Pseudomythological Constellations Maps

ATTEMPT TO RECONSTRUCT FOLK ASTRONOMY

by Andres Kuperjanov

An excerpt from Folklore Vol. 32, 2006

Return to Germanic Astronomy

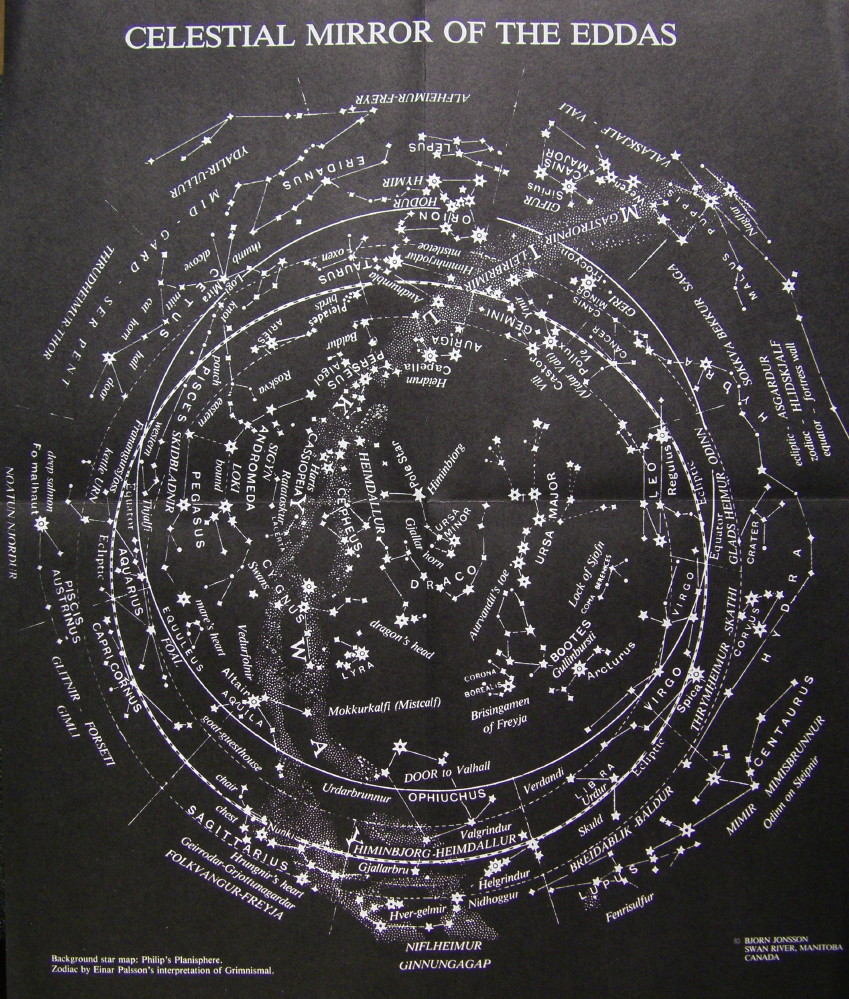

6.1. Star Myths of the Vikings – New Conceptualisation of Nordic Mythology

As far as is known, material recorded about the wisdom of stars among the Scandinavians is relatively scanty. Bjorn Jónsson (1920– 1995), a resident of Canada, aspired to find links between the Old Scandinavian and traditional stellar skies. For this purpose, he selected extracts of possible astronomical content from the works of Snorri Sturluson and used these to build a cosmological system. He published the results in his book Star Myths of the Vikings (Jónsson 1994).

At first, the author claims that Snorri’s Edda (also known as the Younger Edda or the Prose Edda), which dates back to the 13th century, can to some extent be interpreted as a collection of astronomical texts, even though its author, Snorri Sturluson, has not pointed that out, possibly owing to the reason that church officials of the time viewed any knowledge of astronomy as an expression of a pagan mindset. The author also claims that since in the prologue to Snorri’s Edda, Sturluson has referred to the similarity of the Scandinavian polytheist system to that of the antiquities, he has chosen to use the mythological schemes of the Old World in his interpretations.

