And the Guardians of the Netherworld

by Peter Krüger

©2013

[Germanic Astronomy]

We have seen

in the essay

Scorpio and the Hound of Hel

that the constellation Scorpio appears in Greek astral

mythology also as Cerberus, the hound of hel, and in Eddic sources as Garm or

Fenrir. One of the major keys to a identification has been the story preserved

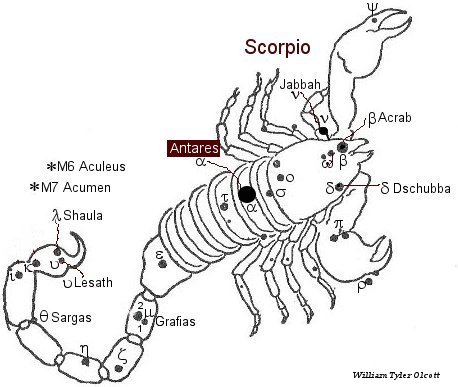

in Baldrs draumar about a whelp with a bloody breast. The bloody breast can be

paralleled to the red super-giant star Antares known in Greek also as Kardia

Scorpiu, in Latin Cor Scorpii, the heart of the Scorpion. In the

cuneiform tablet MUL.APIN Antares is called GABA.GIR.TAB, the breast of the

scorpion.

|

|

In the following essay I want to show that the star Antares is also key for a better understanding of different obscure female giantesses like Hyndla, Vala, Modgud, Hyrrokkin and Thokk. A connection to the hirtir ['herder'] of Skirnismal and Thakkrad in Volundarkvida seems also to be possible.

In Sumerian tradition Antares was not only seen as GABA.GIR.TAB, the breast of the scorpion but also as a deity called Lisi. The star was originally representing a goddess who was later redefined as a male god. Lisi was closely related to fire and the brazier, the cuneiform name was written with the signs for brazier and red. The male god’s name bears epithets like ‘he who burns with fire’ and ‘he who burns an offering’. It is also very interesting that the name Lisi was used as a generic title for ‘lamenting goddesses’ (compare Gavin White, Babylonian Star-lore).

Let us compare these descriptions with different Eddic tales.

|

|

|

BALDUR'S DREAMS

The Bloody Whelp and the Völva

In the poem Baldrs draumar Odin is riding on Sleipnir to Niflhel (the Milky Way in the region of Sagittarius, Scorpius and especially Sagitta; compare German ‘Sternennebel’ for diffuse star areas). He meets a whelp with a bloody breast (Scorpio as the hellhound, the bloody breast referring to Antares), coming from a cave (þeim er ór helju koma). This has a parallel to Garm in the Gnipahellir in Völuspá.

As Odin rides, the ground rattles (foldvegr dunði). We find a similar description in Gylfaginning 49 when Hermod crosses the Gjallarbru. He alone makes more noise than five troops of deadmen who passed before him.

On his way to Niflhel, Odin stops east of the gate (‘dyrr’, i.e. the constellation Ophiuchus seen as a door) at the grave of a völva. I assume that this is a reference to the giantess represented by the bright red star Antares. Odin awakes the völva who says that she has been covered with snow, beaten by rain and moistened with dew. This is a hint to her location at the Milky Way, seen as a misty mountain area. Interestingly in Sumerian star lore, in this area of heaven there was also a Sacred Mound, which was a grave mound covering a passageway to the underworld.

Odin asks the völva several things about the fate of Baldur. Very interesting is his final question where he asks ‘who are the maidens that weep at will and cast their neck-veils heavenward’. This question might be closely related to the Sumerian story about Lisi and the ‘lamenting goddesses’.

HYNDLULJÓÞ

Hyndluljóð

describes how Freyja meets a giantess called Hyndla. The name Hyndla itself

means ‘little dog’, reminiscent of the whelp in Baldrs draumar. In addition

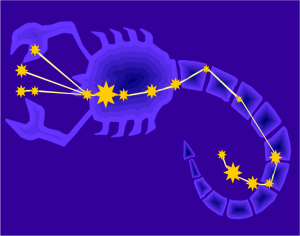

Hyndla rides on a wolf. If we look on the shape of the constellation Scorpio, it

is easy to imagine that the star Antares is seen as ‘riding’ on the other stars

of Scorpio. It seems that the whole constellation of Scorpio was seen as the

hell hound and the cardinal star Antares also as a whelp.

|

Hyndla is said to live in a cave (‘er

i helli byr’).

This is reminiscent of the Gnipahellir where the hellhound Garmr is

lives and, in Baldrs draumr, of the whelp coming from Hel (‘þeim er

ór helju koma’).

