'The Moist' by the holy ones high." |

|

Þórr kvað: |

Thor

spake: 11. "Answer me, Alvis! thou knowest all, Dwarf, of the doom of men: What call they the heaven, beheld of the high one, In each and every world?" |

|

Alvíss kvað: |

Alvis

spake: 12. " 'Heaven' men call it, 'The Height' the gods, The Wanes 'The Weaver of Winds'; Giants 'The Up-World,' elves 'The Fair-Roof,' The dwarfs 'The Dripping Hall.'" |

|

Þórr kvað: |

Thor

spake: 13. "Answer me, Alvis! thou knowest all, Dwarf, of the doom of men.: What call they the moon, that men behold, In each and every world?" |

|

Alvíss kvað: |

Alvis

spake: 14. "'Moon' with men, 'Flame' the gods among, 'The Wheel' in the house of hell; 'The Goer' the giants, 'The Gleamer' the dwarfs, The elves 'The Teller of Time." |

|

Þórr kvað: |

Thor spake: 15. "Answer me, Alvis! thou knowest all, Dwarf, of the doom of men: What call they the sun, that all men see, In each and every world?"

|

|

Alvíss kvað: |

Alvis

spake: 16. "Men call it 'Sun,' gods 'Orb of the Sun,' 'The Deceiver of Dvalin' the dwarfs; The giants 'The Ever-Bright,' elves 'Fair Wheel,' 'All-Glowing' the sons of the gods." (Henry A. Bellows Translation, 1923) |

Dwarves would have had ample opportunity to

observe the night sky since they turned to stone if exposed to the sunlight.

These kennings are not obvious for the phenomena described and the “code”

revealed by Alvis is one of the few instances in the Norse poems where it is

made clear that knowledge of the sky and stars was present among those who wrote

the myths.

There are

more clues in the Eddic and Skaldic poetry that indicate the ancient Norse were

knowledgeable in astronomy, however, the evidence cited above is that which is

most readily recognizable amongst the various poems that make up the corpus of

what we call Norse Mythology. Many more correspondences can be inferred or

intuited by comparison with Roman, Greek and Indian mythology which have better

preserved the astral connections to the myths and this is a fascinating area of

study which merits a great deal more research.

1. A.

Aaboe (May 2, 1974). "Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity". Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society 276 (1257): 21–42. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0007.

JSTOR 74272.

2. Thorkild Jacobsen, The Sumerian King List, 1939, pp.

71, 77.

3. Ogier, J. Eddic Constellations.

4. Crist I (ll. 104–108) by Cynewulf.

5. Richard Hinckley Allen, Star Names; Their Lore and

Meaning.