Considering the knowledge Vikings had in those times, this methodology is perfectly acceptable. It is known that Oddi Helgason, who was called Stjerna Oddi (Star Oddi), developed tables on the basis of his observations (approx. 1100–1150), which enabled to perform calendar calculations, and determine the time of solstices and equinoxes, the divergence from the Julian calendar, weekly height of the sun and the azimuths of sunrise and sunset. Therefore as late as in the 12th century, knowledge of astronomy in Iceland met the general standards of the time and probably corresponded to the knowledge in all of Europe. Secondly, since in the 12th century astronomy was practiced at a high level and was very popular, a scientific description of the world, including a sky map, must have been in use at the time. Thirdly, Vikings had long been known as skilled navigators. Their shipways reached deep into ancient areas and navigation was based on good knowledge of the stellar sky. It is likely that astronomy proper reached the Viking world considerably earlier than in the specified 12th century. Therefore, it is very likely that a traditional sky map could have been used in these regions in the 13th century (and, of course, much earlier), on the basis of which constellations had been named/interpreted according to a given mythology and then supported with a corresponding narrative to simplify orientation. A similar transformation of ‘foreign’ knowledge into ‘own’ has been noted in many other areas of folk knowledge.

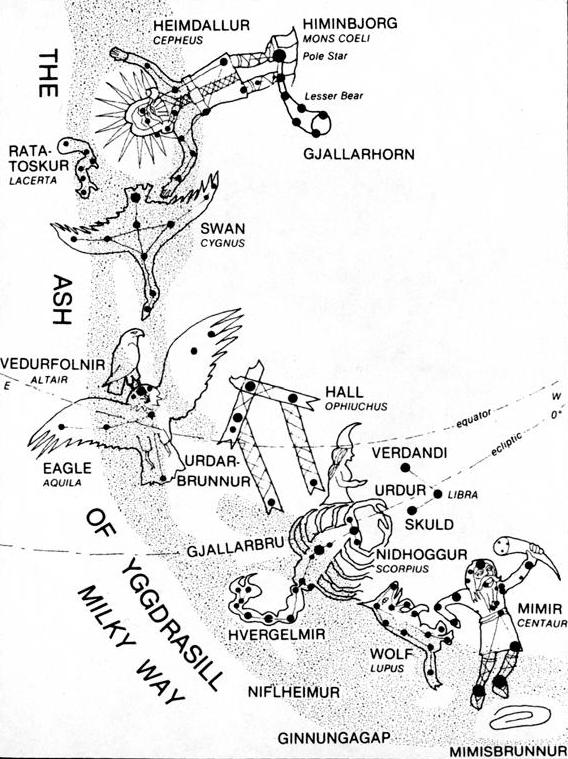

Bjorn Jónsson has started with interpreting constellations in the Milky Way area, which owing to its peculiarity can be used as a key. The Milky Way represents, of course, the world tree Yggdrasill. It is very difficult to ascribe the interpretation of this area of sky to any particular nation. The concept of the world tree and the birds that live on its branches and the snake on its roots are highly universal motifs. It has been thought that visually the Milky Way is more similar to a tree especially in Northern areas – Heino Eelsalu suggests that the concept of an association between the world tree and the Milky Way could have emerged about six thousand years ago at latitudes 30–40 degrees North (Eelsalu 1985: 69) – at lower latitudes, the association with a pathway or a river is more common, whereas the latter is almost never mentioned in the north. Therefore identifying the large ash tree Yggdrasill with the Milky Way is a logical solution for Scandinavian regions. The Milky Way is observed far into the south. This is highly likely considering that the Vikings also travelled in the Mediterranean area. The interpretation of some constellations on the Milky Way (Swan, Eagle, Ratatosk [constellation of Squirrel (Lizard)], Snake) is also likely, and the rest may already be too hypothetical.

The ecliptic is important in the cosmological sense; the abode of the gods is above the ecliptic and the underworld inhabited by monsters and the dead is below. Applying this principle and proceeding from the world tree (the giant ash tree Yggdrasill), Bjorn Jónsson has started to associate the text of Edda with the sky map. The result of the interpretation is of course arguable, but in principle, such an approach is justified. The result is a unique version of the traditional sky map, which even in those days was probably largely an artificial creation. If such a representation of the sky (sky map) did exist and was widely used, then this could have wiped out earlier truly folk astronomical knowledge of the sky. But because it is relatively new and nonauthentic (folk) astronomy, then it was not preserved and was entirely replaced by the classical sky map in the course of later ideological attacks. And this also yields the hypothetical explanation why so little folk astronomical material has been preserved in Scandinavia.

Björn Jónsson's