In

Hyndluljóð, Freyja is said to be on the valsinni, ['the way of

the slain']. The valsinni is probably comparable to the

helveg mentioned in Gylfaginning 49, the road to Hel, the zodiac

crossing the Milky Way at Scorpio or the Milky Way itself.

|

The mission of Freyja is to find out the pedigree of her husband Ottar. Why is Hyndla the right person to ask?

As Antares/Hyndla is located on the Hel-way, all

dead men must pass her so she knows all of their names as well as their

ancestry.

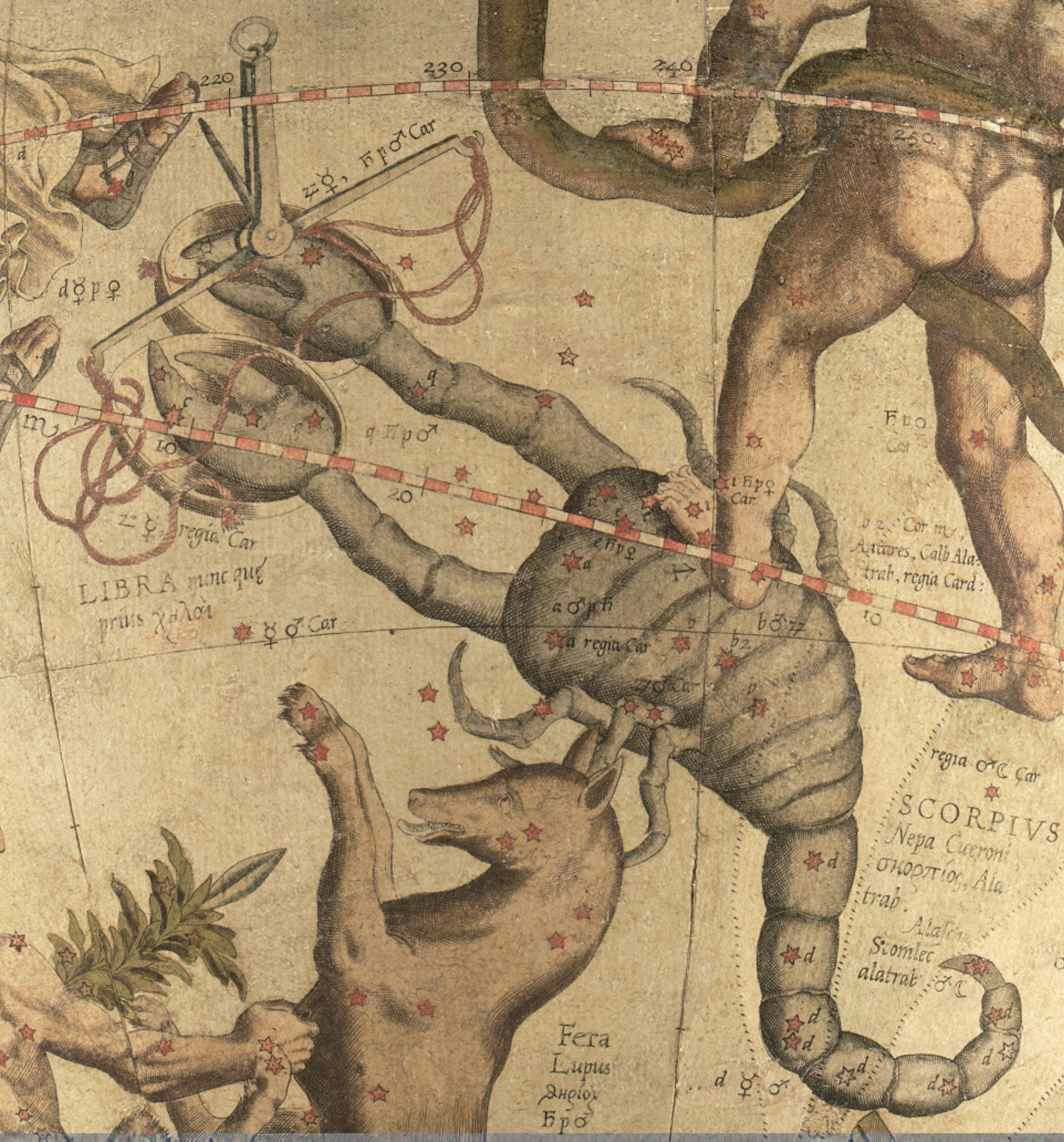

Gylfaginning 49: Hermod’s Journey to Hel

We find

another related story in Gylfaginning 49. After the death of Balder,

Hermodr is dispatched to Hel on the Hel-way (the zodiac). He rides through dark

and deep dales till he arrives at the river Gjallar (the constellation Scorpio

here seen as a river). The river has to be crossed at the bridge Gjallarbrú

attended by a guardian called Modgudr (the star Antares). The bridge thunders

beneath him (‘dynr’, compare the rattling earth in Baldrs draumar).

Modgudr asked him about his name and race (compare to Hyndla). Interesting, she

says that he doesn't have the color of a dead man. Upon arriving at the

hell-gate (‘helgrindum’, compare to the ‘dyrr’ of Baldrs draumar,

Ophiuchus) Hermodr then takes the helveg ("en

niðr ok norðr liggr helvegr.")

Gylfaginning 49: Thökk & Hyrrokkin

Hel told Hermodr

that Baldur would be released if the whole of creation wept for him. However, a

giantess (gýgr) in a cave (‘í helli’, compare the Gnipahellir)

called Thökk (the name might be related to Thakkrad in Völundarkvida) refused to

weep. I assume Thökk acts here as a guardian of the netherworld, who like the

Greek Cerberus, refuses to let people escape from the realm of the dead.

In another story related to Baldur's funeral appears a giantess called Hyrrokkin riding like Hyndla on a wolf (vargi). Her name is normally translated as ‘fire-smoked’ and reminds one of the cuneiform sign of the Sumerian goddess Lisi and Antares, depicting a brazier. Like the other figures discussed above, she is associated with a shaking of the earth:

‘Hyrrokkin then went to the ship, and with a single push set it

afloat, but the motion was so violent that the fire sparkled from the

rollers, and the earth shook all around

('ok lönd öll skulfu’).

This shaking of the earth, we also find in connection to the bound Loki

(Ophiuchus) and ‘earthquakes’.

|

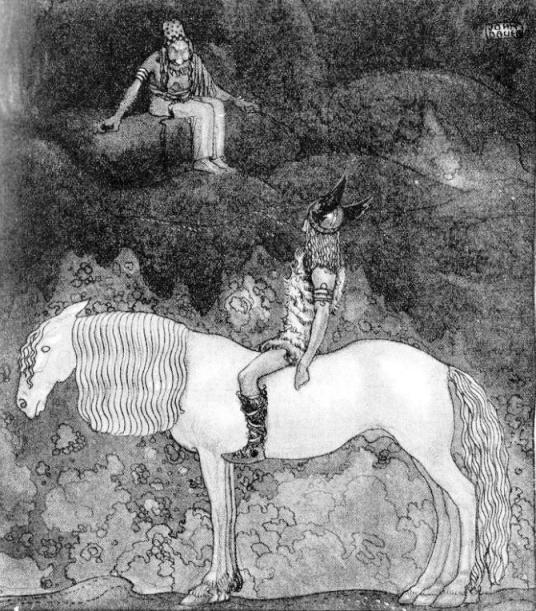

Skírnismál

In Skírnismál, we also find parallels to the stories mentioned above . Skirnir is riding on a horse through moistened mountains (Milky Way). He meets a guardian (hirðir, Antares) sitting ‘á haugi’ ['on the gravemound'], hounds are howling (Scorpio, the hellhound, perhaps in this poem seen with multiple heads like Cerberus). The guardian asks him if he is already dead showing that he is indeed the guardian of the netherworld (compare the remark of Modgudr). Gerd mentions loud noises in front of her house (‘skjalfa gardar Gymis’, like the rattling of the earth and the thundering bridge).

Interestingly the guardian seems to watch several ways ‘ok varðar alla vega’. What might this mean? Besides laying on the Milky Way and the zodiac, at one time, Antares was also seen as the point at which the zodiac crossed the celestial equator (around 3050 BC), however, because of precession, this point is shifting. This story might thus be an echo of its role as guardian of three ways.

|

Overall we

find in different stories hints to a guardian or seeress represented by the

bright red star Antares. In Old Persian traditions, there have been four

guardians of the heavens, also called the four royal stars. They consist of

Aldebaran in Taurus, Antares in Scorpius, Regulus in Leo and

Formalhaut in Piscis Australis together marking

the four cardinal points of the year: the equinoxes and solstices. In the

stories, Antares seems to represent the winter solstice, the time of the dead,

and might explain the role of such obscure figures as the Völva, Hyndla, Modgud,

Thökk, Thakkrad, Hyrrokkin and the unnamed herdsman of Skírnismál.